Jason Riley:

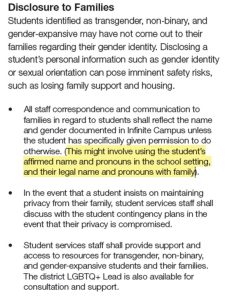

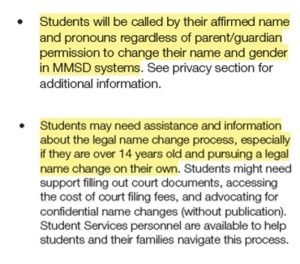

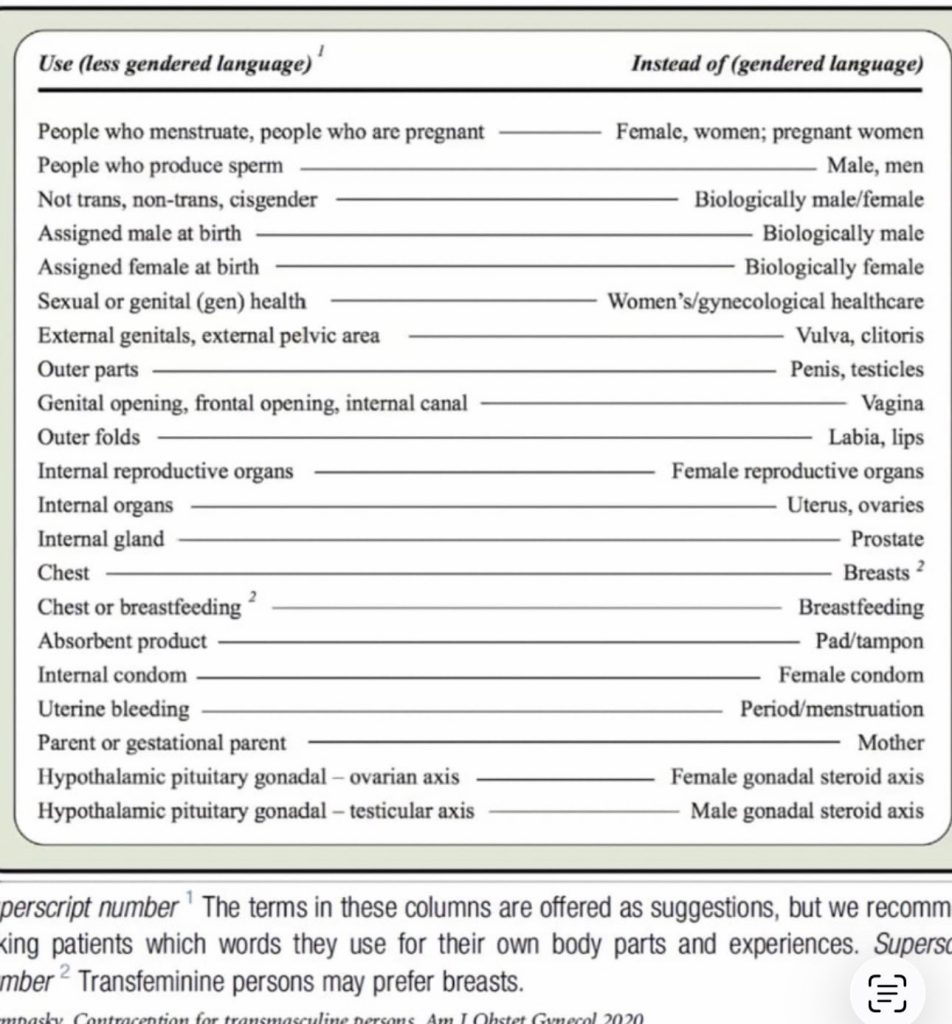

Far too many children are still assigned to substandard schools, and too many remain unable to read or do math at grade level. Meanwhile, educators and policymakers seem preoccupied with nonsense like helping students “transition” behind their parents’ backs or indoctrinating impressionable youngsters with social-justice poppycock to promote trendy political causes. American kids are outperformed by their foreign peers on international exams while we have to concern ourselves with whether school libraries make sexually explicit texts available to third-graders.

For a growing number of people in charge of the public education establishment, making sure that boys can play on girls’ sports teams has become more important than making sure students are acquiring basic academic skills that will enable them to learn a trade, complete college, become productive adults.

One of the few bright spots in our education system has been selective-enrollment public high schools, which use standardized tests and other objective measures to determine admissions. Examples include Boston Latin School in Massachusetts, Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan and Thomas Jefferson High School in Alexandria, Va., all of which boast long and proven records of providing a rigorous education for students from all backgrounds. Yet even this successful model is increasingly under attack, and its future is uncertain.

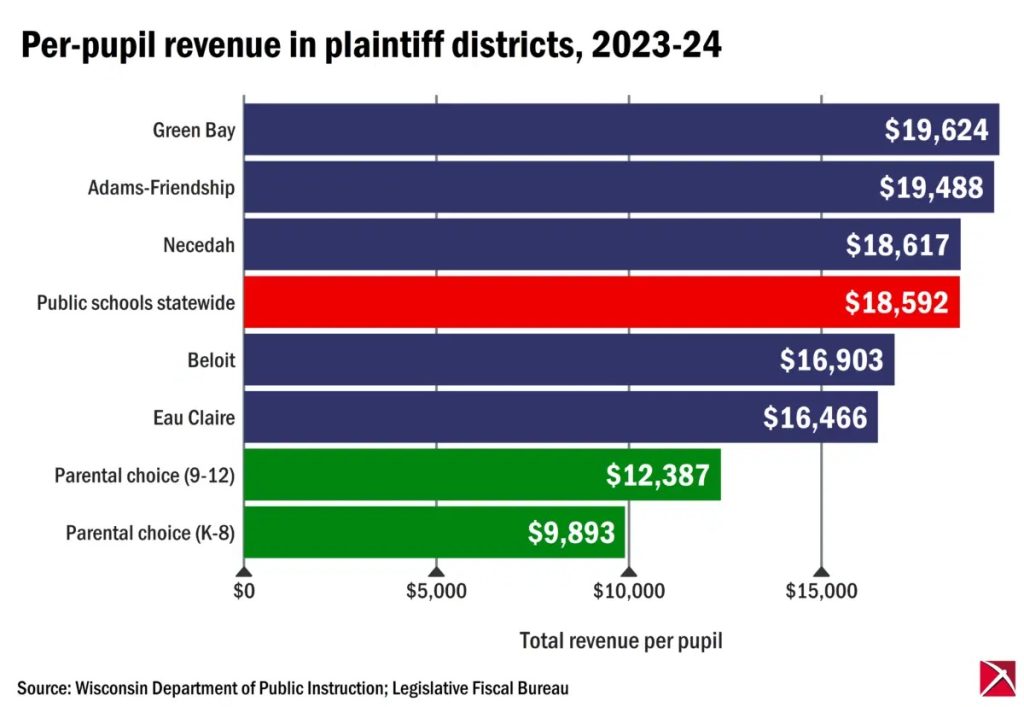

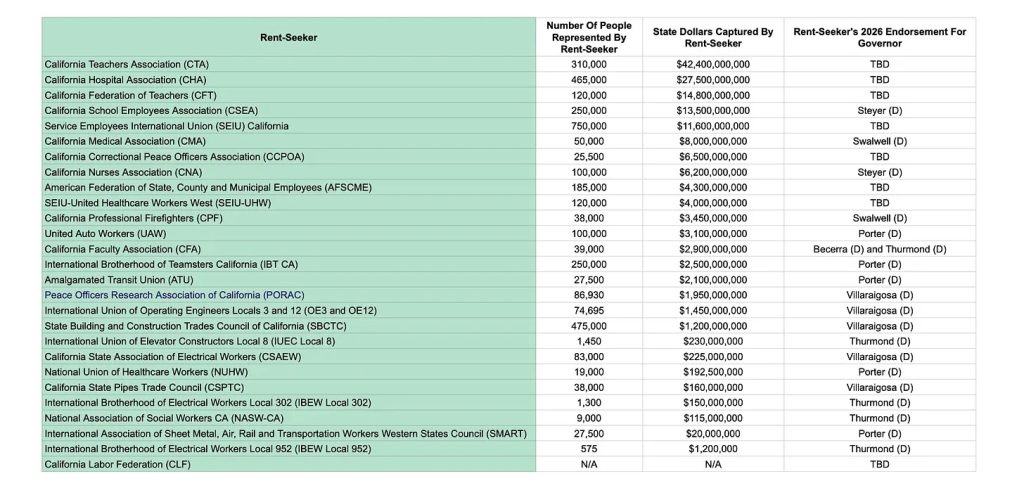

A new study from the Manhattan Institute details efforts in Chicago to eliminate selective public high schools. Much of the Chicago public school system is in shambles. Wirepoints, a government watchdog group, reported last year that the Chicago Public School system operated 53 schools in 2024 where not a single student tested proficient in math, and 17 schools in which no student tested proficient in reading. Mayor Brandon Johnson and other Democrats blame these outcomes on a lack of resources, but spending per pupil has almost doubled since 2017, and teacher pay in the Windy City is among the highest in the nation for large school districts after adjusting for cost of living.

——-

Daniel Friedman:

I believe the reason black and Latino kids do so much worse than white and Asian kids is that large urban public school districts that educate most of these students are incredibly wasteful with resources and adhere to politically progressive methods of teaching that stifle talented students and don’t help low performers. But it’s not a high bar to be better than schools in Central America or Africa.

———

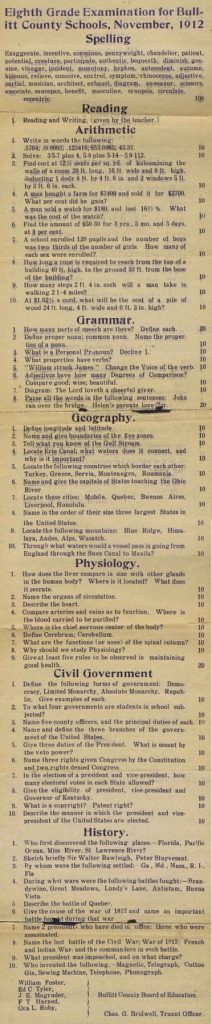

1998! Money and school performance.

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

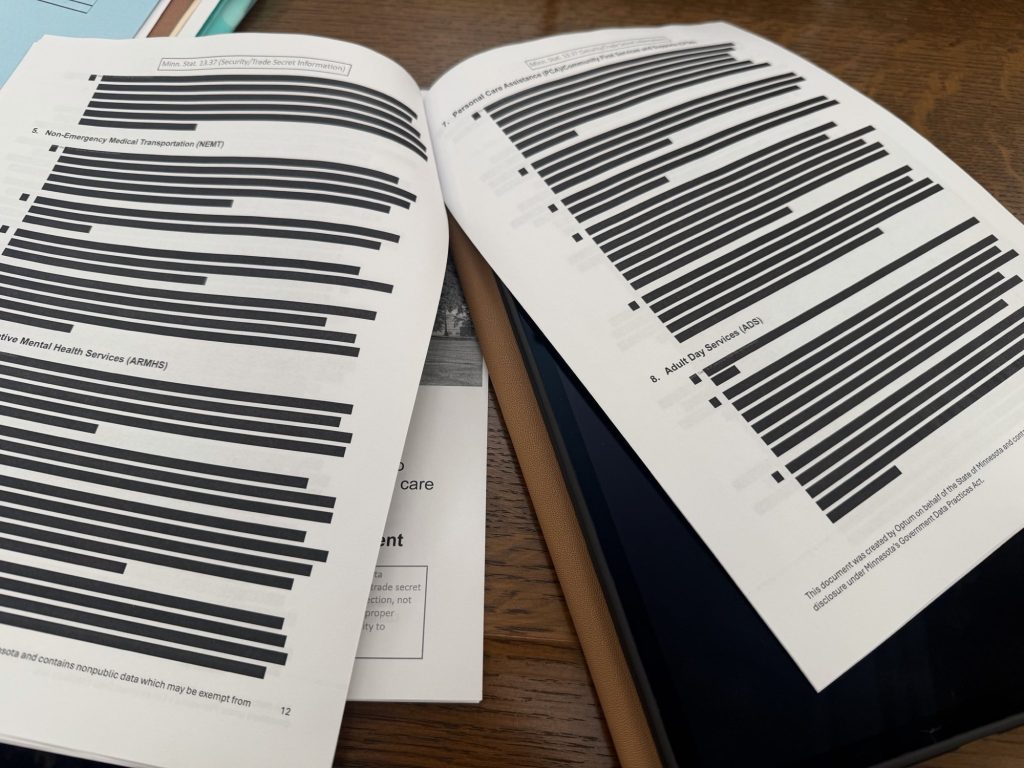

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy