Deborah Fallows:

It’s more than just talk. Many of the older students told us about the college level courses they had taken at WCPA as part of the school’s Pathways program, and how they appreciated the different style of teaching and demands of coursework. Professors from nearby Bakersfield College teach Pathway classes at WCPA; 100% of students take some of their courses, and 50% earn enough credits for an Associates degree by the time they graduate. This is a huge jumpstart in time and money toward a BA, which means a lot to large numbers of students and their families.

One by one, the older students walked-and-talked with us as we toured the campus. Here are some of the highlights we saw and heard about:

Soldiers of Change: The school sponsors a shark-tank like program for projects addressing social change. The students organize themselves into small groups, survey the other students for ideas, collect topics, and make their pitches. Judges listen, award winners, and approve budgets. A recent winner used food (always a hit). Their project was to present new cuisines as intros to new cultures, in the school cafeteria. One boy raved about Indian food, and his first-ever bites.

It’s more than just talk. Many of the older students told us about the college level courses they had taken at WCPA as part of the school’s Pathways program, and how they appreciated the different style of teaching and demands of coursework. Professors from nearby Bakersfield College teach Pathway classes at WCPA; 100% of students take some of their courses, and 50% earn enough credits for an Associates degree by the time they graduate. This is a huge jumpstart in time and money toward a BA, which means a lot to large numbers of students and their families.

One by one, the older students walked-and-talked with us as we toured the campus. Here are some of the highlights we saw and heard about:

Soldiers of Change: The school sponsors a shark-tank like program for projects addressing social change. The students organize themselves into small groups, survey the other students for ideas, collect topics, and make their pitches. Judges listen, award winners, and approve budgets. A recent winner used food (always a hit). Their project was to present new cuisines as intros to new cultures, in the school cafeteria. One boy raved about Indian food, and his first-ever bites.

…….

Learning Farm and Harvest Hall: At the school’s on-site garden, called the Learning Farm, students learn to grow and harvest crops. The results show up frequently in the school cafeteria, to the delight of the young farmers. One of our guides reported an overheard conversation, “Hey, those are my tomatoes you’re eating. I’ve been growing those and now they’re on your flatbread! Check out my tomatoes!”

Beginning in 7th grade, in the classrooms and kitchen, students learn how to build and cook meals, and even take home ideas to their families. On any given day, high schoolers may be prepping the food, serving the meals, doing the checkout. Besides imparting these practical, lifelong skills, there is a higher purpose for the emphasis on nutritious food. Here in the Central Valley, which provides about 25 % of America’s food supply, WCPA is developing and nurturing a sophisticated sense of the ecosystem of agriculture, nutrition, and business. But also, here in Kern County, home to both Lost Hills and Delano, the rate of obesity is 49% and of diabetes, nearly 9%. So, WCPAs are starting early to build good foundations and break bad cycles. The adults emphasized to us that they’re “stamping” the kids with an understanding and experience in managing every aspect of this place-based asset of the food culture that surrounds them. “That’s a piece that we see as vital.”

———

more.

———

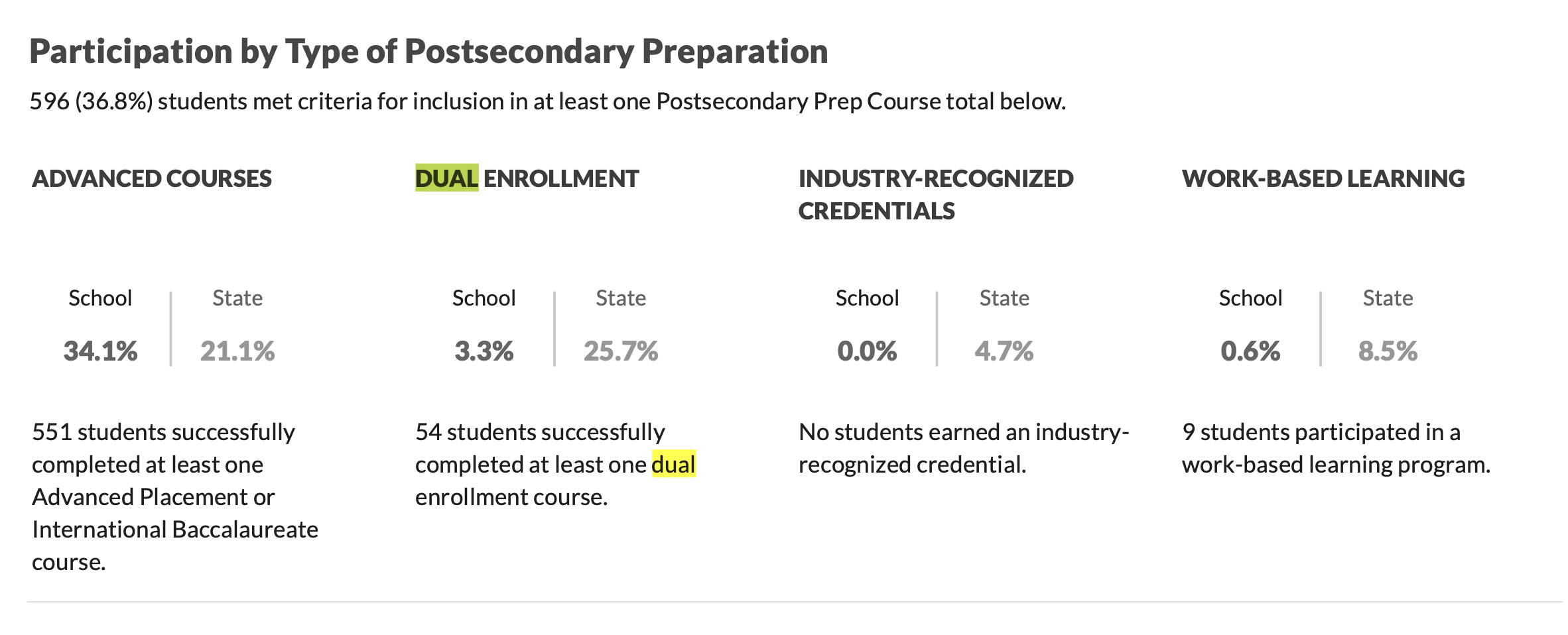

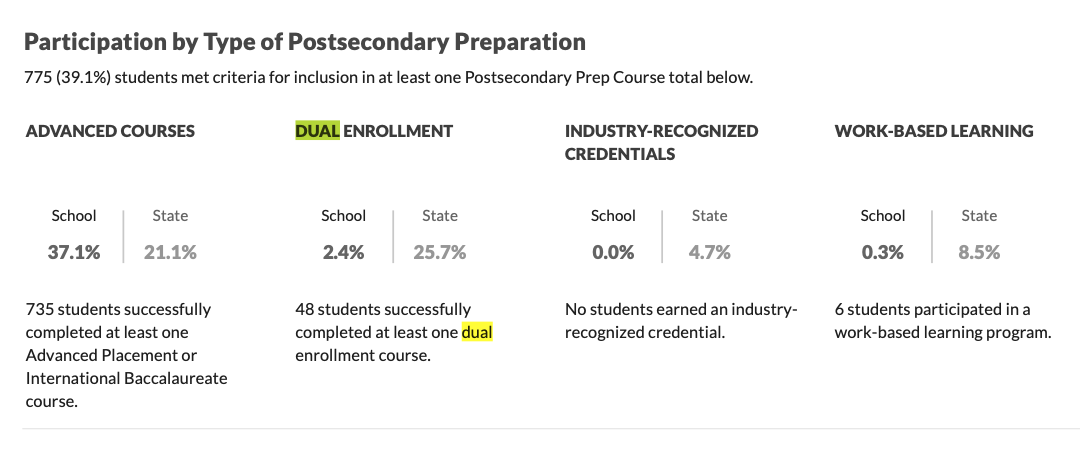

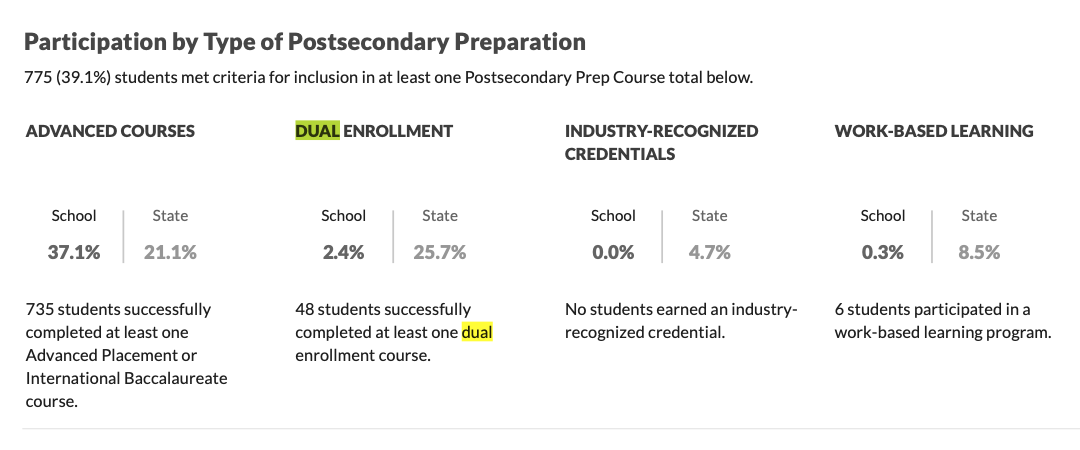

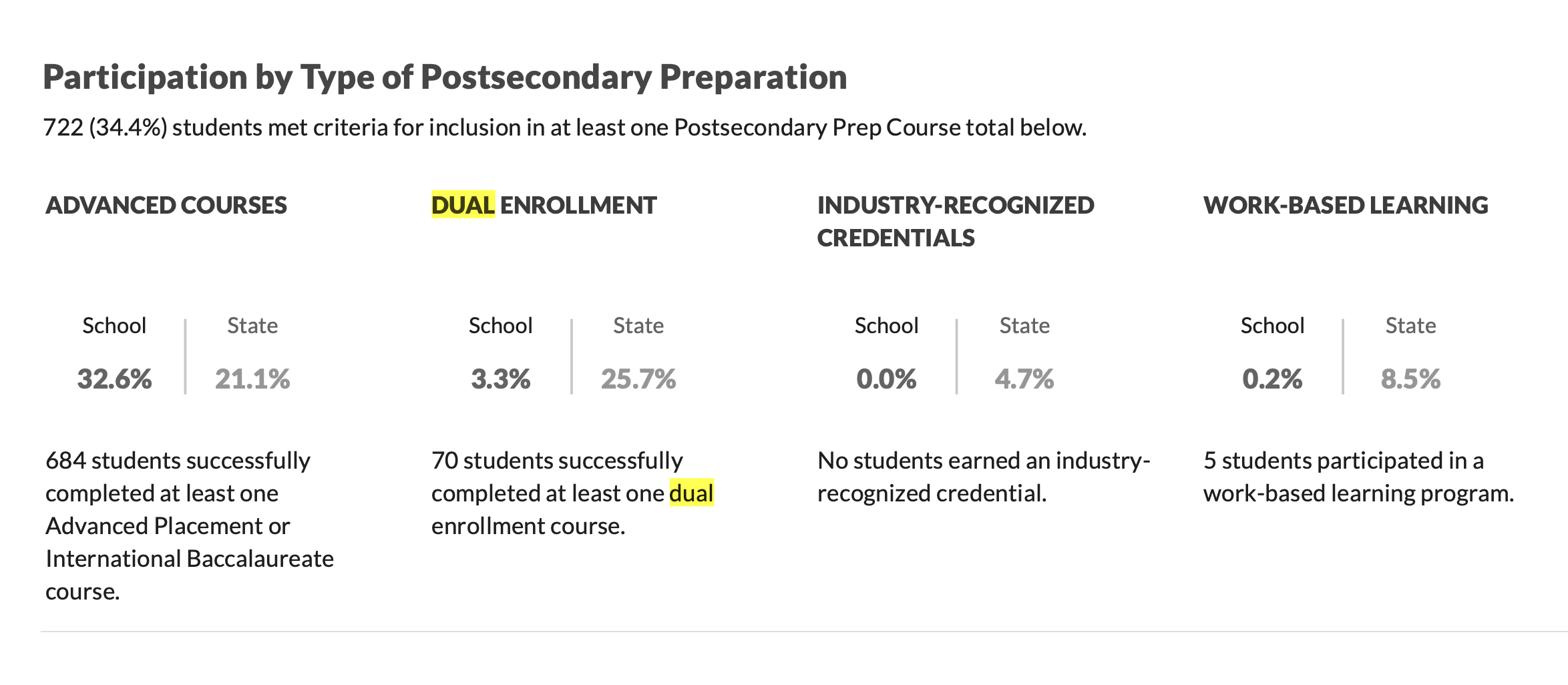

Notes and links on dual enrollment.

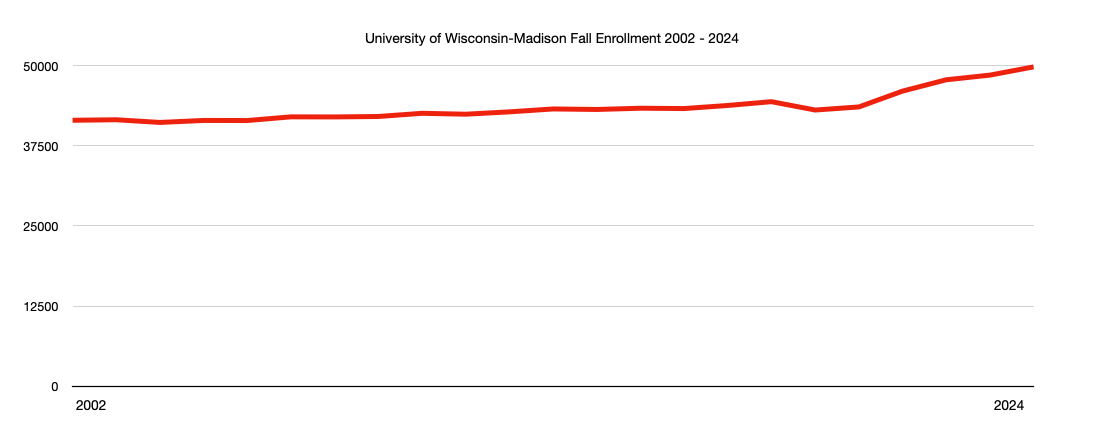

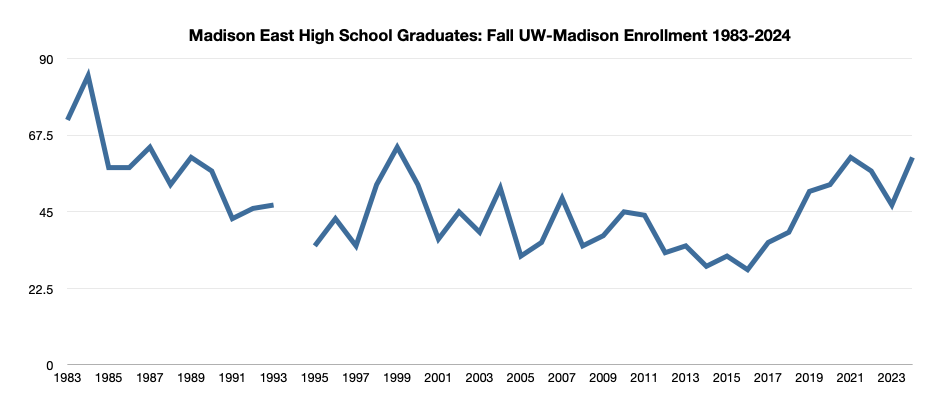

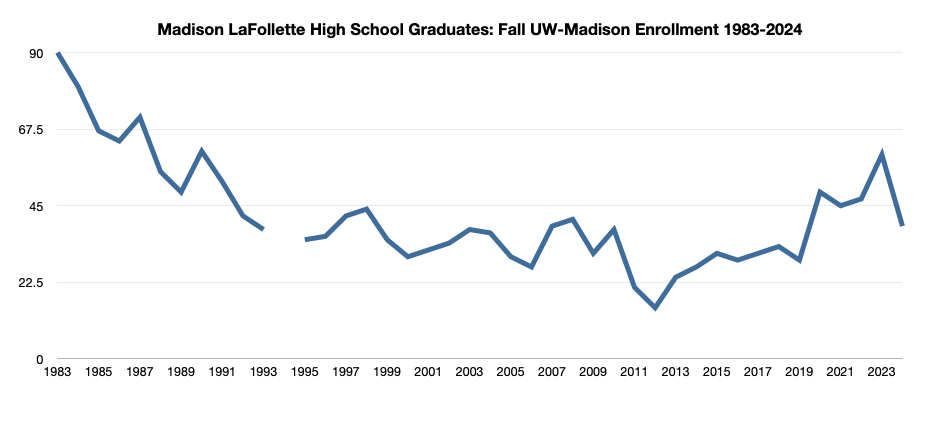

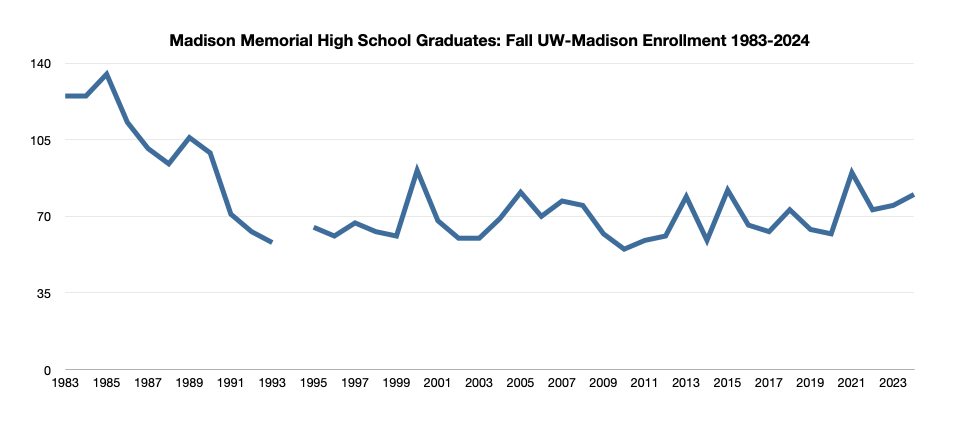

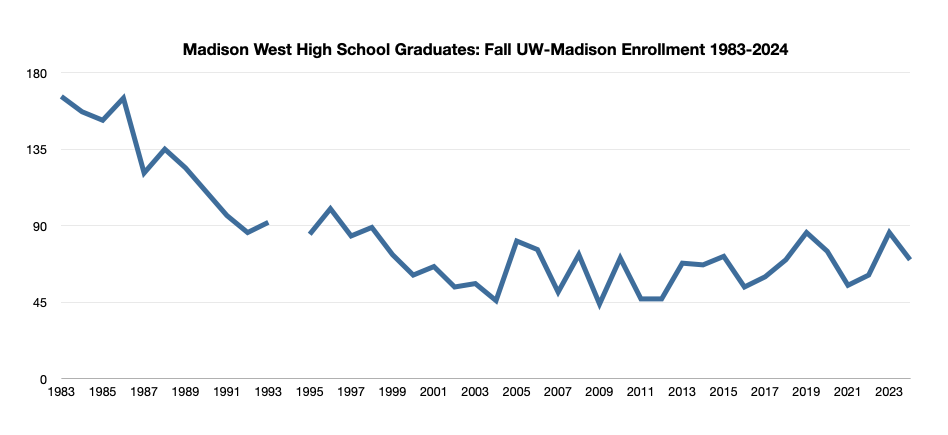

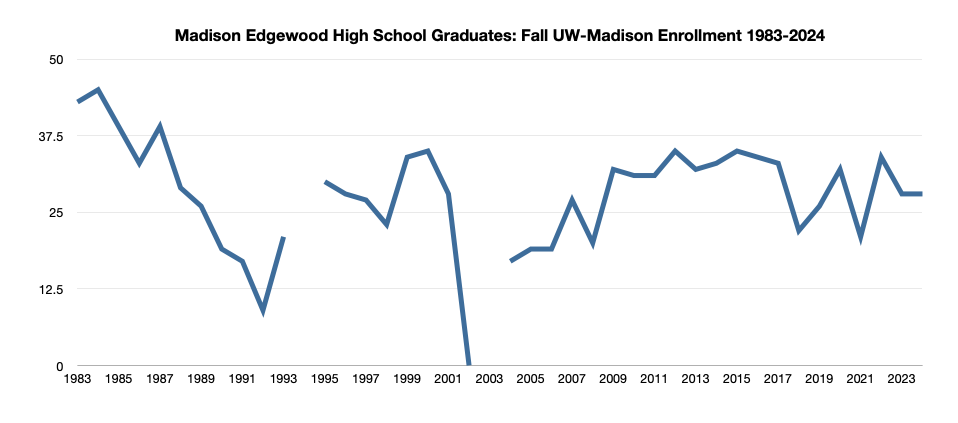

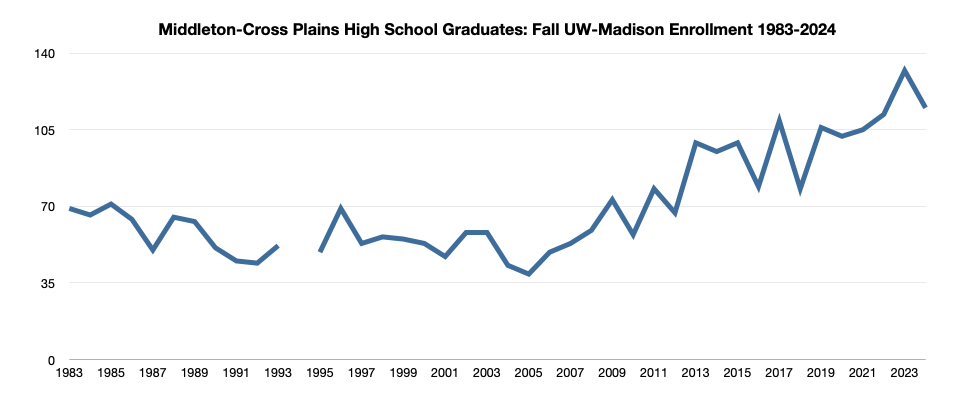

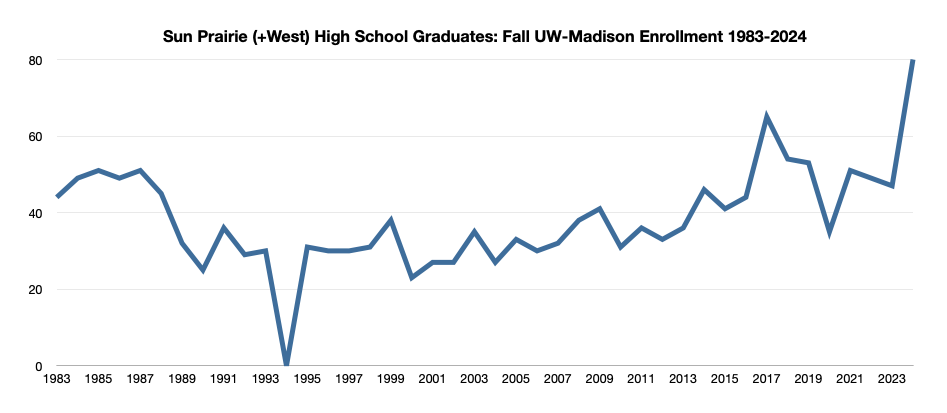

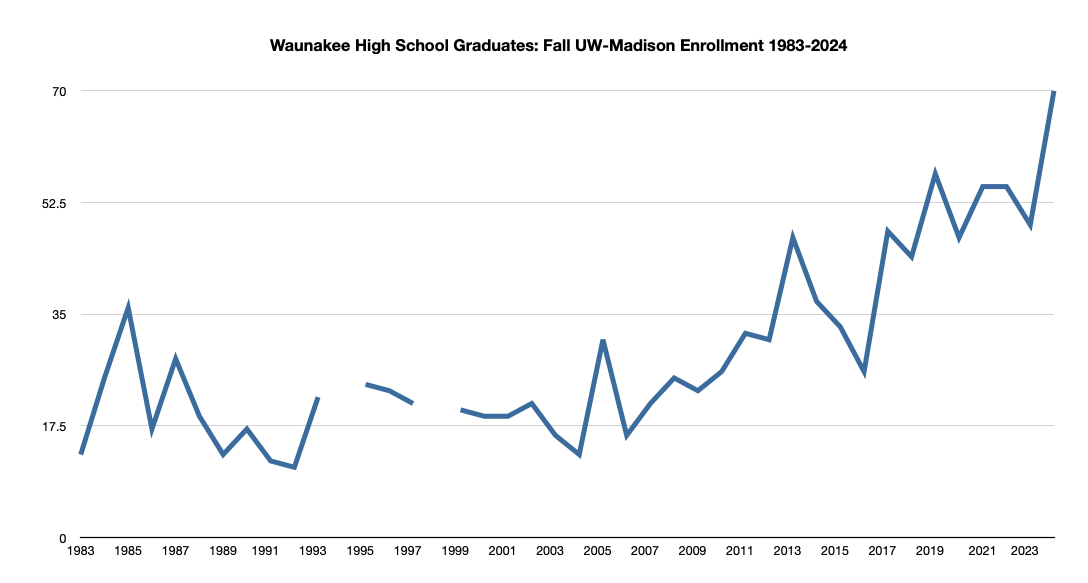

Madison High Schools & University of Wisconsin-Madison Enrollment: A Recent History