Search results

122 results found.

122 results found.

Wisconsin Reading Coalition:

A new report has been released by the National Council on Teacher Quality: Learning About Learning: What Every New Teacher Needs to Know. In terms of instructional strategies that help students learn and retain new concepts, a lot was found missing from textbooks currently used to train teachers.

The Learning Difference Network of Dane County has formed an online discussion group for parents of children with dyslexia and other related learning differences. To join, click the following link, log into Facebook, and when group page opens, click the box “Join Group” – the administrator will get your request and approve your membership within 24 hours. https://www.facebook.com/groups/LDNParentGroup/

Congratulations to the Children’s Dyslexia Center-Madison on opening four new classrooms! The expansion was made possible by the Scottish Rite Masons and the Madison community.

The National Council on Teacher Quality has unveiled Path to Teach, an online website billed as a consumer’s guide to colleges of education.

Teacher-candidates-to-be can look up college programs and alternative programs from across the nation, comparing them by tuition costs, enrollment numbers, location, and by a quality snapshot that looks at criteria like admissions selectivity, preparation to teach in different content areas, and student-teaching quality.

Path to Teach’s A-F grades are based on the NCTQ’s project to assess elementary, secondary, and special education programs in every education school. The rankings are often fairly unsparing (“This program will not prepare you to teach young children to read,” says the typical warning for an F grade for early reading.)

Wisconsin Reading Coalition, via a kind email:

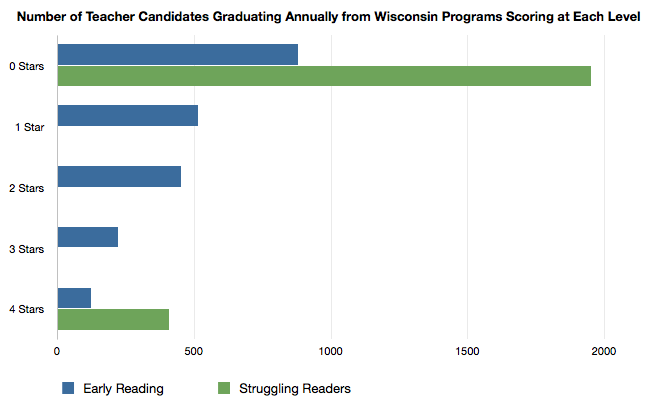

The National Council on Teacher Quality has released its second annual report on teacher preparation programs, including a numeric ranking of programs for the first time. Results show an uphill climb ahead for Wisconsin.

No Wisconsin program earned the national “Top-Ranked” status, a distinction awarded to 107 programs in the nation.Wisconsin is one of 17 states and the District of Columbia that had no Top-Ranked programs.

UW-Eau Claire has the highest ranked elementary program in Wisconsin.

22 programs in Wisconsin were in the bottom half of the national sample, and therefore were not ranked.14 programs (9 elementary and 5 secondary) were in the top half and received a ranking.

Only 1 in 4 programs prepared teachers in effective scientifically-based reading instruction.Alverno College, Edgewood College, Lakeland College, Lawrence University, Maranatha Baptist Bible College, St. Norbert College, Viterbo University, and Wisconsin Lutheran College did not cooperate in the review.

Read the report specifics here.

Report questions quality of UW System education schools.

National Council on Teacher Quality (PDF):

1. The state should require teacher candidates to pass a test of academic proficiency that assesses reading, writing and mathematics skills as a criterion for admission to teacher preparation programs.

2. All preparation programs in a state should use a common admissions test to facilitate program comparison, and the test should allow comparison of applicants to the general college-going population. The selection of applicants should be limited to the top half of that population.

Wisconsin requires that approved undergraduate teacher preparation programs only accept teacher can- didates who have passed a basic skills test, the Praxis I. Although the state sets the minimum score for this test, it is normed just to the prospective teacher population. The state also allows teacher preparation programs to exempt candidates who demonstrate equivalent performance on a college entrance exam.

Wisconsin also requires a 2.5 GPA for admission to an undergraduate program.

To promote diversity, Wisconsin allows programs to admit up to 10 percent of the total number of students admitted who have not passed the basic skills test.

RECOMMENDATION

Require all teacher candidates to pass a test of academic proficiency that assesses reading, writing and mathematics skills as a criterion for admission to teacher preparation programs.

Even though the state’s policy that permits programs to admit up to 10 percent of students who have not passed the basic skills test is part of a laudable goal to promote diversity, allowing this exemption is risky because of the low bar set by the Praxis I (see next recommendation).

Require preparation programs to use a common test normed to the general college-bound population.

Wisconsin should require an assessment that demonstrates that candidates are academically com- petitive with all peers, regardless of their intended profession. Requiring a common test normed to the general college population would allow for the selection of applicants in the top half of their class, as well as facilitate program comparison.

Consider requiring candidates to pass subject-matter tests as a condition of admission into teacher programs.

In addition to ensuring that programs require a measure of academic performance for admission, Wisconsin might also want to consider requiring content testing prior to program admission as opposed to at the point of program completion. Program candidates are likely to have completed coursework that covers related test content in the prerequisite classes required for program admis- sion. Thus, it would be sensible to have candidates take content tests while this knowledge is fresh rather than wait two years to fulfill the requirement, and candidates lacking sufficient expertise would be able to remedy deficits prior to entering formal preparation.

For admission to teacher preparation programs, Rhode Island and Delaware require a test of academic proficiency normed to the general college- bound population rather than a test that is normed just to prospective teachers. Delaware also requires teacher candidates to have a 3.0 GPA or be in the top 50th percentile for general education coursework completed. Rhode Island also requires an average cohort GPA of 3.0, and beginning in 2016, the cohort mean score on nationally-normed tests such as the ACT, SAT or GRE must be in the top 50th percentile. In 2020, the requirement for the mean test score will increase from the top half to the top third.

via a kind Wisconsin Reading Coalition email:

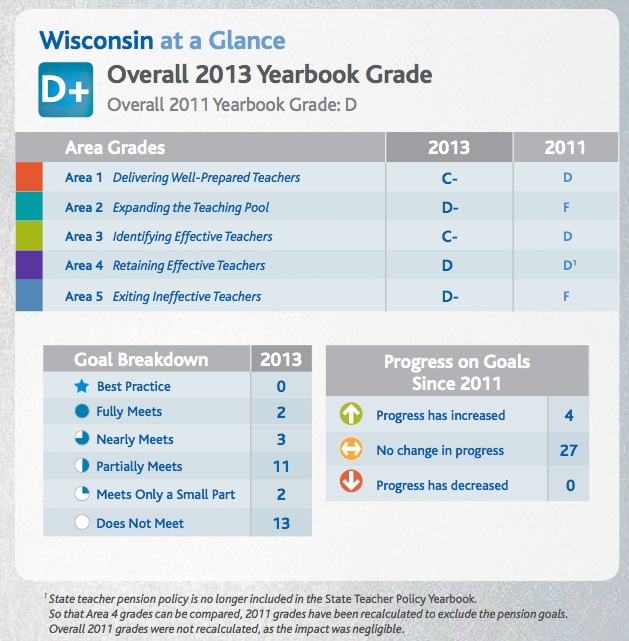

After receiving a grade of D in 2009 and 2001, Wisconsin has risen to a D+ on the 2013 State Teacher Policy Yearbook released by the National Council on Teacher Quality.

In the area of producing effective teachers of reading, Wisconsin received a bump up for requiring a rigorous test on the science of reading. The Foundations of Reading exam will be required beginning January 31, 2014.

Ironically, Wisconsin also scored low for not requiring teacher preparation programs to prepare candidates in the science of reading instruction. We hope that will change through the revision of the content guidelines related to elementary licensure during a comprehensive review process that is underway at DPI this winter and spring.

Teaching was once dubbed “the profession that eats its young” and many educators liken their first few years in the classroom to a hazing ritual. The result is an industry that hemorrhages new teachers nearly as fast as it can license them.

One factor feeding the high turnover rate is lack of preparation, according to Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, a national union representing 1.5 million educators.

“Newly minted teachers are tossed the keys to their classrooms … and left to see if they (and their students) sink or swim,” she wrote in a December 2012 report for the AFT. The report called for higher standards and accountability in teacher training programs.

The 2013 NCTQ Teacher Prep Ratings, released today by U.S. News, are a step in that direction.

[Read U.S. News Editor Brian Kelly’s opinion on the NCTQ ratings.]

Part of a broader effort by the National Council on Teacher Quality, the ratings are a subset of the NCTQ Teacher Prep Review, published today by the nonprofit educational research and advocacy group. The review is a 2.5-year effort to gauge the quality of the bachelor’s and master’s degree tracks required to enter the teaching profession.

But, given that NCTQ has just come out with their really, really big new ratings of teacher preparation institutions… with their primary objective of declaring teacher prep by traditional colleges and universities in the U.S. a massive failure, I figured I should once again revisit why the NCTQ ratings are, in general, methodologically inept & vacuous and more specifically wholly inconsistent with NCTQ’s own primary emphasis that teacher quality and qualifications matter perhaps more than anything else in schools and classrooms.

The debate among scholars and practitioners in education as to whether a good teacher is more important than a good curriculum, or vice versa, is never-ending. Most of us who are engaged in this debate lean one way or the other. Disclosure – I lean in favor of the “good teacher” perspective. Those with labor economics background or interests tend to lean toward the good teacher importance, and perhaps those with more traditional “education” training lean toward the importance of curriculum. I’m grossly oversimplifying here (perhaps opening a can of worms that need not be opened). Clearly, both matter.

I would argue that NCTQ has historically leaned toward the idea that the “good teacher” trumps all – but for their apparent newly acquired love of the Common Core Standards.

Now here’s the thing – if the content area expertise of elementary and secondary classroom teachers and the selectivity and rigor of their preparation matters most of all – how is it that at the college and university level, faculty substantive expertise (including involvement in rigorous research pertaining to the learning sciences, and specifically pertaining to content areas) is completely irrelevant to the quality of institutions that prepare teachers? That just doesn’t make sense.

Much more, here.

National Council on Teacher Quality, via a kind email:

Yesterday, a court in Minnesota delivered a summary judgment ordering the Minnesota State Colleges and University system to deliver the documents for which we asked in our open records (“sunshine”) request for our Teacher Prep Review.

At the heart of our Teacher Prep Review is a simple idea: the more information that aspiring teachers, district and school leaders, teacher educators and the public at large have about the programs producing classroom-ready teachers, the better all teacher training programs will be.

In our effort to produce the first comprehensive review of U.S. teacher prep, we’ve faced a number of challenges — perhaps the most serious of which has been the argument made by some universities that federal copyright law makes it illegal for public institutions publicly approved to prepare public school teachers to make public documents that describe the training they provide.

We want to make sure that everyone understands what this ruling does and does not mean. The Minnesota State colleges and universities system agreed with us that the syllabi we seek are indeed public record documents. Their case came down to the claim that because the course syllabi are also the intellectual property of professors, they should not have to deliver copies of their syllabi to us.

Minnesota’s open records law, the court ruled, is clear: public institutions must make documents accessible to individuals seeking them — which includes delivering copies to them. Delivering copies of these documents to us in no way, shape or form deprives the professors who created them of their intellectual property rights. NCTQ is conducting a research study, which means that our use of these syllabi falls under the fair use provision of the copyright law. This is the exactly the same provision that enables all researchers, including teacher educators, to make copies of key documents they need to analyze to make advances in our collective knowledge.

Related:

Kate Walsh, via a kind reader’s email:

As reported by the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel and the Associated Press, NCTQ filed a lawsuit yesterday — a first for us — against the University of Wisconsin system.

UW campuses issued identically worded denials of our requests for course syllabi, which is one of the many sources of information we use to rate programs for the National Review of teacher preparation programs. They argue that “syllabi are not public records because they are subject to copyright” and therefore do not have to be produced in response to an open records request.

We believe that the University’s reading of the law is flawed. We are engaged in research on the quality of teacher preparation programs, and so our request falls squarely within the fair use provision of copyright law. What’s more, these documents were created at public institutions for the training of public school teachers, and so should be subject to scrutiny by the public.

You can read our complaint here.

Related Georgia, Wisconsin Education Schools Back Out of NCTQ Review

Public higher education institutions in Wisconsin and Georgia–and possibly as many as five other states–will not participate voluntarily in a review of education schools now being conducted by the National Council for Teacher Quality and U.S. News and World Report, according to recent correspondence between state consortia and the two groups.

In response, NCTQ and U.S. News are moving forward with plans to obtain the information from these institutions through open-records requests.

In letters to the two organizations, the president of the University of Wisconsin system and the chancellor of Georgia’s board of regents said their public institutions would opt out of the review, citing a lack of transparency and questionable methodology, among other concerns.

Formally announced in January, the review will rate education schools on up to 18 standards, basing the decisions primarily on examinations of course syllabuses and student-teaching manuals.

Lake Wobegon has nothing on the UW-Madison School of Education. All of the children in Garrison Keillor’s fictional Minnesota town are “above average.” Well, in the School of Education they’re all A students.

The 1,400 or so kids in the teacher-training department soared to a dizzying 3.91 grade point average on a four-point scale in the spring 2009 semester.

This was par for the course, so to speak. The eight departments in Education (see below) had an aggregate 3.69 grade point average, next to Pharmacy the highest among the UW’s schools. Scrolling through the Registrar’s online grade records is a discombobulating experience, if you hold to an old-school belief that average kids get C’s and only the really high performers score A’s.

Much like a modern-day middle school honors assembly, everybody’s a winner at the UW School of Education. In its Department of Curriculum and Instruction (that’s the teacher-training program), 96% of the undergraduates who received letter grades collected A’s and a handful of A/B’s. No fluke, another survey taken 12 years ago found almost exactly the same percentage.

Stephen Sawchuk, via a kind reader’s email:

Public higher education institutions in Wisconsin and Georgia–and possibly as many as five other states–will not participate voluntarily in a review of education schools now being conducted by the National Council for Teacher Quality and U.S. News and World Report, according to recent correspondence between state consortia and the two groups.

In response, NCTQ and U.S. News are moving forward with plans to obtain the information from these institutions through open-records requests.

In letters to the two organizations, the president of the University of Wisconsin system and the chancellor of Georgia’s board of regents said their public institutions would opt out of the review, citing a lack of transparency and questionable methodology, among other concerns.

Formally announced in January, the review will rate education schools on up to 18 standards, basing the decisions primarily on examinations of course syllabuses and student-teaching manuals.

The situation is murkier in New York, Maryland, Colorado, and California, where public university officials have sent letters to NCTQ and U.S. News requesting changes to the review process, but haven’t yet declined to take part willingly.

In Kentucky, the presidents, provosts, and ed. school deans of public universities wrote in a letter to the research and advocacy group and the newsmagazine that they won’t “endorse” the review. It’s not yet clear what that means for their participation.

Lake Wobegon has nothing on the UW-Madison School of Education. All of the children in Garrison Keillor’s fictional Minnesota town are “above average.” Well, in the School of Education they’re all A students.

The 1,400 or so kids in the teacher-training department soared to a dizzying 3.91 grade point average on a four-point scale in the spring 2009 semester.

This was par for the course, so to speak. The eight departments in Education (see below) had an aggregate 3.69 grade point average, next to Pharmacy the highest among the UW’s schools. Scrolling through the Registrar’s online grade records is a discombobulating experience, if you hold to an old-school belief that average kids get C’s and only the really high performers score A’s.

Much like a modern-day middle school honors assembly, everybody’s a winner at the UW School of Education. In its Department of Curriculum and Instruction (that’s the teacher-training program), 96% of the undergraduates who received letter grades collected A’s and a handful of A/B’s. No fluke, another survey taken 12 years ago found almost exactly the same percentage.

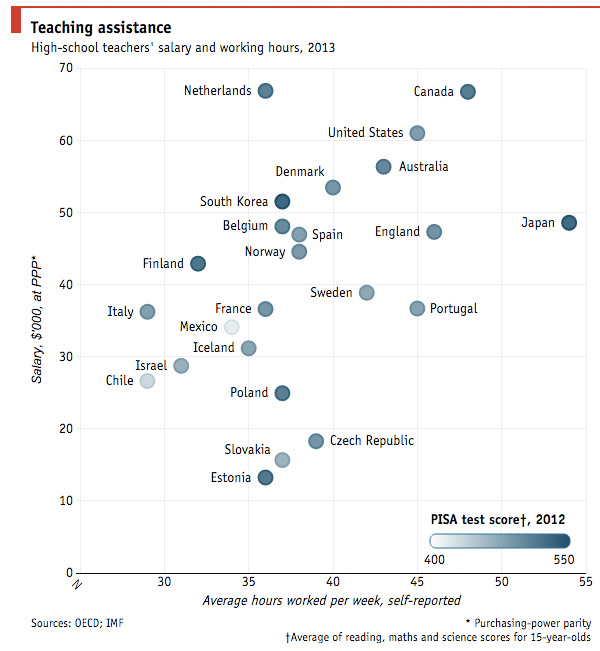

The National Council on Teacher Quality has published their first Square off, where two economists debate: “Are Teachers Underpaid“?

Christopher Peak and Emily Haavik

Pressure is mounting on two universities to change the way they train on-the-job educators to teach reading.

The Ohio State University in Columbus and Lesley University near Boston both run prominent literacy training programs that include a theorycontradicted by decades of cognitive science research. Amid a $660 million effort to retrain teachers that’s underway in 36 states, other academic institutions are updating their professional development. Yet Ohio State and Lesley are resisting criticism and standing by their training.

For decades, their Literacy Collaborative programs deemphasized teaching beginning readers how to sound out words. These programs do cover some phonics, but they also teach that students can use context clues to decipher unfamiliar words. Studies have repeatedly shown that guessing words from context is inefficient, unreliable and counterproductive. Twelve states have effectively banned school districts from using that flawed approach.

The approach, sometimes called “cueing,” originated in the 1960s in the United States and New Zealand, and was popularized in American reading instruction by Gay Su Pinnell and Irene Fountas, professors at the two universities. Pinnell, who is now retired, founded OSU’s Literacy Collaborative, and Fountas founded and still directs Lesley’s Center for Reading Recovery & Literacy Collaborative.

—-

Jenny Warner shares:

As if they took a cue from @FountasPinnell, @OhioState won’t speak publicly, lucky for us @lesley_u took their cue from Calkins and shared their adoration for @rrcna_org and how they haven’t altered how they teach future teachers how to read, but rather how teach them to be “politically savvy.”

—

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

As district administrators know, there’s no one way to map the school calendar. Depending on where you live, the start of the school year may be set to coincide with the dog days of summer or the onset of fall. Across the districts in NCTQ’s Teacher Contract Database (TCD), there are 39 days between when the earliest and latest school years begin. While the range of starting dates is interesting, what may be of more consequence, given the connection between learning time and outcomes, is that the length of the school year can vary by as many as 17 days for students, and there can be up to a 20-day difference in the number of teacher workdays (days on the job without students) throughout the year.

To further explore the makeup of academic years, this District Trendline looks at the 2023-2024 calendar for 146 of the largest school districts in the United States to provide a snapshot of what the school year looks like for both teachers and students.

Before getting to the details, it’s important to define three categories of days for teachers:

NCTQ:

State education leaders across the country are rightly prioritizing efforts to improve elementary student reading outcomes. However, too often these initiatives do not focus enough on the key component to strong implementation and long-term sustainability: effective teachers. Only when state leaders implement a literacy strategy that prioritizes teacher effectiveness will states achieve a teacher workforce that can strengthen student literacy year after year. This report outlines five policy actions states can take to ensure a well-prepared teacher workforce that can implement and sustain the science of reading in classrooms across the country.

The Challenge

There are 1.3 million children who enter fourth grade each year unable to read at a basic level—that’s nearly 40% of all fourth graders across the country.1 These students may not be able to identify details from a text, sequence events from a story, and—in some cases—may not be able to read the words themselves.2 The rate of students who cannot read at a basic level by fourth grade climbs even higher for students of color, those with learning differences, and those who grow up in low-income households, perpetuating disparate life outcomes.3

——

Wisconsin Recommendations:

Recommendations for Wisconsin

Teacher prep standards:

- Create specific, detailed standards for teacher preparation programs for the five components of reading aligned with the science of reading, including what they should not teach.

- Revise teacher prep reading standards to include the knowledge and skills teachers need to support struggling students, including students with dyslexia, in learning how to read.

- Revise teacher prep reading standards to include the knowledge and skills teachers need to support English Learners in learning how to read.

Legislation and Reading: The Wisconsin Experience 2004-

AN17:

Southeastern Louisiana University’s undergraduate teacher preparation program has been recognized by the National Council on Teacher Quality. The program received a grade of ‘A’ in NCTQ’s new report “Teacher Prep Review: Strengthening Elementary Reading Instruction” for its rigorous preparation of future teachers in how to teach reading.

Southeastern’s program is among just 23 percent nationwide to earn an ‘A’ for meeting standards set by literacy experts for coverage of the most effective methods of reading instruction – often called the “science of reading.”

In order to earn an ‘A,” programs needed to meet a standard of adequate coverage, determined in consultation with literacy experts, for all five core components of scientifically based reading instruction – phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension, and teach fewer than four practices that have been found to inhibit students’ reading progress.

But data shows that most teacher education programs at colleges and universities are still not fully teaching the science of reading.

Instead of learning how to read through pictures, word cues and memorization, children will be taught using a phonics-based method that focuses on sounding out letters and phrases, with the hope of addressing the state’s lagging reading scores.

Wisconsin’s new reading law doesn’t explicitly tell the universities how to teach. But it will prohibit the Department of Public Instruction from approving teacher education programs unless they include science-based early literacy instruction and do not incorporate three-cueing — a model that emphasizes that skilled reading should include using meaning and sentence structure cues to read new words.

Wisconsin teachers who do not receive this training will not be eligible for a license beginning July 1, 2026.

“I do believe that the universities have been one of the major causes of the problems we see in reading,” said State Rep. Joel Kitchens, R- Sturgeon Bay, one of the lead authors on the reading legislation. “They now seem to be moving in the right direction, but change is hard.”

More.

“Well, it’s kind of too bad that we’ve got the smartest people at our universities, and yet we have to create a law to tell them how to teach.”

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

In the long-running reading wars, proponents of phonics have won.

States across the country, both liberal and conservative, are passing laws designed to change the way students are taught to read in a way that is more aligned with the science of reading.

States, schools of education, districts, and — ultimately, the hope is — teachers, are placing a greater emphasis on phonics. Meanwhile, the “three-cueing” method, which encourages students to guess words based on context, has been marginalized. It’s been a striking and swift change.

But there has been much less attention paid to another critical component of reading: background knowledge. A significant body of research suggests students are better able to comprehend what they read when they start with some understanding of the topic they’re reading about. This has led some academics, educators, and journalists to call for intentional efforts to build young children’s knowledge in important areas like science and social studies. Some school districts and teachers have begun integrating this into reading instruction.

Yet new state reading laws have almost entirely omitted attention to this issue, according to a recent review. In other words, building background knowledge is an idea supported by science that has not fully caught on to the science of reading movement. That suggests that while new reading laws might have real benefits, they may fall short of their potential to improve how children are taught to read.

“It’s an underutilized component,” said Dan Trujillo, an administrator and former teacher in the San Marcos Unified School District in California. “There’s a lot of research about that: The more a reader brings into a text, the more advanced their comprehension will be.”

“The radicalism that the left has taken to try to force socialism and Marxism in our classrooms is the most outrageous thing this country has ever seen,” said Ryan Walters, Oklahoma’s superintendent of public instruction. “You all are on the front lines of it.”

As hours-long protests continued outside, the 600-plus member crowd inside was energized, including at this lunchtime gathering in the Marriott ballroom — the only session outside the presidential speeches to which The Inquirer was granted access Friday, with other workshops closed to media. (Topics included: “Comprehensive Sex Education: Sex Ed or Sexualization,” “Dark Money’s Infiltration in Education — and How to Fight It,” and “Driving the Narrative: If You Aren’t Telling the Story, Someone Else Is.”)

This session, which followed remarks from former South Carolina Gov. Nikki Haley, included a panel of education officials — Florida Education Commissioner Manny Diaz Jr., Arkansas Education Secretary Jacob Oliva, and South Carolina Superintendent Ellen Weaver — who touched on some of the big challenges in education, including pandemic learning loss and a reckoning over reading instruction, which many experts say schools have been teaching improperly.

Thirty-eight percent of teacher-education programs are failing to prepare future teachers to teach reading using the most effective methods, according to a new report by the National Council on Teacher Quality, writes Kate Rix on The 74. Fifty-one percent of programs earned an “F” or “D,” while 23 percent received an “A.”

Teaching reading is the top priority in the early grades. As districts and states shift to what’s called the “science of reading,” many veteran teachers — trained to use “balanced literacy” or “whole language” methods that don’t work very well — need to retraining. You’d think the new teachers would be prepared, but many ed schools are slow to change.

Teachers need to understand how to teach phonemic awareness (hearing and manipulating sounds in words), phonics (matching sounds with letters), fluency (reading without much effort), vocabulary and comprehension, says NCTQ. Most teacher-prep programs don’t cover all five adequately: Phonemic awareness is the most neglected.

Readers alarmed by your coverage of a report asserting that Massachusetts is “among the worst states … for preparing teachers how to teach children to read in scientifically proven ways” should be aware that the National Council on Teacher Quality, which issued the report, is a political advocacy group founded by the right-wing Thomas B. Fordham Institute (“Colleges earn low grades on preparing reading teachers,” Page A1, June 14).

Some have understandably objected to the basis for the council’s claims about what prospective teachers are actually being taught in education programs. But the problem here runs deeper. The “science of reading” campaign — with references to “evidence-based” methods — represents a distortion of the data. Many experts have objected to the claim that children must receive explicit phonics instruction in order to learn to read. In fact, that approach, particularly when imposed too early or for too long, can adversely affect children’s depth of understanding (their comprehension of meaning) as well as their enjoyment of reading.

All children deserve to learn to read, and all teachers deserve the preparation and support that will allow them to help their students achieve this goal. Yet more than one-third of fourth graders—1.3 million children1 in the U.S.—cannot read at a basic level.2

Not learning how to read has lifelong consequences. Students who are not reading at grade level by the time they reach fourth grade are four times more likely to drop out of high school,3 which in turn leads to additional challenges for them as adults: lower lifetime earnings,4 higher rates of unemployment,5and a higher likelihood of entering the criminal justice system.6 Even more alarming, the rate of students who cannot read proficiently by fourth grade climbs even higher for students of color, those with learning differences, and those who grow up in low-income households, perpetuating disparate life outcomes.7 This dismal data has nothing to do with the students and everything to do with inequities in access to effective literacy instruction.

The status quo is far from inevitable. In fact, we know the solution to this reading crisis, but we are not using the solution at scale. More than 50 years of research provides a clear picture of effective literacy instruction. These strategies and methods—collectively called scientifically based reading instruction, which is grounded in the science of reading—could dramatically reduce the rate of reading failure. Past estimates have found that while three in 10 children struggle to read (and that rate has grown higher since the pandemic), research indicates that more than 90% of all students could learn to read if they had access to teachers who employed scientifically based reading instruction.8

“Well, it’s kind of too bad that we’ve got the smartest people at our universities, and yet we have to create a law to tell them how to teach.”

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Where is the humility? Where is the institutional courage to admit mistakes and move forward?

Individuals in leadership positions often derive their credibility from being the most knowledgeable person in the room, the unquestioned oracles of knowledge. This moment in education, however, requires leaders who will publicly position themselves as the best learners, not the best knowers. The sector has to reacquaint itself with the science of reading, unlearn some habits, suspend beliefs, and be vulnerable enough to embrace the inevitable learning curve. It will take grace and humility.

The NAACP considers reading proficiency to be a civil rights issue because The Information Age requires literacy to participate fully in a society that pushes nonreaders, systematically, to its margins. Given this, the education sector’s willingness to ignore the neuroscience and research consensus about literacy instruction is worth examining. What allows universities to have internal debates about science and methods that have long been settled? Why would dyslexia receive scant attention in an American credentialing program? Why would thousands of K-12 systems continue to use curricula that, even the authors now acknowledge, must be revised to address deficiencies in core elements of literacy instruction? And why would K-12 systems ignore mountains of evidence showing that foundational reading skills are undertaught?

The same universities who claim to be leading research institutions are eerily silent about their failure to apply the research in preparing teaching candidates. Likewise, the K-12 institutions with mission statements citing equity have systematically created a resource gap where those without money to overcome inadequate instruction are consigned to the margins of society while their better-resourced peers seek tutors or more appropriate school placements. Rather than address these issues, we have focused on untangling America’s racial quagmire – as if these things are mutually exclusive. We seem oblivious to the impact race and class have on our tolerance for student failure and our willingness to promote external control narratives that undermine collective teacher efficacy and obfuscate the central issues: we have not provided direct, systematic, explicit instruction to teach reading; neither curricula nor materials have been evidence-based; professional development dollars have not been used well; assessment has been misunderstood and abused; interventions haven’t been timely; and the dearth of humility from leaders and institutions have limited the possibility of effective change management.

NCTQ:

Among the four core subjects, the greatest number of test takers pass the mathematics subtest, both on the first-attempt—the focus of this brief—and after multiple attempts (the “best-attempt” pass rate).2 This is surprising, perhaps, given the familiar anecdotes documenting elementary teachers’ math anxiety.

Low performance in social studies cannot be definitively explained, but NCTQ has documented the history and geography coursework taken by prospective teachers, finding little evidence that prospective teachers must take courses that are relevant to the social studies (and science) that is on these tests or that is taught in elementary grades.3

Note that Wisconsin data is “forthcoming”…

Related: Wisconsin Foundations of Reading elementary teacher content knowledge exam and Governor Evers extensive use of teacher mulligans.

National Council on teacher quality:

The quality of the teacher workforce is especially important in the early grades, when teachers bear an extraordinary responsibility, building a solid foundation for students in both the knowledge and skills they will need to succeed in later grades, as well as in their future lives.

The past year and a half has laid bare the tremendous challenges teachers face and the essential role they play in supporting students. As the pandemic abates and we reckon with the damage it wrought, we must acknowledge that recovery places unprecedented demands on our education system and its teachers.

Bringing in new teachers who are up to the task requires an understanding of the points along the pathway when we are most likely to lose teaching talent, especially those points at which aspiring teachers of color are lost to the profession.

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

Only 45 percent of would-be elementary teachers pass state licensing tests on the first try in states with strong testing systems concludes a new report by the National Council on Teacher Quality. Twenty-two percent of those who fail — 30 percent of test takers of color — never try again, reports Driven by Data: Using Licensure Tests to Build a Strong, Diverse Teacher Workforce.

Exam takers have the hardest time with tests of content knowledge, such as English language arts, mathematics, science and social studies.

Research shows that “teachers’ test performance predicts their classroom performance,” the report states.

NCTQ found huge variation in the first-time pass rates in different teacher education programs. In some cases, less-selective, more-diverse programs outperformed programs with more advantaged students. Examples are Western Kentucky University, Texas A&M International and Western Connecticut State University.

California, which refused to provide data for the NCTQ study, will allow teacher candidates to skip basic skills and subject-matter tests, if they pass relevant college classes with a B or better, reports Diana Lambert for EdSource.

The California Basic Skills Test (CBEST) measures reading, writing and math skills normally learned in middle school or early in high school. The California Subject Matter Exams for Teachers (CSET) tests proficiency in the subject the prospective teacher will teach, Lambert writes.

Curiously, the Wisconsin State Journal backed Jill Underly for state education superintendent, despite her interest in killing our one teacher content knowledge exam: Foundations of Reading. Wisconsin students now trail Mississippi, a stare that spends less and has fewer teachers per pupil.

Foundations of reading results. 2020 update.

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Assembly against private school forced closure

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

Where is the humility? Where is the institutional courage to admit mistakes and move forward?

Individuals in leadership positions often derive their credibility from being the most knowledgeable person in the room, the unquestioned oracles of knowledge. This moment in education, however, requires leaders who will publicly position themselves as the best learners, not the best knowers. The sector has to reacquaint itself with the science of reading, unlearn some habits, suspend beliefs, and be vulnerable enough to embrace the inevitable learning curve. It will take grace and humility.

The NAACP considers reading proficiency to be a civil rights issue because The Information Age requires literacy to participate fully in a society that pushes nonreaders, systematically, to its margins. Given this, the education sector’s willingness to ignore the neuroscience and research consensus about literacy instruction is worth examining. What allows universities to have internal debates about science and methods that have long been settled? Why would dyslexia receive scant attention in an American credentialing program? Why would thousands of K-12 systems continue to use curricula that, even the authors now acknowledge, must be revised to address deficiencies in core elements of literacy instruction? And why would K-12 systems ignore mountains of evidence showing that foundational reading skills are undertaught?

The same universities who claim to be leading research institutions are eerily silent about their failure to apply the research in preparing teaching candidates. Likewise, the K-12 institutions with mission statements citing equity have systematically created a resource gap where those without money to overcome inadequate instruction are consigned to the margins of society while their better-resourced peers seek tutors or more appropriate school placements. Rather than address these issues, we have focused on untangling America’s racial quagmire – as if these things are mutually exclusive. We seem oblivious to the impact race and class have on our tolerance for student failure and our willingness to promote external control narratives that undermine collective teacher efficacy and obfuscate the central issues: we have not provided direct, systematic, explicit instruction to teach reading; neither curricula nor materials have been evidence-based; professional development dollars have not been used well; assessment has been misunderstood and abused; interventions haven’t been timely; and the dearth of humility from leaders and institutions have limited the possibility of effective change management.

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

There’s been a lot of talk recently about the reading crisis in U.S. schools. Careful reporting has pinpointed a common problem: Many newly-trained and veteran teachers are not aware of the latest research on early reading instruction or comprehension. In 2016, NCTQ reviewed the syllabi of 820 teacher preparation programs across the country and found that only 39 percent of programs were teaching the basics of effective reading instruction. Four years later that number of programs has risen to 51 percent. While this signals a positive trend in adopting evidence-informed reading instruction, the fact remains that 49 percent of incoming teachers do not have the tools to effectively teach reading.

After examining our experiences at two well-known teacher training programs in Minnesota and looking at what we were—and were not—taught about the basics of literacy, we have come to the same conclusion: We were not prepared for the responsibility of the job. This failure to prepare teachers, we believe, should be a red flag for the current system in place for how we train and place teachers into classrooms.

NCTQ:

Our nation's schools employ 3 million teachers and rely on 27,000 programs in 2,000 separate institutions for training those teachers. Since 2006, NCTQ has reviewed programs, made recommendations, and highlighted the best we've seen of key elements for undergraduate and graduate programs for elementary, secondary and special education.

Wisconsin DPI’s ongoing efforts to weaken the Foundations of Reading Test for elementary teachers.

This study examines all 50 states’ and the District of Columbia’s requirements regarding the science of reading for elementary and special education teacher candidates.

“Report finds only 11 states have adequate safeguards in place for both elementary and special education teachers.” Make that “10 states”; with Wisconsin PI 34, the loophole (created by a succession of emergency rules) waiving the Foundations of Reading Test is now permanent.

Much more on Tony Evers and Scott Walker, along with Act 10 and the DPI efgort to undermine elementary teacher english content knowledge requirements.

What Should Teachers Know?

Is my experience representative? Are most teachers unaware of the latest findings from basic science—in particular, psychology—about how children think and learn? Research is limited, but a 2006 study by Arthur Levine indicated that teachers were, for the most part, confident about their knowledge: 81 percent said they understood “moderately well” or “very well” how students learn. But just 54 percent of school principals rated the understanding of their teachers that high. And a more recent study of 598 American educators by Kelly Macdonald and colleagues showed that both assessments may be too optimistic. A majority of the respondents held misconceptions about learning—erroneously believing, for example, that children have learning styles dominated by one of the senses, that short bouts of motor-coordination exercises can improve the integration of the brain’s left and right hemispheres, and that children are less attentive after consuming sugary drinks or snacks.

But perhaps when teachers say they “know how children learn,” they are not talking about learning from a scientific perspective but about craft knowledge. They take the question to mean, “Do you know how to ensure that children in your classroom learn?” which is not the same as understanding the theoretical principles of psychology. In fact, in a 2012 study of 500 new teachers by the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), respondents said that their training was too theoretical and didn’t prepare them for teaching “in the real world.” Maybe they have a point. Perhaps teachers don’t need generalized theories and abstractions, but rather ready-to-go strategies—not information about how children learn, but the best way to teach fractions; not how children process negative emotion, but what to say to a 3rd grader who is dejected about his reading.

Related: National Council on Teacher Quality.

More, here.

Robert Vagi Margarita Pivovarova, and Wendy Miedel Barnard:

Recruiting and retaining high-quality teachers has been a long-standing policy issue as states work to alleviate chronic teacher shortages as well as close achievement gaps. Importantly, evidence points to teacher quality as the most important school-based factor that affects student achievement. Unfortunately, it is often difficult for school and district leadership to identify high-quality teachers who will remain in the classroom, especially among those who are just entering the profession and in the first years of employment.

While the vast majority of teachers in the U.S. enter the profession upon receiving roughly four years of traditional university-based training, research that links preservice teacher experiences to their performance and retention once they are in the labor force is lacking. This overlooks the fact that much of our country’s investment in improving teacher quality happens during teachers’ preservice training. Moreover, recent evidence suggests that the context of a student’s preservice teaching is associated with important consequences for their later employment outcomes.

Our recent study adds to a small but growing body of literature that uses data from teachers’ preservice training to better understand how they fare in the classroom after graduation. We were interested in whether a measure of preservice teacher quality could predict entry and retention in the profession. Our data included over 1,100 graduates of a teacher preparation program housed at a large, state university. In addition to having information collected by the university, we were able to track these graduates’ employment using data from the state department of education. Students enrolled in this program complete a year-long student teaching residency that enables them to enter the labor force with the professional experience of a second-year teacher. During the residency, student teachers receive four formal observations by university-trained coaches who assign them evidence-based scores that are later combined into an overall score of effectiveness. This comprehensive score is based on several indicators including student teachers’ instructional and professional practices. Student teachers are expected to respond to their coach’s feedback after each observation and demonstrate improvement over time. We used the score from preservice teachers’ final assessments as an indicator of overall quality and readiness to enter the profession.

Related: NCTQ.

Wisconsin Reading Coalition (PDF), via a kind email:

As we reported recently, districts in Wisconsin, with the cooperation of DPI, have been making extensive use of emergency licenses to hire individuals who are not fully-licensed teachers. Click here to see how many emergency licenses were issued in your district in 2016-17 for elementary teachers, special education teachers, reading teachers, and reading specialists. You may be surprised at how high the numbers are. These are fields where state statute requires the individual to pass the Wisconsin Foundations of Reading Test to obtain a full initial license, and the emergency licenses provide an end-run around that requirement.

These individuals did not need to pass the Wisconsin Foundations of Reading Test, which would be required for full initial licensure *districts include individuals that are listed only once, but worked in multiple locations or positions

Information provided by the Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

New Online Certificate Program

Now there is an even more misguided opportunity for districts to hire unprepared teachers. The budget bill, set for an Assembly vote this Wednesday, followed by a vote in the Senate, requires DPI to issue an initial license to anyone who has completed the American Board online training program. That program, for career switchers with bachelor’s degrees, can be completed in less than one year and includes no student teaching (substitute or para-professional experience is accepted). We have no objection to alternate teacher preparation programs IF they actually prepare individuals to Wisconsin standards. In the area of reading, the way to determine that is for the American Board graduates to take the Wisconsin Foundations of Reading Test (FORT). If they cannot pass, they should not be granted anything more than an emergency license, which is what is available to individuals who complete Wisconsin-based traditional and alternate educator preparation programs but cannot pass the FORT. Wisconsin should not accept American Board’s own internal assessments as evidence that American Board certificate holders are prepared to teach reading to beginning and struggling students.Action Requested

Please contact your legislators and tell them you do not want to weaken Wisconsin’s control over teacher quality by issuing initial licenses to American Board certificate holders who have not, at a minimum, passed the Wisconsin Foundations of Reading Test. Ask them to remove this provision from the budget bill. Find your legislators and contact information here.

How Should Wisconsin Address Its Teacher Shortages?

As pointed out in a recent fact sheet from the National Council on Teacher Quality, teacher shortages are particular to certain fields and geographic areas, and solutions must focus on finding and addressing the reasons for those shortages. This requires gathering and carefully analyzing the relevant data, including the quality of teacher preparation at various institutions, the pay scale in the hiring districts, and the working conditions in the district.

Related: WISCONSIN ELEMENTARY TEACHER CONTENT KNOWLEDGE EXAM RESULTS (FIRST TIME TAKERS).

Am emphasis on adult employment.

“Financially it’s a ticking time bomb, we think,” Ingersoll said. “The main budget item in any school district is teachers’ salaries. This just can’t be sustainable.”

It’s easy to see what Ingersoll means. NCES produces its survey every four years. Almost all public school staffing took a hit during the 2012 survey, as districts laid off thousands during the recession. Hiring was bound to return to normal levels afterwards.

If we go back to 2008 we get a clear picture of the growth of America’s public school workforce. While, student enrollment in 2015-16 was virtually identical to what it was in 2007-08 — almost 49.3 million students — the number of employees in 2016 was substantially higher.The population of teachers grew from 3.4 million to more than 3.8 million — an increase of 12.4 percent.

But teachers comprise only half of the public school labor force. Over the past eight years, the numbers of administrators, bureaucrats, specialists and infrastructure support employees have also ballooned. The ranks of vice principals and assistant principals grew by 8.3 percent. Instructional coordinators and curriculum specialists increased by 10.5 percent, and there was between 5 and 12 percent growth in the number of nurses, psychologists, speech therapists, and special education aides.Again, this larger group of employees is responsible for the same number of students as were enrolled in 2008.

Related: NCTQ “Questions Teacher Shortage Narrative, Release Facts to Set the Record Straight”.

NCTQ (National Council on Teacher Quality):

Our nation has open teaching positions that need to be filled by trained teachers. This is not a new national crisis but rather one America has been living with for years due to our unwillingness to adopt more strategic pay approaches. With rare exceptions, states have also shown no interest in limiting the number of teacher candidates their institutions can accept in some teaching fields to bring down the numbers nor in encouraging candidates to consider other teaching areas in shorter supply.

Teacher shortages are largely a product of local conditions, requiring local solutions. For example, until the state of Oklahoma pays its teachers more, it will struggle to fill positions, but solving its problem does not require us to raise teacher pay everywhere. Detroit suffers because its schools are so challenging. No solution will solve its problem until we address these local environments. The teaching field does not need solutions that set us back, like lowering teacher standards, hiring long-term substitutes and handing out emergency teacher certifications. There has been a mad rush by states to adopt these sorts of solutions. Instead, to fully understand the nature of teacher supply and demand trends, it is incumbent upon the nation, states, and school districts to collect better data and put these data into an historical context. States and districts should be able to identify the number of new teachers trained in each subject, how many graduate and do not end up teaching (because we know that nationwide, 50 percent of candidates do not end up in teaching jobs), where candidates apply for jobs, how many vacancies are open in each subject, and where these vacancies are located. In the absence of strong data systems that can pinpoint the broken points along the teacher pipeline, states and districts will continue to look for band-aids without resolving the underlying problems and the very real shortages which are not new but have gone on now for decades.

NCTQ Questions Teacher Shortage Narrative, Release Facts to Set the Record Straight.

A group of school officials, including state Superintendent Tony Evers, is asking lawmakers to address potential staffing shortages in Wisconsin schools by making the way teachers get licensed less complicated.

The Leadership Group on School Staffing Challenges, created by Evers and Wisconsin Association of School District Administrators executive director Jon Bales, released last week a number of proposals to address shortages, including reducing the number of licenses teachers must obtain to be in a classroom.

Under the group’s proposal, teachers would seek one license to teach prekindergarten through ninth grade and a second license to teach all grades, subjects and special education.

The group also proposes to consolidate related subject area licenses into single subject licenses. For example, teachers would be licensed in broad areas like science, social studies, music and English Language Arts instead of more specific areas of those subjects.

Wisconsin adopted Massachusett’s (MTEL) elementary reading content knowledge requirements (just one, not the others).

Much more on Wisconsin and MTEL, here.

National Council on Teacher Quality ranks preparation programs…. In 2014, no Wisconsin programs ranked in the top group.

Foundations of Reading Results (Wisconsin’s MTEL):

Wisconsin’s DPI provided the results to-date of the Wisconsin Foundations of Reading exam to School Information System, which posted an analysis. Be aware that the passing score from January, 2014 through August, 2014, was lower than the passing score in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Since September of 2014, the Wisconsin passing score has been the same as those states. SIS reports that the overall Wisconsin pass rate under the lower passing score was 92%, while the pass rate since August of 2014 has been 78%. This ranges from around 55% at one campus to 93% at another. The pass rate of 85% that SIS lists in its main document appears to include all the candidates who passed under the lower cut score.

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction’s proposed changes: Clearinghouse Rule 16 PROPOSED ORDER OF THE STATE SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION REVISING PERMANENT RULES

A kind reader’s comments:

to wit “Of particular concern is the provision of the new rule that would allow teachers who have not otherwise met their licensure requirements to teach under emergency licenses while “attempting to complete” the required licensure tests. For teachers who should have appropriate skills to teach reading, this undercuts the one significant achievement of the Read to Lead workgroup (thanks to Mark Seidenberg)—that is, requiring Wisconsin’s elementary school and all special education teachers to pass the Foundations of Reading test at the MTEL passing cut score level. The proposed DPI rule also appears to conflict with ESSA, which eliminated HQT in general, but updated IDEA to incorporate HQT provisions for special education teachers and does not permit emergency licensure. With reading achievement levels in Wisconsin at some of the lowest levels in the nation for the student subgroups that are most in need of qualified instruction, the dangers to students are self-evident”.

Related, from the Wisconsin Reading Coalition [PDF]:

Wisconsin 4th Grade Reading Results on the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP)

Main takeaways from the 2015 NAEP 4th grade reading exam:

Statements by our Department of Public Instruction that there was a “positive upward movement” in reading (10/28/15 News Release) and especially that our 4th graders “might be viewed” as ranking 13th in 4th grade reading (11/5/15 DPI-ConnectEd) are inaccurate and misleading.

Proficiency Rates and Performance Gaps

Overall, 8% of Wisconsin 4th graders are advanced, 29% are proficient, 34% are basic, and 29% are below basic. Nationally, 9% of students are advanced, 27% are proficient, 33% are basic, and 31% are below basic.

As is the case around the country, some student groups in Wisconsin perform better than others, though only English Language Learners outperform their national peer group. Several groups are contrasted below.

Subgroups can be broken down by race, gender, economic status, and disability status. 44% of white students are proficient or advanced, versus 35% of Asian students, 23% of American Indian students, 19% of Hispanic students and 11% of African-American students. 40% of girls are proficient or advanced, compared to 34% of boys. Among students who do not qualify for a free or reduced lunch, 50% are proficient or advanced, while the rate is only 19% for those who qualify. Students with disabilities continue to have the worst scores in Wisconsin. Only 13% of them are proficient or advanced, and a full 68% are below basic, indicating that they do not have the skills necessary to navigate print in school or daily life. It is important to remember that this group does not include students with severe cognitive disabilities.

When looking at gaps between sub-groups, keep in mind that a difference of 10 points on The NAEP equals approximately one grade level in performance. Average scores for Wisconsin sub-groups range from 236 (not eligible for free/reduced lunch) to 231 (white), 228 (students without disabilities), 226 (females), 225 (non-English Language Learners), 222 (Asian), 220 (males), 209 (Hispanic), 207 (American Indian or eligible for free/reduced lunch), 198 (English Language Learners), 193 (African-American), and 188 (students with disabilities). There is a gap of almost three grade levels between white and black 4th graders, and four grade levels between 4th graders with and without disabilities.

Scores Viewed Over Time

The graph below shows NAEP raw scores over time. Wisconsin’s 4th grade average score in 2015 is 223, which is statistically unchanged from 2013 and 1992, and is statistically the same as the current national score (221). The national score, as well as scores in Massachusetts, Florida, Washington, D.C., and other jurisdictions, have seen statistically significant increases since 1992.

Robust clinical and brain research in reading has provided a roadmap to more effective teacher preparation and student instruction, but Wisconsin has not embraced this pathway with the same conviction and consistency as many other states. Where change has been most completely implemented, such as Massachusetts and Florida, the lowest students benefitted the most, but the higher students also made substantial gains. It is important that we come to grips with the fact that whatever is holding back reading achievement in Wisconsin is holding it back for everyone, not just poor or minority students. Disadvantaged students suffer more, but everyone is suffering, and the more carefully we look at the data, the more obvious that becomes.

Performance of Wisconsin Sub-Groups Compared to their Peers in Other Jurisdictions

10 points difference on a NAEP score equals approximately one grade level. Comparing Wisconsin sub-groups to their highest performing peers around the country gives us an indication of the potential for better outcomes. White students in Wisconsin (score 231) are approximately three years behind white students in Washington D.C. (score 260), and a year behind white students in Massachusetts (score 242). African-American students in Wisconsin (193) are more than three years behind African-American students in Department of Defense schools (228), and two years behind their peers in Arizona and Massachusetts (217). They are approximately one year behind their peers in Louisiana (204) and Mississippi (202). Hispanic students in Wisconsin (209) are approximately two years behind their peers in Department of Defense schools (228) and 1-1/2 years behind their peers in Florida (224). Wisconsin students who qualify for free or reduced lunch (207) score approximately 1-1/2 years behind similar students in Florida and Massachusetts (220). Wisconsin students who do not qualify for free and reduced lunch (236) are the highest ranking group in our state, but their peers in Washington D.C. (248) and Massachusetts (247) score approximately a grade level higher.

State Ranking Over Time

Wisconsin 4th graders rank 25th out of 52 jurisdictions that took the 2015 NAEP exam. In the past decade, our national ranking has seen some bumps up or down (we were 31st in 2013), but the overall trend since 1998 is a decline in Wisconsin’s national ranking (we were 3rd in 1994). Our change in national ranking is entirely due to statistically significant changes in scores in other jurisdictions. As noted above, Wisconsin’s scores have been flat since 1992.

The Positive Effect of Demographics

Compared to many other jurisdictions, Wisconsin has proportionately fewer students in the lower performing sub-groups (students of color, low-income students, etc.). This demographic reality allows our state to have a higher average score than another state with a greater proportion of students in the lower performing sub-groups, even if all or most of that state’s subgroups outperform their sub-group peers in Wisconsin. If we readjusted the NAEP scores to balance demographics between jurisdictions, Wisconsin would rank lower than 25th in the nation. When we did this demographic equalization analysis in 2009, Wisconsin dropped from 30th place to 43rd place nationally.

Applying Standard Statistical Analysis to DPI’s Claims

In its official news release on the NAEP scores on October 28, 2015, DPI accurately stated that Wisconsin results were “steady.” After more than a decade of “steady” scores, one could argue that “flat” or “stagnant” would be more descriptive terms. However, we cannot quibble with “steady.” We do take issue with the subtitle “Positive movement in reading,” and the statement that “There was a positive upward movement at both grade levels in reading.” In fact, the DPI release acknowledges in the very next sentence, “Grade level scores for state students in both mathematics and reading were considered statistically the same as state scores on the 2013 NAEP.” The NAEP website points out that Wisconsin’s 4th grade reading score was also statistically the same as the state score on the 2003 NAEP, and this year’s actual score is lower than in 1992. It is misleading to say that there has been positive upward movement in 4th grade reading. (emphasis added).

Regarding our 4th grade ranking of 25th in the nation, DPI’s ConnectEd newsletter makes the optimistic, but unsupportable, claim that “When analyzed for statistical significance, the state’s ranking might be viewed as even higher: “tied” for . . . 13th in fourth grade reading.”

Wisconsin is in a group of 16 jurisdictions whose scores (218-224) are statistically the same as the national average (221). 22 jurisdictions have scores (224-235) statistically above the national average, and 14 have scores (207-218) statistically below the national average. Scoring third place in that middle group of states is how NAEP assigned Wisconsin a 25th ranking.

When we use Wisconsin as the focal jurisdiction, 12 jurisdictions have scores (227-235) statistically higher than ours (223), 23 jurisdictions have scores (220-227) that are statistically the same, and 16 have scores (207-219) that are statistically lower. This is NOT the same as saying we rank 13th.

To assume we are doing as well as the state in 13th place is a combination of the probability that we are better than our score, and they are worse than theirs: that we had very bad luck on the NAEP administration, and that other state had very good luck. If we took the test again, there is a small probability, less than 3%, that our score would rise and theirs would fall, and we would meet in the middle, tied for 19th, not 13th, place. The probability that the other state would continue to perform just as well and we would score enough better to move up into a tie for 13th place is infinitesimal: a tiny fraction of a percentage. Not only is that highly unlikely, it is no more true than saying we could be viewed as tied with the jurisdiction at the bottom of our group, ranking 36th.

Furthermore, this assertion requires us to misuse not only this year’s data, but the data from past years which showed us at more or less the same place in the rankings. When you look at all the NAEP data across time and see how consistent the results are, the likelihood we are actually much better than our current rank shrinks to nearly nothing. It would require that not only were we incredibly unlucky in the 2015 administration, but we have been incredibly unlucky in every administration for the past decade. The likelihood of such an occurrence would be in the neighborhood of one in a billion billion.

Until now, DPI has never stated a reason for our mediocre NAEP performance. They have always declined to speculate. And now, of all the reasons they might consider to explain why our young children read so poorly and are falling further behind students in other states, they suggest it may just be bad luck. Whether they really believe that, or are tossing it out as a distraction from the actual facts is not entirely clear. Either way, it is a disappointing reaction from the agency that jealously guards its authority to guide education in Wisconsin.

Wisconsin Reading Coalition PDF summary.

National Council on Teacher Quality:

No parent wants his or her child to be taught by an ineffective teacher. As the school year begins each September, parents sometimes worry that their child’s teacher may not be able to manage the classroom, may not be able to inspire students to reach higher levels of learning, or simply may not be up to the job. These worries grow when a teacher is new to the classroom, teaching without the bene t of a few years of experience. The responsibility for these worries often falls on a state’s teacher preparation programs, so it is crucial that the programs set high standards to admit only the best candidates.

A strong body of research supports a relationship between student performance and the selectivity of admissions into teacher preparation. Nations, such as Finland, whose students outperform ours on national tests recruit teacher candidates from the top 10 percent of their college graduates. High admissions standards are especially important because after a candidate is admitted to a preparation program, he or she will probably face few hurdles for entry into the profession.

State admissions standards rose between 2011 and 2015 and fell in 2016

Raising the bar for entry into preparation programs resonates with states and school districts, which certainly recognize the importance of attracting talented college students into the teaching profession. As a result, 25 states strengthened admissions standards between 2011 and 2015, with 11 states establishing higher admissions standards through state law and 14 states doing so through national accreditation. The number of states establishing a minimum 3.0 GPA requirement went from seven in 2013 to 25 in 2015, and the number requiring that teacher candidates take tests designed for all college students (such as the ACT or SAT) went from three to 19 during that same time. While both approaches have advantages and limitations, some states have put forward admissions policies that employ multiple measures and exibility.

Why teacher prep programs should have strong preparation in elementary mathematics

Teaching elementary children the fundamentals of arithmetic—dividing fractions, operations with signed numbers, or basic probability—requires a deep understanding of the underlying mathematics. For elementary teachers, it’s simply not suf cient just to know “invert and multiply.” One must know and be able to explain why that works, building upon the more fundamental whole number operations. This requires specialized mathematics coursework speci cally for prospective elementary teachers. Typical college-level coursework (such as calculus) does not address these topics.

To earn an A in elementary mathematics, a program must dedicate suf cient time for at least 75 percent of topics identi ed by mathematicians as being critical for elementary teachers, and require at least one course in the methods of teaching mathematics to elementary-aged children.For more information about analysis and program grades, see the Methodology in brief and Understanding program grades sections below.

Much more on nctq.

Yet my children’s experience of school in America is in some ways as indifferent as their swimming classes are good, for the country’s elementary schools seem strangely averse to teaching children much stuff. According to the OECD’s latest international education rankings, American children are rated average at reading, below average at science, and poor at maths, at which they rank 27th out of 34 developed countries. At 15, children in Massachusetts, where education standards are higher than in most states, are so far behind their counterparts in Shanghai at maths that it would take them more than two years of regular education to catch up.

This is not for lack of investment. America spends more on educating its children than all but a handful of rich countries. Nor is it due to high levels of inequality: the proportion of American children coming from under-privileged backgrounds is about par for the OECD. A better reason, in my snapshot experience of American schooling, is a frustrating lack of intellectual ambition for children to match the sporting ambition that is so excellently drummed into them in our local swimming pool and elsewhere.

My children’s elementary school, I should say, is one of America’s better ones, and in many ways terrific. It is orderly, friendly, well-provisioned and packed with the sparky offspring of high-achieving Washington, DC, commuters. Its teachers are diligent, approachable and exude the same relentless positivity as the swimming instructors. We feel fortunate to have them. Yet the contrast with the decent London state school from which we moved our eldest children is, in some ways, dispiriting.

After two years of school in England, our six-year-old was so far ahead of his American peers that he had to be bumped up a year, where he was also ahead. This was partly because American children start regular school at five, a year later than most British children; but it was also for more substantive reasons.

Related: Connected Math, Discovery Math and the Math Forum (audio and video).

Reading requires attention as well. (MTEL)

Locally, Madison has long tolerated disastrous reading results despite spending more than most, now around $18k per student.

And, National Council on teacher quality links are worth a look.

the nation’s schoolteachers get a lot more time for planning lessons than others. A new analysis found that elementary school teachers in Montgomery County, Md., top the list, getting more planning time than their counterparts in 147 large U.S. school districts.