Two Madison School Board seats will be decided by voters on April 7, and the Cap Times will bring together the candidates for each seat in a public forum on Wednesday, March 11, at La Follette High School.

The moderators will be Cap Times education reporter Erin Gretzinger and Taylor Kilgore of the Simpson Street Free Press, which provides journalism and writing training for Dane County students in grades 3 through 12.

The candidates for the two seats are:

Seat 6: Blair Mosner Feltham and Daniella Molle

Seat 7: Dana Colussi-Lynde and Nicki Vander Meulen

The forum is free and will run 7-8 p.m. in Room 1353 at La Follette High, 702 Pflaum Road. To get to Room 1353, enter the high school through its Arts Entrance from the main parking lot, and look for signs and greeters to guide you to the room.

——-

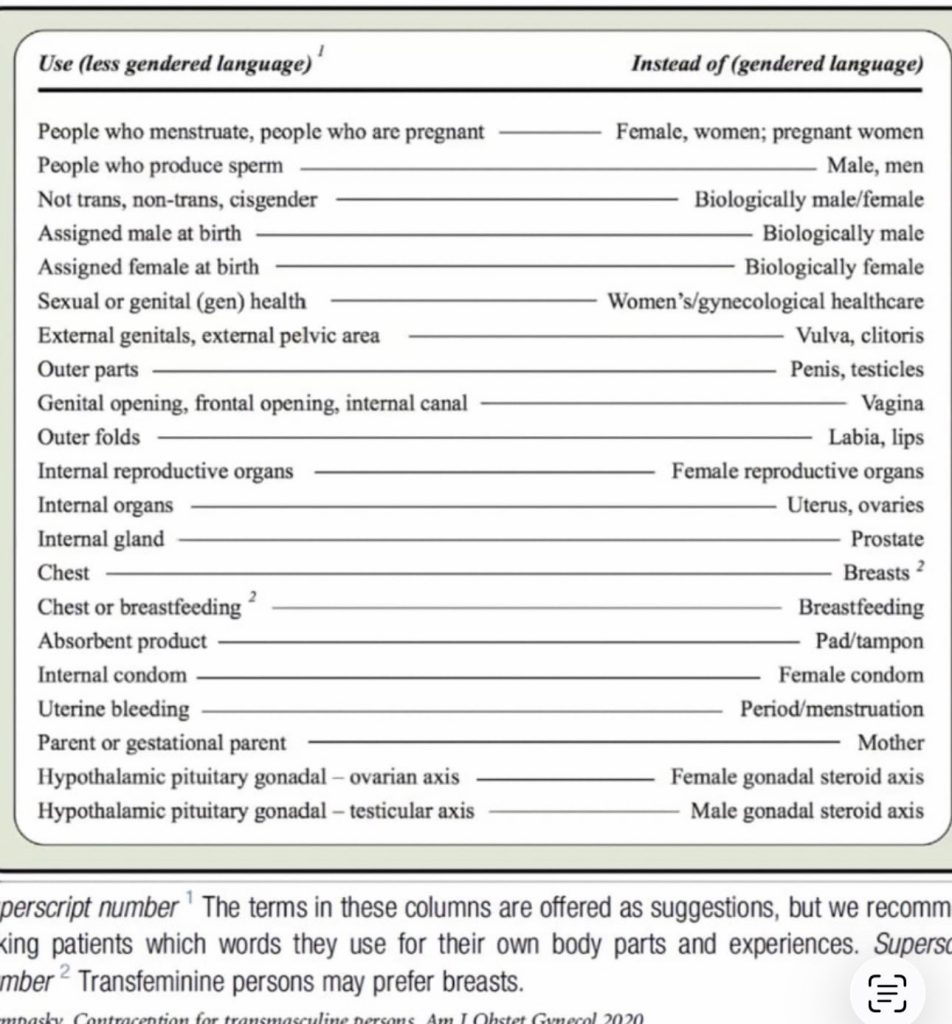

1998! Money and school performance.

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

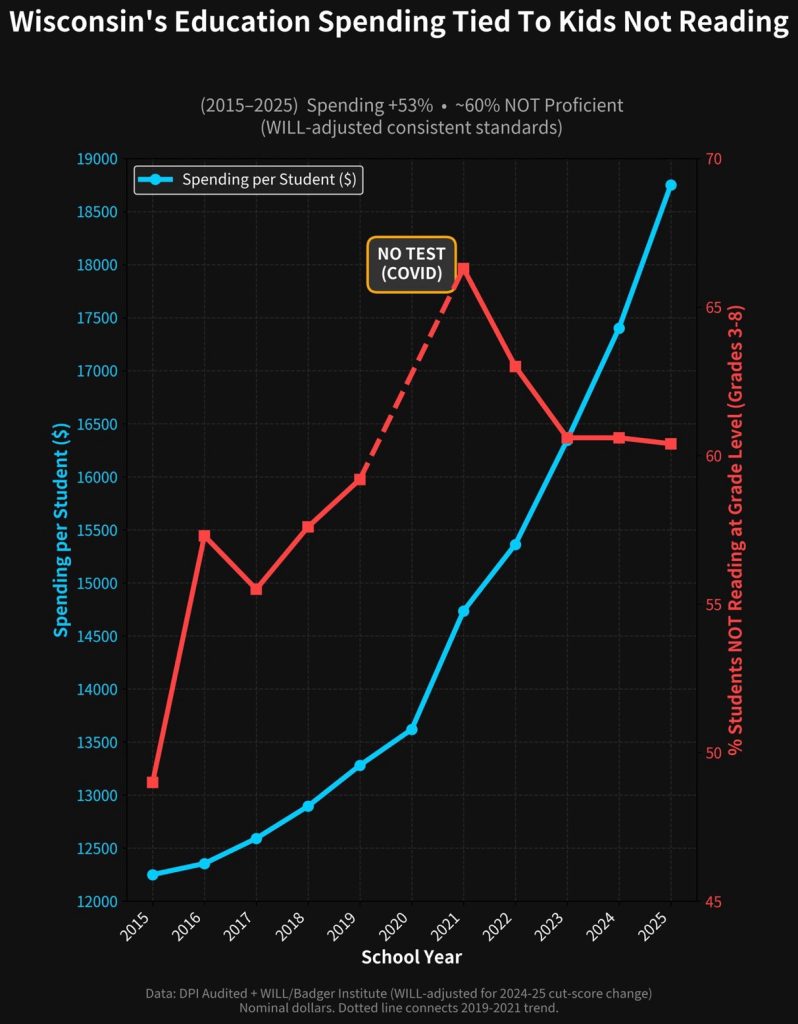

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

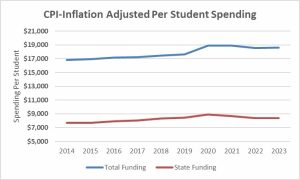

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy