Search Results for: seidenberg

Mark Seidenberg Talk on the Science of Reading

Video Audio and transcript as well. Notes and links on Mark Seidenberg.

Wisconsin Education Committee Hearing March 2, 2023: Mark Seidenberg’s Talk, and Q&A

Video mp3 Audio Transcript Additional testimony: Kymyona Burk Instructional Coach Kyle Thayse DPI 3 Minute Summary by Senator Duey Stroebel 2021’s AB446 was mentioned. The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic” My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans […]

“Too often, according to Mark Seidenberg’s important, alarming new book, “Language at the Speed of Sight,” Johnny can’t read because schools of education didn’t give Johnny’s teachers the proper tools to show him how”

Wisconsin Reading Coalition: UW-Madison’s Mark Seidenberg, Vilas Research Professor and Donald O. Hebb Professor of Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience, has a long-standing commitment to using the science of reading to improve educational outcomes. Examples of insightful publications from Seidenberg and his colleagues in recent years include: Language Variation and Literacy Learning: The Case of African […]

Mark Seidenberg on the Reading First controversy

Via a reader email; Language Log: Last Friday, the New York Times ran a story about how school administrators in Madison, Wisconsin, turned down $2M in federal Reading First funds rather than change their approach to the teaching of reading (Diana Jean Schemo, “In War Over Teaching Reading, a U.S.-Local Clash”). Considering the importance of […]

Seidenberg’s Recent “Informal Talk on Reading Education”

University of Wisconsin Psychology Professor [Language and Cognitive Neuroscience Lab] Mark Seidenberg recently gave a lecture on reading education at the University Club: Whole Language was a massive, uncontrolled experiment, with millions of children as unwitting subjects. How it’s done: Someone gets an idea Often a Guru. Many Gurus in reading instruction. Guru has brilliant […]

The Calkins Legacy

Maryellen MacDonald & Mark Seidenberg Calkins became a lightning rod because she represented the sheer intransigence of educators in the face of evidence that their methods for teaching reading were ineffective and ill-conceived. Calkins has now conceded that problems with her approach discussed in Emily Hanford’s Sold a Story were real. The problems were not small ones. Calkins […]

Notes on UW-Madison School of Education Literacy skills

Quinton Klabon: Dean Haddix will oversee science of reading rollout at UW-Madison. Her literacy research focused elsewhere, but the group of which she was president wrote a nuanced defense of balanced literacy and called out UW’s Mark Seidenberg. How does she feel? —- DPI Superintendent Underly: “I support Eliminating the Foundations of Reading (FORT)” Teacher Test […]

The Literacy View:

Podcast: Steve Dykstra’s Interpretation of Mark Seidenberg’s Slide Deck-Season 3 When I first started tutoring, I saw only BL casualties. I had thought that when local schools and districts switched to SOR, my tutoring practice would dry up. But that's not what happened. 1/x https://t.co/FyoaUNsmRR — Tisha Rajendra (@TishaRajendra) December 15, 2023

About the science in “The Science of Reading”

Mark Seidenberg: My heart sank. Why would a person need to ask this? The goal of teaching children to read is reading, not phonemic awareness. We know that learning to read does not require being able to identify 44 phonemes or demonstrate proficiency on phoneme deletion and substitution tasks because until very recently no one who learned […]

“Only 37% (of Wisconsin Students) were rated as “proficient” or “advanced.””

Akan Borsuk: Reading instruction, on the other hand, “is one thing we can do well. … We could do a lot better in the classroom,” Seidenberg said. The education establishment, he said, has been resistant to the notion that science around how letters on a page become understood in a child’s brain can help teachers. […]

DPI Testimony, Q&A Wisconsin Education Committee

Audio Transcript One of the line items in Wisconsin Motion 57 directly connects to our ED prep programs and reading. It states that Wisconsin will [00:11:00] contract with a vendor who will conduct an analysis of reading program coursework in our UW institutions. After engaging in our very robust and required state procurement process, the […]

Instructional Coach Kyle Thayse Wisconsin Education Committee Testimony; Q&A; Lucy Calkins

Transcript mp3 Audio Entire hearing video. An interesting excerpt, regarding their use of the discredited Lucy Caulkins Reading Curriculum (see Sold a Story): Senator John Jagler. Thank you. I, as I talked to, to my local administrators, [00:21:00] um, I’m fascinated. Curriculum choices that have been made and continue to be made. [00:21:06] And I’m, […]

3 Minutes: $pending, ED Schools & Reading Outcomes

Transcript: $pending, K-12 Governance, Ed Schools and Reading Outcomes [00:00:00] Senator Duey Stroebel: Actually looking at, uh, US census data, all funds, all sources. Um, Wisconsin’s at about $13,000 and Mississippi is about $9,200. So there’s significant that’s per the US census data, all funds, all sources. So pretty clear there. I think it’s, uh, […]

Kymyona Burk Appearance before the Joint Wisconsin Education Committee

Transcript mp3 audio www site Additional testimony: Mark Seidenberg Instructional Coach Kyle Thayse DPI 3 Minute Summary by Senator Duey Stroebel

Informational hearing on the subject of reading in Wisconsin schools March 2, 2023

Wisconsin Senate (and Assembly) Committee on Education: Department of Public Instruction Laura Adams -Policy Initiatives Advisor for the State Superintendent Duy Nguyen – Assistant Superintendent for the Division of Academic Excellence Tom McCarthy – Executive Director for the Office of the State Superintendent ExcelinEd Dr. Kymyona Burk – Senior Policy Fellow University of Wisconsin–Madison Mark […]

Notes on a recent Madison Early Literacy Summit

Scott Girard: “Most teachers are still learning how to teach reading from the commercial materials that they’re being supplied,” he said. “These materials are defective. What teachers have traditionally learned from them is poor practices. “What’s the effect? Some kids are going to learn to read anyway, but for a lot of children it makes […]

“The fact that she was disconnected from that research is evidence of the problem.” Madison….

Dana Goldstein: How Professor Calkins ended up influencing tens of millions of children is, in one sense, the story of education in America. Unlike many developed countries, the United States lacks a national curriculum or teacher-training standards. Local policies change constantly, as governors, school boards, mayors and superintendents flow in and out of jobs. Amid […]

Letter to Wisconsin Governor Evers on His Roadmap to Reading Success Veto

State Senator Kathy Bernier and State Representative Joel Kitchens: Literacy in Wisconsin is in crisis: 64% of Wisconsin 4th graders can’t read at grade level, with 34% failing to read at even the basic level. As co-chair of Governor Walker’s Read to Lead Task Force, you know that high quality universal literacy screening is the […]

Influential authors Fountas and Pinnell stand behind disproven reading theory

Emily Hanford and Christopher Peak Mark Seidenberg, a cognitive scientist at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who studies reading and language development, said this statement doesn’t square with what decades of scientific research has shown about how reading works. “If a child is reading ‘pony’ as ‘horse,’ these children haven’t been taught to read. And they’re […]

Clarity about Fountas and Pinnell

Mark Seidenberg: Fountas and Pinnell have written a series of blog posts defending their popular curriculum, which is being criticized as based on discredited ideas about how children learn to read. (See Emily Hanford’s post here; EdReports evaluation here, many comments in the blogosphere.) The question is why school systems should continue to invest in the F&P curriculum and […]

Reading Meetings

Mark Seidenberg: Reading researcher and author Dr. Mark Seidenbergtalks with people working to improve literacy outcomes in the US and other countries. Teachers, school system administrators, activists, parents—and readers!—confront the hard questions about how to address low literacy outcomes, especially among children with other risk factors, such as poverty and development conditions such as dyslexia. Dr. Molly […]

Education Schools & Dogma

For a research project 1.Which belief, currently deemed true by scientific consensus, is most important for teachers & faculty at schools of ed to know? 2.Which belief, currently deemed false by scientific consensus, is nevertheless often believed by Ts & faculty at schls of ed? — Daniel Willingham (@DTWillingham) December 15, 2020 2010: When A […]

Commentary on Madison’s long term, disastrous reading results: “Madison’s status quo tends to be very entrenched.”

Scott Girard: “The problem was we could not get the teachers to commit to the coaching.” Since their small success, not much has changed in the district’s overall results for teaching young students how to read. Ladson-Billings called the ongoing struggles “frustrating,” citing an inability to distinguish between what’s important and what’s a priority in […]

A Task force on Madison’s Long term, Disastrous Reading Results

.@MMSDschools and @UWMadEducation announce a 14-member early literacy task force focused on analyzing approaches to teaching reading “toward the goals of improving reading outcomes and reducing achievement gaps.” More details at a 1 p.m. press availability. Members: pic.twitter.com/mPDoVmDrTF — Scott Girard (@sgirard9) December 14, 2020 Yet, deja vu all around Madison’s long term, disastrous reading […]

“I don’t think that actually stating they’re supporting these policies actually means that anything will change” (DPI Teacher Mulligans continue)

Logan Wroge: “I don’t think that actually stating they’re supporting these policies actually means that anything will change,” said Mark Seidenberg, a UW-Madison psychology professor. “I don’t take their statement as anything more than an attempt to defuse some of the controversy and some of the criticism that’s being directed their way.” While there’s broad […]

Mission vs. Organization: Madison’s long term, disastrous reading results

This meeting was held at Lakeview public library. Asking attendees to leave would have been a violation of the Madison Public Library’s rules of use, which require that “meetings be free and open to the general public at all times.” pic.twitter.com/BRgxOnbSmk — Chan Stroman (@eduphilia) December 13, 2019 It was nonetheless made quite apparent that […]

This is why we don’t have better readers: Response to Lucy Calkins

Mark Seidenberg: Lucy Calkins has written a manifesto entitled “No One Gets To Own The Term ‘Science Of Reading’”. I am a scientist who studies reading. Her document is not about the science that I know; it is about Lucy Calkins. Ms. Calkins is a prolific pedagogical entrepreneur who has published numerous curricula and supporting […]

In Wisconsin Even Dyslexia Is Political

Mark Seidenberg Wisconsin legislators are considering an important issue: how to help dyslexic children who struggle to read. You might think that helping poor readers is something everyone could get behind, but no. Dyslexia was identified in the 1920s and has been studied all over the world. It affects about 15% of all children, runs […]

Commentary on madison high school “resource officers”

Negassi Tesfamichael: Under a newly proposed contract between the city and the Madison Metropolitan School District, MMSD has the ability to move away from having an officer in each of the city’s four high schools starting in the 2020-21 school year. Under the new language in the contract, MMSD would have until Sept. 15 to […]

Why are Madison’s Students Struggling to Read?

Jenny Peek: Mark Seidenberg, a UW-Madison professor and cognitive neuroscientist, has spent decades researching the way humans acquire language. He is blunt about Wisconsin’s schools’ ability to teach children to read: “If you want your kid to learn to read you can’t assume that the school’s going to take care of it. You have to […]

Hard Words: Why aren’t kids being taught to read? “The study found that teacher candidates in Mississippi were getting an average of 20 minutes of instruction in phonics over their entire two-year teacher preparation program”

Emily Hanford: Balanced literacy was a way to defuse the wars over reading,” said Mark Seidenberg, a cognitive neuroscientist and author of the book “Language at the Speed of Sight.” “It succeeded in keeping the science at bay, and it allowed things to continue as before.” He says the reading wars are over, and science […]

On Wisconsin’s (and Madison’s) Long Term, Disastrous Reading Results

Alan Borsuk: But consider a couple other things that happened in Massachusetts: Despite opposition, state officials stuck to the requirement. Teacher training programs adjusted curriculum and the percentage of students passing the test rose. A test for teachers In short, in Wisconsin, regulators and leaders of higher education teacher-prep programs are not so enthused about […]

Commentary on Wisconsin’s Reading Challenges

Alan Borsuk: Overall, the Read to Lead effort seems like the high water mark in efforts to improve how kids are taught reading in Wisconsin — and the water is much lower now. What do the chair and the vice-chair think? Efforts to talk to Walker were not successful. Evers said, “Clearly, I’m disappointed. . […]

Support modifications to the Wisconsin PI-34 educator licensing rule

Wisconsin Reading Coalition E-Alert: We have sent the following message and attachment to the members of the Joint Committee for Review of Administrative Rules, urging modifications to the proposed PI-34 educator licensing rule that will maintain the integrity of the statutory requirement that all new elementary, special education, and reading teachers, along with reading specialists, […]

Requesting action one more time on Wisconsin PI-34 teacher licensing

Wisconsin Reading Coalition, via a kind email: Thanks to everyone who contacted the legislature’s Joint Committee for Review of Administrative Rules (JCRAR) with concerns about the new teacher licensing rules drafted by DPI. As you know, PI-34 provides broad exemptions from the Wisconsin Foundations of Reading Test (FORT) that go way beyond providing flexibility for […]

Wisconsin DPI efforts to weaken the Foundations of Reading Test for elementary teachers

Wisconsin Reading Coalition, via a kind email: Wisconsin Reading Coalition has alerted you over the past 6 months to DPI’s intentions to change PI-34, the administrative rule that governs teacher licensing in Wisconsin. We consider those changes to allow overly-broad exemptions from the Wisconsin Foundations of Reading Test for new teachers. The revised PI-34 has […]

Wisconsin Reading Corp tutors combat literacy crisis one child at a time

Alan Borsuk: As someone recently put it to me, improving Wisconsin’s overall results in reading will not come from pushing one button. It will require pushing maybe 10 buttons. A lot needs to be done. Some of the buttons that should be pushed connect to what goes on in school. Some connect to things beyond […]

Governor Candidate & Wisconsin Public Instruction chief Tony Evers Governance Commentary (track record?)

Tony Evers: As state superintendent, I’ve fought Walker’s school privatization schemes. I’ve proudly stood by our educators and fought for more funding for our public schools, while Walker has cut funding. We must never forget that under Walker, over a million Wisconsinites voted to raise their own taxes to adequately fund their schools. This isn’t […]

Where is the outrage on Wisconsin‘s achievement gap? And Madison…

Alan Borsuk: There was not much reaction and certainly no surge of commitment and effort. Jump ahead to now. Everything that was true in 2004 remains true. NAEP scores come out generally every two years and a new round was released a few days ago. The scores for Wisconsin stayed generally flat and were unimpressive. […]

A new proposal for reforming teacher education

Daniel Willingham: What Should Teachers Know? Is my experience representative? Are most teachers unaware of the latest findings from basic science—in particular, psychology—about how children think and learn? Research is limited, but a 2006 study by Arthur Levine indicated that teachers were, for the most part, confident about their knowledge: 81 percent said they understood […]

Why American Students Haven’t Gotten Better at Reading in 20 Years

Natalie Wexler: Cognitive scientists have known for decades that simply mastering comprehension skills doesn’t ensure a young student will be able to apply them to whatever texts they’re confronted with on standardized tests and in their studies later in life. One of those cognitive scientists spoke on the Tuesday panel: Daniel Willingham, a psychology professor […]

Reading and Wisconsin Education “Administrative Rules”

Patrick Marley: A group of teachers and parents sued, arguing the law didn’t apply to Evers because of the powers granted to him by the state constitution. A Dane County judge agreed with them in 2012 and the state Supreme Court upheld that ruling in 2016. In 2017, Walker signed a new, similar law. Evers […]

Research to Practice Symposium on Reading Proficiency; March 12, 2018

AIM institute: Join us for this FREE unique professional experience! Hear from the experts, reflect on connections to your own work with students, and explore the benefits and challenges of bridging the gap between the latest literacy research and best practices in the classroom. Elsa Cárdenas-Hagan: Differentiated Language and Literacy Instruction for English Learners Mark […]

The Gap Between The Science On Kids And Reading, And How It Is Taught (Madison’s Long Term, Disastrous Reading Results)

Claudio Sanchez: Mark Seidenberg is not the first researcher to reach the stunning conclusion that only a third of the nation’s school children read at grade level. The reasons are numerous, but one that Seidenberg cites over and over again is this: The way kids are taught to read in school is disconnected from the […]

Blue Cell Dyslexia

Mark Seidenberg: An article about dyslexia appeared last week in the prestigious Proceedings of the Royal Society B (“The [British] Royal Society’s flagship biological research journal, dedicated to the fast publication and worldwide dissemination of high-quality research”). A week is a long time in blog-years, I know, but impact of the article is rippling far […]

Relaxing Wisconsin’s Weak K-12 Teacher Licensing Requirements; MTEL?

Molly Beck: A group of school officials, including state Superintendent Tony Evers, is asking lawmakers to address potential staffing shortages in Wisconsin schools by making the way teachers get licensed less complicated. The Leadership Group on School Staffing Challenges, created by Evers and Wisconsin Association of School District Administrators executive director Jon Bales, released last […]

Speed reading

Mark Seidenberg: THE LATE NORA Ephron famously felt badly about her neck, but that’s minor compared to how people feel about their reading. We think everyone else reads faster than we do, that we should be able to speed up, and that it would be a huge advantage if we could. You could read as […]

Wisconsin hopes to mirror Massachusetts’ test success for teaching reading

A second-grade teacher notices that one of her students lacks fluency when reading aloud. The first thing the teacher should do to help this student is assess whether the student also has difficulties with:

A. predicting

B. inferring

C. metacognition

D. decoding

Don’t worry if you’re not into metacognition. The correct answer is decoding — at least according to the people who put together the test teachers must pass in Massachusetts if they are going to teach children to read.

The Massachusetts test is about to become the Wisconsin test, a step that advocates see as important to increasing the quality of reading instruction statewide and, in the long term, raising the overall reading abilities of Wisconsin students. As for those who aren’t advocates (including some who are professors in schools of education), they are going along, sometimes with a more dubious attitude to what this will prove.

The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction officially launched the era of the new test for reading licenses with a memo sent last week to heads of all teacher preparation programs in the state. The memo spelled out the details of implementing a law passed in 2011 that called for Wisconsin to use the Massachusetts test. The memo included setting the passing score, which, after a short phase-in period, will match what is regarded as the demanding Massachusetts standard.

In a nutshell, after Jan. 31, 2014, anyone who wants to get a license that allows them to teach reading in Wisconsin will have to pass this test, with 100 multiple choice questions and two essay questions, aimed at making sure they are adequately prepared to do so. (Those currently licensed will not need to pass the test.)

Why Massachusetts? Because in the 1990s, Massachusetts launched initiatives, including requiring students to pass a high school graduation test, requiring teachers to pass licensure tests specific to the subjects they teach, and increasing spending on education, especially in schools serving low-income children.

At that point, Wisconsin and Massachusetts were pretty much tied, and down the list of states a bit, when it came to how students were doing. Within a few years, scores in Massachusetts rose significantly. The state has led the nation in fourth- and eighth-grade reading and math achievement for a decade. Wisconsin scores have stayed flat.Many notes and links on Wisconsin’s adoption of Massachusetts (MTEL) elementary English teacher content knowledge standards. UW-Madison Professor Mark Seidenberg’s recommended Wisconsin’s adoption of MTEL.

Continuing to Advocate Status Quo Governance & Spending (Outcomes?) in Madison

Madison School Board Member Ed Hughes:

First, I provide some background on the private school voucher imposition proposal. Next, I list thirteen ways in which the proposal and its advocates are hypocritical, inconsistent, irrational, or just plain wrong. Finally, I briefly explain for the benefit of Wisconsin Federation for Children why the students in Madison are not attending failing schools.

Related: Counterpoint by David Blaska.

Does the School Board Matter? Ed Hughes argues that experience does, but what about “Governance” and “Student Achievement”?

2005: When all third graders read at grade level or beyond by the end of the year, the achievement gap will be closed…and not beforeAccording to Mr. Rainwater, the place to look for evidence of a closing achievement gap is the comparison of the percentage of African American third graders who score at the lowest level of performance on statewide tests and the percentage of other racial groups scoring at that level. He says that, after accounting for income differences, there is no gap associated with race at the lowest level of achievement in reading. He made the same claim last year, telling the Wisconsin State Journal on September 24, 2004, “for those kids for whom an ability to read would prevent them from being successful, we’ve reduced that percentage very substantially, and basically, for all practical purposes, closed the gap”. Last Monday, he stated that the gap between percentages scoring at the lowest level “is the original gap” that the board set out to close.

Unfortunately, that is not the achievement gap that the board aimed to close.2009: 60% to 42%: Madison School District’s Reading Recovery Effectiveness Lags “National Average”: Administration seeks to continue its use. This program continues, despite the results.

2004: Madison Schools Distort Reading Data (2004) by Mark Seidenberg.

2012: Madison Mayor Paul Soglin: “We are not interested in the development of new charter schools”

Scott BauerAlmost half of Wisconsin residents say they haven’t heard enough about voucher schools to form an opinion, according to the Marquette University law school poll. Some 27 percent of respondents said they have a favorable view of voucher schools while 24 percent have an unfavorable view. But a full 43 percent said they hadn’t heard enough about them to form an opinion.

“There probably is still more room for political leadership on both sides to try to put forward convincing arguments and move opinion in their direction,” pollster Charles Franklin said.

The initial poll question about vouchers only asked for favorability perceptions without addressing what voucher schools are. In a follow-up question, respondents were told that vouchers are payments from the state using taxpayer money to fund parents’ choices of private or religious schools.

With that cue, 51 percent favored it in some form while 42 percent opposed it.

Walker is a staunch voucher supporter.More on the voucher proposal, here.

www.wisconsin2.org

A close observer of Madison’s $392,789,303 K-12 public school district ($14,547/student) for more than nine years, I find it difficult to see substantive change succeeding. And, I am an optimist.

It will be far better for us to address the District’s disastrous reading results locally, than to have change imposed from State or Federal litigation or legal changes. Or, perhaps a more diffused approach to redistributed state tax dollar spending.

Madison Mayor Soglin Commentary on our Local School Climate; Reading unmentioned

The city, he says, needs to help by providing kids with access to out-of-school programs in the evenings and during the summer. It needs to do more to fight hunger and address violence-induced trauma in children. And it needs to help parents get engaged in their kids’ education.

“We as a community, for all of the bragging about being so progressive, are way behind the rest of the nation in these areas,” he says.

The mayor’s stated plans for addressing those issues, however, are in their infancy.

Soglin says he is researching ways to get low-cost Internet access to the many households throughout the city that currently lack computers or broadband connections.

A serious effort to provide low-cost or even free Internet access to city residents is hampered by a 2003 state law that sought to discourage cities from setting up their own broadband networks. The bill, which was pushed by the telecommunications industry, forbids municipalities from funding a broadband system with taxpayer dollars; only subscriber fees can be used.

Ald. Scott Resnick, who runs a software company and plans to be involved in Soglin’s efforts, says the city will likely look to broker a deal with existing Internet providers, such as Charter or AT&T, and perhaps seek funding from private donors.Related: “We are not interested in the development of new charter schools” – Madison Mayor Paul Soglin.

Job one locally is to make sure all students can read.

Madison, 2004 Madison schools distort reading data by UW-Madison Professor Mark Seidenberg:Rainwater’s explanation also emphasized the fact that 80 percent of Madison children score at or above grade level. But the funds were targeted for students who do not score at these levels. Current practices are clearly not working for these children, and the Reading First funds would have supported activities designed to help them.

Madison’s reading curriculum undoubtedly works well in many settings. For whatever reasons, many chil dren at the five targeted schools had fallen seriously behind. It is not an indictment of the district to acknowledge that these children might have benefited from additional resources and intervention strategies.

In her column, Belmore also emphasized the 80 percent of the children who are doing well, but she provided additional statistics indicating that test scores are improving at the five target schools. Thus she argued that the best thing is to stick with the current program rather than use the Reading First money.

Belmore has provided a lesson in the selective use of statistics. It’s true that third grade reading scores improved at the schools between 1998 and 2004. However, at Hawthorne, scores have been flat (not improving) since 2000; at Glendale, flat since 2001; at Midvale/ Lincoln, flat since 2002; and at Orchard Ridge they have improved since 2002 – bringing them back to slightly higher than where they were in 2001.

In short, these schools are not making steady upward progress, at least as measured by this test.Madison, 2005: When all third graders read at grade level or beyond by the end of the year, the achievement gap will be closed…and not before by Ruth Robarts:

According to Mr. Rainwater, the place to look for evidence of a closing achievement gap is the comparison of the percentage of African American third graders who score at the lowest level of performance on statewide tests and the percentage of other racial groups scoring at that level. He says that, after accounting for income differences, there is no gap associated with race at the lowest level of achievement in reading. He made the same claim last year, telling the Wisconsin State Journal on September 24, 2004, “for those kids for whom an ability to read would prevent them from being successful, we’ve reduced that percentage very substantially, and basically, for all practical purposes, closed the gap”. Last Monday, he stated that the gap between percentages scoring at the lowest level “is the original gap” that the board set out to close.

Unfortunately, that is not the achievement gap that the board aimed to close.

In 1998, the Madison School Board adopted an important academic goal: “that all students complete the 3rd grade able to read at or beyond grade level”. We adopted this goal in response to recommendations from a citizen study group that believed that minority students who are not competent as readers by the end of the third grade fall behind in all academic areas after third grade.

“All students” meant all students. We promised to stop thinking in terms of average student achievement in reading. Instead, we would separately analyze the reading ability of students by subgroups. The subgroups included white, African American, Hispanic, Southeast Asian, and other Asian students.

“Able to read at or beyond grade level” meant scoring at the “proficient” or “advanced” level on the Wisconsin Reading Comprehension Test (WRC) administered during the third grade. “Proficient” scores were equated with being able to read at grade level. “Advanced” scores were equated with being able to read beyond grade level. The other possible scores on this statewide test (basic and minimal) were equated with reading below grade level.Madison, 2009: 60% to 42%: Madison School District’s Reading Recovery Effectiveness Lags “National Average”: Administration seeks to continue its use.

Madison, 2012: Madison’s “Achievement Gap Plan”:The other useful stat buried in the materials is on the second page 3 (= 6th page), showing that the 3rd grade proficiency rate for black students on WKCE, converted to NAEP-scale proficiency, is 6.8%, with the accountability plan targeting this percentage to increase to 23% over one school year. Not sure how this happens when the proficiency rate (by any measure) has been decreasing year over year for quite some time. Because the new DPI school report cards don’t present data on an aggregated basis district-wide nor disaggregated by income and ethnicity by grade level, the stats in the MMSD report are very useful, if one reads the fine print.

Does the School Board Matter? Ed Hughes argues that experience does, but what about “Governance” and “Student Achievement”?

Madison School Board Member Ed Hughes

Call me crazy, but I think a record of involvement in our schools is a prerequisite for a School Board member. Sitting at the Board table isn’t the place to be learning the names of our schools or our principals.

Wayne Strong, TJ Mertz and James Howard rise far above their opponents for those of us who value School Board members with a history of engagement in local educational issues and a demonstrated record of commitment to our Madison schools and the students we serve.Notes and links on Ed Hughes and the 2013 Madison School Board election.

I’ve become a broken record vis a vis Madison’s disastrous reading results. The District has been largely operating on auto-pilot for decades. It is as if a 1940’s/1950’s model is sufficient. Spending increases annually (at lower rates in recent years – roughly $15k/student), yet Madison’s disastrous reading results continue, apace.

Four links for your consideration.

When all third graders read at grade level or beyond by the end of the year, the achievement gap will be closed…and not beforeAccording to Mr. Rainwater, the place to look for evidence of a closing achievement gap is the comparison of the percentage of African American third graders who score at the lowest level of performance on statewide tests and the percentage of other racial groups scoring at that level. He says that, after accounting for income differences, there is no gap associated with race at the lowest level of achievement in reading. He made the same claim last year, telling the Wisconsin State Journal on September 24, 2004, “for those kids for whom an ability to read would prevent them from being successful, we’ve reduced that percentage very substantially, and basically, for all practical purposes, closed the gap”. Last Monday, he stated that the gap between percentages scoring at the lowest level “is the original gap” that the board set out to close.

Unfortunately, that is not the achievement gap that the board aimed to close.60% to 42%: Madison School District’s Reading Recovery Effectiveness Lags “National Average”: Administration seeks to continue its use. This program continues, despite the results.

3rd Grade Madison School District Reading Proficiency Data (“Achievement Gap Plan”)The other useful stat buried in the materials is on the second page 3 (= 6th page), showing that the 3rd grade proficiency rate for black students on WKCE, converted to NAEP-scale proficiency, is 6.8%, with the accountability plan targeting this percentage to increase to 23% over one school year. Not sure how this happens when the proficiency rate (by any measure) has been decreasing year over year for quite some time. Because the new DPI school report cards don’t present data on an aggregated basis district-wide nor disaggregated by income and ethnicity by grade level, the stats in the MMSD report are very useful, if one reads the fine print.

Madison Schools Distort Reading Data (2004) by Mark Seidenberg.

How many School Board elections, meetings, votes have taken place since 2005 (a number of candidates were elected unopposed)? How many Superintendents have been hired, retired or moved? Yet, the core structure remains. This, in my view is why we have seen the move to a more diffused governance model in many communities with charters, vouchers and online options.

Change is surely coming. Ideally, Madison should drive this rather than State or Federal requirements. I suspect it will be the latter, in the end, that opens up our monolithic, we know best approach to public education.

The science and politics of reading instruction

Just out: Mark Seidenberg, “Politics (of Reading) Makes Strange Bedfellows”, Perspectives on Language and Literacy, Summer 2012. The article’s opening explains the background:

In 2011, Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker created the Read to Lead Task Force to develop strategies for improving literacy. Like many states, Wisconsin has a literacy problem: 62% of the eighth grade students scoring at the Basic or Below Basic levels on the 2011 NAEP; large discrepancies between scores on the NAEP and on the state’s homegrown reading assessment; and a failing public school system in the state’s largest city, Milwaukee. The task force was diverse, including Democratic and Republican state legislators, the head of the Department of Public Instruction, classroom teachers, representatives of several advocacy groups, and the governor himself. I was invited to speak at the last of their six meetings. I had serious misgivings about participating. Under the governor’s controversial leadership, collective bargaining rights for teachers and other public service employees were eliminated and massive cuts to public education enacted. As a scientist who has studied reading for many years and followed educational issues closely I decided to use my 10 minutes to speak frankly. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of my remarks.

From the beginning of those remarks:Much more on Mark Seidenberg, here.

Monkey See, Monkey Do. Monkey Read?

Erin Loury, via a kind reader:

Monkeys banging on typewriters might never reproduce the works of Shakespeare, but they may be closer to reading Hamlet than we thought. Scientists have trained baboons to distinguish English words from similar-looking nonsense words by recognizing common arrangements of letters. The findings indicate that visual word recognition, the most basic step of reading, can be learned without any knowledge of spoken language.

The study builds on the idea that when humans read, our brains first have to recognize individual letters, as well as their order. “We’re actually reading words much like we identify any kind of visual object, like we identify chairs and tables,” says study author Jonathan Grainger, a cognitive psychologist at France’s National Center for Scientific Research, and Aix-Marseille University in Marseille, France. Our brains construct words from an assembly of letters like they recognize tables as a surface connected to four legs, Grainger says.Mark Seidenberg emails:

here’s what you need to know:

http://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=3912

Basically, the study shows nothing of any interest about reading. it shows that baboons could pick up on differences in letter frequencies between word and nonword stimuli that allowed to tell them apart about 75% of the time.

This is trivial compared to what a reader knows about the properties of written English.

the paper is here:

https://www.sciencemag.org/content/336/6078/245.full

Wisconsin Framework for Educator (Teacher) Effectiveness

Design Team Report & Recommendation:1. Guiding Principles

The Design Team believes that the successful development and implementation of the new performance-based evaluation system is dependent upon the following guiding principles,

which define the central focus of the entire evaluation system. The guiding principles of the educator evaluation system are:

The ultimate goal of education is student learning. Effective educators are essential to achieving that goal for all students. We believe it is imperative that students have highly effective teams of educators to support them throughout their public education. We further believe that effective practice leading to better educational achievement requires continuous improvement and monitoring.

A strong evaluation system for educators is designed to provide information that supports decisions intended to ensure continuous individual and system effectiveness. The system must be well-articulated, manageableRelated: Wisconsin 25th in 2011 NAEP Reading, Comparing Rhetoric Regarding Texas (10th) & Wisconsin NAEP Scores: Texas Hispanic and African-American students rank second on eighth-grade NAEP math test, Wisconsin, Mississippi Have “Easy State K-12 Exams” – NY Times and Seidenberg endorses using the Massachusetts model exam for teachers of reading (MTEL 90), which was developed with input from reading scientists. He also supports universal assessment to identify students who are at risk, and he mentioned the Minnesota Reading Corps as a model of reading tutoring that would be good to bring to Wisconsin.

9.27.2011 Wisconsin Read to Lead Task Force Notes

Wisconsin Reading Coalition, via a kind Chan Stroman-Roll email:

Guest Speaker Mark Seidenberg (Donald O. Hebb and Hilldale Professor of Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience, UW-Madison): Professor Seidenberg gave an excellent presentation on the science of reading and why it is important to incorporate the findings of that science in teaching. Right now there is a huge disconnect between the vast, converged body of science worldwide and instructional practice. Prospective teachers are not learning about reading science in IHE’s, and relying on intuition about how to teach reading is biased and can mislead. Teaching older students to read is expensive and difficult. Up-front prevention of reading failure is important, and research shows us it is possible, even for dyslexic students. This will save money, and make the road easier for students to learn and teachers to teach. Seidenberg endorses using the Massachusetts model exam for teachers of reading (MTEL 90), which was developed with input from reading scientists. He also supports universal assessment to identify students who are at risk, and he mentioned the Minnesota Reading Corps as a model of reading tutoring that would be good to bring to Wisconsin.

Lander: Can Seidenberg provide a few examples of things on which the Task Force could reach consensus?

Seidenberg: There is a window for teaching basic reading skills that then will allow the child to move on to comprehension. The balanced literacy concept is in conflict with best practices. Classrooms in Wisconsin are too laissez-faire, and the spiraling approach to learning does not align with science.

Michael Brickman: Brickman, the Governor’s aide, cut off the discussion with Professor Seidenberg, and said he would be in touch with him later.Much more on the Read to Lead Task Force, here.

A Capitol Conversation on Wisconsin’s Reading Challenges

UW-Madison Professor Mark Seidenberg and I had an informative conversation with two elected officials at the Capitol recently.

I am thankful for Mark’s time and the fact that both Luther Olsen and Steve Kestell along with staff members took the time to meet. I also met recently with Brett Hulsey and hope to meet with more elected officials, from both parties.

The topic du jour was education, specifically the Governor’s Read to Lead task force.

Mark kindly shared this handout:My name is Mark Seidenberg, Hilldale Professor and Donald O. Hebb Professor, Department of Psychology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, seidenberg@wisc.edu, http://lcnl.wisc.edu. I have studied how reading works, how children learn to read, reading disabilities, and the brain bases of reading for over 30 years. I am a co-author of a forthcoming report from the National Research Council (National Academy of Sciences) on low literacy among older adolescents and adults. I’m writing a general audience book about reading research and educational practices.

We have a literacy problem: about 30% of the US (and WI) population reads at a “basic” or “below basic” level. Literacy levels are particularly low among poor and minority individuals. The identification of this problem does not rest on any single test (e.g., NAEP, WKCE, OECD). Our literacy problem arises from many causes, some of which are not easy to address by legislative fiat. However, far more could be done in several important areas.

1. How teachers are taught. In Wisconsin as in much of the US, prospective teachers are not exposed to modern research on how children develop, learn, and think. Instead, they are immersed in the views of educational theorists such as Lev Vygotsky (d. 1934) and John Dewey (d. 1952). Talented, highly motivated prospective teachers are socialized into beliefs about children that are not informed by the past 50 years of basic research in cognitive science and cognitive neuroscience.

A vast amount is known about reading in particular, ranging from what your eyes do while reading to how people comprehend documents to what causes reading disabilities. However, there is a gulf between Education and Science, and so this research is largely ignored in teacher training and curriculum development.

2. How children are taught. There continue to be fruitless battles over how beginning readers should be taught, and how to insure that comprehension skills continue to develop through middle and high school. Teachers rely on outdated beliefs about how children learn, and how reading works. As a result, for many children, learning to read is harder than it should be. We lose many children because of how they are taught. This problem does NOT arise from “bad teachers”; there is a general, systematic problem related to teacher education and training in the US.

3. Identification of children at risk for reading failures. Some children are at risk for reading and school failure because of developmental conditions that interfere with learning to read. Such children can be identified at young ages (preschool, kindergarten) using relatively simple behavioral measures. They can also be helped by effective early interventions that target basic components of reading such as vocabulary and letter-sound knowledge. The 30% of the US population that cannot read adequately includes a large number of individuals whose reading/learning impairments were undiagnosed and untreated.

Recommendations: Improve teacher education. Mechanism: change the certification requirements for new teachers, as has been done in several other states. Certification exams must reflect the kinds of knowledge that teachers need, including relevant research findings from cognitive science and neuroscience. Instruction in these areas would then need to be provided by schools of education or via other channels. In-service training courses could be provided for current teachers (e.g., as on-line courses).

Children who are at risk for reading and schooling failures must be identified and supported at young ages. Although it is difficult to definitively confirm a reading/learning disability in children at young ages (e.g., 4-6) using behavioral, neuroimaging, or genetic measures, it is possible to identify children at risk, most of whom will develop reading difficulties unless intervention occurs, via screening that involves simple tests of pre-reading skills and spoken language plus other indicators. Few children just “grow out of” reading impairments; active intervention is required.I am cautiously optimistic that we may see an improvement in Wisconsin’s K-12 curricular standards.

Related: Excellence in Education explains Florida’s reading reforms and compares Florida’s NAEP progress with Wisconsin’s at the July 29th Read to Lead task force meeting and www.wisconsin2.org.

Time for a Wisconsin Reading War….

Start the war.

What about Wisconsin? Wisconsin kids overall came in at the U.S. average on the NAEP scores. But Wisconsin’s position has been slipping. Many other states have higher overall scores and improving scores, while Wisconsin scores have stayed flat.

Steven Dykstra of the Wisconsin Reading Coalition, an organization that advocates for phonics programs, points out something that should give us pause: If you break down the new fourth-grade reading data by race and ethnic grouping, as well as by economic standing (kids who get free or reduced price meals and kids who don’t), Wisconsin kids trail the nation in every category. The differences are not significant in some, but even white students from Wisconsin score below the national average for white children.

(So how does Wisconsin overall still tie the national average? To be candid, the answer is because Wisconsin has a higher percentage of white students, the group that scores the highest, than many other states.)

Start the war.Related: Reading Recovery, Madison School Board member suggests cuts to Reading Recovery spending, UW-Madison Professor Mark Seidenberg on the Madison School District’s distortion of reading data & phonics and Norm and Dolores Mishelow Presentation on Milwaukee’s Successful Reading Program.

Milwaukee’s Plans for a One Size Fits All Reading Curriculum

The textbooks and the workbooks and the teachers manuals and all the other materials were displayed attractively. There were mini-candy bars and cloth shopping bags for visitors to take.

America’s biggest text book companies – Pearson, McGraw-Hill and Houghton-Mifflin Harcourt – each had large, handsome displays.

For three days last week, the third-floor library of the Juneau High School building was the center of looming big change in the way children in Milwaukee Public Schools are taught reading. MPS officials are selecting a new reading program.

A special committee will make a recommendation and the School Board will make the choice in the winner-takes-all curriculum selection process. The sunlit scene in the Juneau library was the part of the process where anyone could take a look and give input.

It was an amiable scene. The representatives of the publishers were friendly, talkative, knowledgeable, and quite willing to schmooze. “Great tie,” one told me as I walked down the aisle. She appeared to know something about this tie that no one else had noticed in the 20 years I’ve owned it.University of Wisconsin-Madison Psychology Professor Mark Seidenberg has written a number of articles on Madison’s reading programs.

60% to 42%: Madison School District’s Reading Recovery Effectiveness Lags “National Average”: Administration seeks to continue its use

via a kind reader’s email: Sue Abplanalp, Assistant Superintendent for Elementary Education, Lisa Wachtel, Executive Director, Teaching & Learning, Mary Jo Ziegler, Language Arts/Reading Coordinator, Teaching & Learning, Jennie Allen, Title I, Ellie Schneider, Reading Recovery Teacher Leader [2.6MB PDF]:

Background The Board of Education requested a thorough and neutral review of the Madison Metropolitan School District’s (MMSD) Reading Recovery program, In response to the Board request, this packet contains a review of Reading Recovery and related research, Madison Metropolitan School District (MMSD) Reading Recovery student data analysis, and a matrix summarizing three options for improving early literacy intervention. Below please find a summary of the comprehensive research contained in the Board of Education packet. It is our intent to provide the Board of Education with the research and data analysis in order to facilitate discussion and action toward improved effectiveness of early literacy instruction in MMSD.

Reading Recovery Program Description The Reading Recovery Program is an intensive literacy intervention program based on the work of Dr. Marie Clay in New Zealand in the 1970’s, Reading Recovery is a short-term, intensive literacy intervention for the lowest performing first grade students. Reading Recovery serves two purposes, First, it accelerates the literacy learning of our most at-risk first graders, thus narrowing the achievement gap. Second, it identifies children who may need a long-term intervention, offering systematic observation and analysis to support recommendations for further action.

The Reading Recovery program consists of an approximately 20-week intervention period of one-to-one support from a highly trained Reading Recovery teacher. This Reading Recovery instruction is in addition to classroom literacy instruction delivered by the classroom teacher during the 90-minute literacy block. The program goal is to provide the lowest performing first grade students with effective reading and writing strategies allowing the child to perform within the average range of a typical first grade classroom after a successful intervention period. A successful intervention period allows the child to be “discontinued” from the Reading Recovery program and to function proficiently in regular classroom literacy instruction.

Reading Recovery Program Improvement Efforts The national Reading Recovery data reports the discontinued rate for first grade students at 60%. In 2008-09, the discontinued rate for MMSD students was 42% of the students who received Reading Recovery. The Madison Metropolitan School District has conducted extensive reviews of Reading Recovery every three to four years. In an effort to increase the discontinued rate of Reading Recovery students, MMSD worked to improve the program’s success through three phases.Reading recovery will be discussed at Monday evening’s Madison School Board meeting.

Related:

- University of Wisconsin-Madison Psychology Professor Mark Seidenberg: Madison schools distort reading data:

In her column, Belmore also emphasized the 80 percent of the children who are doing well, but she provided additional statistics indicating that test scores are improving at the five target schools. Thus she argued that the best thing is to stick with the current program rather than use the Reading First money.

Belmore has provided a lesson in the selective use of statistics. It’s true that third grade reading scores improved at the schools between 1998 and 2004. However, at Hawthorne, scores have been flat (not improving) since 2000; at Glendale, flat since 2001; at Midvale/ Lincoln, flat since 2002; and at Orchard Ridge they have improved since 2002 – bringing them back to slightly higher than where they were in 2001.

In short, these schools are not making steady upward progress, at least as measured by this test.

Belmore’s attitude is that the current program is working at these schools and that the percentage of advanced/proficient readers will eventually reach the districtwide success level. But what happens to the children who have reading problems now? The school district seems to be writing them off.

So why did the school district give the money back? Belmore provided a clue when she said that continuing to take part in the program would mean incrementally ceding control over how reading is taught in Madison’s schools (Capital Times, Oct 16). In other words, Reading First is a push down the slippery slope toward federal control over public education.- Jeff Henriques references a Seidenberg paper on the importance of phonics, published in Psychology Review.

- Ruth Robarts letter to Isthmus on the Madison School District’s reading progress:

Thanks to Jason Shepard for highlighting comments of UW Psychology Professor Mark Seidenberg at the Dec. 13 Madison School Board meeting in his article, Not all good news on reading. Dr. Seidenberg asked important questions following the administrations presentation on the reading program. One question was whether the district should measure the effectiveness of its reading program by the percentages of third-graders scoring at proficient or advanced on the Wisconsin Reading Comprehension Test (WRCT). He suggested that the scores may be improving because the tests arent that rigorous.

I have reflected on his comment and decided that he is correct.

Using success on the WRCT as our measurement of student achievement likely overstates the reading skills of our students. The WRCT—like the Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Examination (WKCE) given in major subject areas in fourth, eighth and tenth grades— measures student performance against standards developed in Wisconsin. The more teaching in Wisconsin schools aims at success on the WRCT or WKCE, the more likely it is that student scores will improve. If the tests provide an accurate, objective assessment of reading skills, then rising percentages of students who score at the proficient and advanced levels would mean that more children are reaching desirable reading competence.- Madison teacher Barb Williams letter to Isthmus on Madison School District reading scores:

I’m glad Jason Shepard questions MMSD’s public display of self-congratulation over third grade reading test scores. It isn’t that MMSD ought not be proud of progress made as measured by fewer African American students testing at the basic and minimal levels. But there is still a sigificant gap between white students and students of color–a fact easily lost in the headlines. Balanced Literacy, the district’s preferred approach to reading instruction, works well for most kids. Yet there are kids who would do a lot better in a program that emphasizes explicit phonics instruction, like the one offered at Lapham and in some special education classrooms. Kids (arguably too many) are referred to special education because they have not learned to read with balanced literacy and are not lucky enough to land in the extraordinarily expensive Reading Recovery program that serves a very small number of students in one-on-on instruction. (I have witnessed Reading Recovery teachers reject children from their program because they would not receive the necessary support from home.)

Though the scripted lessons typical of most direct instruction programs are offensive to many teachers (and is one reason given that the district rejected the Reading First grant) the irony is that an elementary science program (Foss) that the district is now pushing is also scripted as is Reading Recovery and Everyday Math, all elementary curricula blessed by the district.

I wonder if we might close the achievement gap further if teachers in the district were encouraged to use an approach to reading that emphasizes explicit and systematic phonics instruction for those kids who need it. Maybe we’d have fewer kids in special education and more children of color scoring in the proficient and advanced levels of the third grade reading test.

Milwaukee Public Schools needs to pick up the pace in reading

Maybe this is the biggest problem facing Milwaukee Public Schools: A panel of national experts ripped reading programs overall in the city, saying they were ineffective, out of date, uncoordinated, led by teachers who were inadequately prepared and who were really doing nothing much to help struggling readers.

Maybe this is the biggest problem facing MPS: That report came nine months ago and the in-the-classroom response so far has been to set four priorities for this school year of breathtaking modesty. Maybe a year from now, there will be big changes, officials say.

We’re talking about reading. Reading. The core skill for success in just about any part of education and in life beyond school. A sore point for MPS for at least a couple decades. Last year, 40% of MPS 10th-graders rated as proficient in reading in state tests, a number in line with a string of prior years.

“The status quo will need to be changed – sometimes dramatically,” said the report from a three-person review team brought in by the state Department of Public Instruction as part of its efforts under federal law to push change in MPS. The report was issued last December, calling for an overhaul of the way reading is taught in MPS – the curriculum used, the way teachers are trained, the way the whole subject is handled from top to bottom.

Since then, an MPS work group was named. The work group got an extension on the time it had to give a draft plan to the DPI. The draft plan was submitted. DPI officials gave some feedback. MPS officials revised their plan. DPI officials took awhile to respond with requests for more changes. It’s late September now. A plan has not been approved. There’s a meeting scheduled in early October.Related:

- When all third graders read at grade level or beyond by the end of the year, the achievement gap will be closed…and not before by Ruth Robarts

- Madison schools distort reading data by Mark Seidenberg

- Shameful reading scores for MMSD Sophomores by Ed Blume.

Bellevue, WA Teacher Strike: District Offers Teachers a 5% Raise over 3 Years

The Bellevue School District increased its salary offer to teachers in a late-night bargaining session Thursday.

The total pay raise would be 5 percent over the three-year contract.

Union officials praised the move and said they planned to hold an “optimism” rally at Crossroads Park in Bellevue today while bargaining was expected to continue.

“It’s a move in the right direction,” said Michele Miller, Bellevue Education Association president.

The school district initially offered teachers 3 percent in wage increases over the three-year contract but raised the offer to 4.5 percent last week, saying the increase was contingent on voter approval of a levy in the third year of the contract.Bellevue, WA Teacher Salary Schedule with 2008-2009 District Offer: 16k PDF

Curriculum is also an issue in this strike [32K PDF]:Language Arts 4th – 12th grade: Many teachers believe there far too few lessons on punctuation and grammar. You cannot add lessons in these areas, since that might supplant the scripted lesson goal of the day.

Middle School Math: Since the district only allows one level of math at each grade in Middle School, there are many bored and overwhelmed students simultaneously stuck in the same class. The District’s current curriculum proposal wouldn’t allow a teacher to develop entirely new topics of instruction to engage the bored students. Additionally, while teachers would be allowed to make small adjustments for struggling kids, they couldn’t use those changes the following year without the approval of the Curriculum Department.

Certainly, Math and writing skills are fertile ground for curriculum controversy.

I asked Madison’s three superintendent candidates earlier this year if they supported a “top down” curricular approach or, simply hiring the best teachers. It’s hard to imagine a top down approach actually working in a large organization.

Madison School District Administration’s Proposed 2008-2009 Budget Published

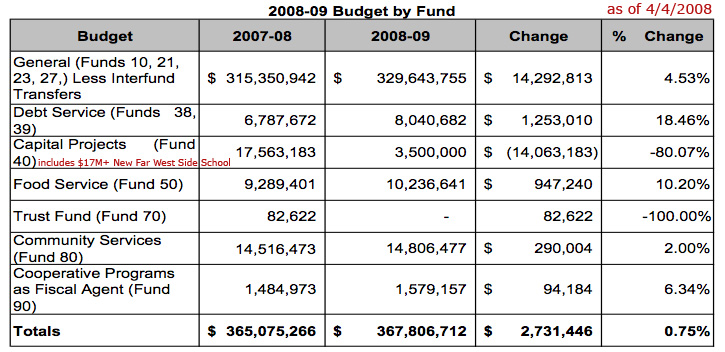

The observation of school district budgeting can be fascinating. Numbers are big (9 or more digits) and the politics often significant. Many factors affect such expenditures including, local property taxes, state and federal redistributed tax dollars, enrollment, grants, referendums, new programs, politics and periodically, local priorities. The Madison School District Administration released it’s proposed 2008-2009 $367,806,712 budget Friday, April 4, 2008.

There will be a number of versions between now and sometime next year. The numbers will change.

Allocations were sent to the schools on March 5, 2008 prior to the budget’s public release. MMSD 2008-2009 Budget timeline.

I’ve summarized budget and enrollment information from1995 through 2008-2009 below:

“Cooking the Numbers” – Madison’s Reading Program

Joanne Jacobs: From the Fayetteville, NC Observer: Superintendent Art Rainwater loves to discuss the Madison Metropolitan School District’s success in eliminating the racial achievement gap. But he won’t consult with educators from other communities until they are ready to confront the issue head on. “I’m willing to talk,” Rainwater tells people seeking his advice, “when […]

More on Madison’s Reading First Rejection and Reading Recovery

Joanne Jacobs: Reading War II is still raging as reading experts attack a New York Times story on Madison’s decision to reject federal Reading First funds in order to continue a reading program that the Times claims is effective. Education News prints as-yet unpublished letters to the Times from Reid Lyons, Robert Sweet, Louisa Moats, […]

Madison’s Reading Battle Makes the NYT: In War Over Teaching Reading, a U.S.-Local Clash

Diana Jean Schemo has been at this article for awhile: The program, which gives $1 billion a year in grants to states, was supposed to end the so-called reading wars — the battle over the best method of teaching reading — but has instead opened a new and bitter front in the fight. According to […]

ED.Gov: New Report Shows Progress in Reading First Implementation and Changes in Reading Instruction

US Department of Education: Children in Reading First classrooms receive significantly more reading instruction and schools participating in the program are much more likely to have a reading coach, according to the Reading First Implementation Evaluation: Interim Report, released today by the U.S. Department of Education. The report shows significant differences between what Reading First […]

FORUM: Abuses and Uses of Curriculum in the Area of Language & Reading

Video | MP3 Audio Rafael Gomez recently organized a Forum on: Abuses and Uses of Curriculum in the Area of Language & Reading: Participants included: Albert Watson: Project Bootstrape (sp?) Mark Seidenberg Dr. Paul Yvarra

2005 NAEP Results

2005 National and State Mathematics and Reading Assessments for grades 4 and 8 are now available. Robert Tomsho takes a look at the reading results: Observers say boosting reading scores isn’t likely to get any easier, given the rapidly changing demographics in the nation’s schools where, for many students, English is a second language. Indeed, […]

UW Center Established To Promote Reading Recovery

A gift of nearly $3 million is being used to boost teacher training at the UW-Madison in a special, reading program. But that program, Reading Recovery, has critics, who say it’s not worth the necessary investment. Training at a new UW-Madison Reading Recovery Center will involve videotaping teachers, as they instruct young children, in a […]

A Few Notes on the Superintendent’s Evaluation & Curriculum

Several writers have mentioned the positive news that the Madison Board of Education has reviewed Superintendent Art Rainwater for the first time since 2002. I agree that it is a step in the right direction. In my view, the first responsibility of the Board and Administration, including the Superintendent is curriculum: Is the Madison School […]

Third Grade Reading Scores

Madison third graders rank BELOW the state-wide average for children in the advanced and proficient categories. Nearly one-third of the African-American third graders read at basic or below. (And basic is below grade level.) African-American third grades still trail white students by a substantial margin. Schools at the bottom in 1978-79 are still at the […]

Study spells out new evidence for roots of dyslexia

Study spells out new evidence for roots of dyslexia (Posted by University Communications: 5/31/2005) Report of newly released research by Mark Seidenberg and colleagues. Addressing a persistent debate in the field of dyslexia research, scientists at UW-Madison and the University of Southern California (USC) have disproved the popular theory that deficits in certain visual processes […]

There�s something deeply wrong here.

In a letter to the editor of Isthmus UW Psychology Professor Mark Seidenberg wrote, “There�s something deeply wrong here. The educational establishment has embraced methods for teaching reading that have a weak scientific basis and are counterproductive for many beginning readers. They then develop a very expensive remedial reading program to fix the problems created […]

Ruth Robarts Letter to the Isthmus editor on MMSD Reading Progress

Ruth Robarts wrote:

Thanks to Jason Shepard for highlighting comments of UW Psychology Professor Mark Seidenberg at the Dec. 13 Madison School Board meeting in his article, Not all good news on reading. Dr. Seidenberg asked important questions following the administrations presentation on the reading program. One question was whether the district should measure the effectiveness of its reading program by the percentages of third-graders scoring at proficient or advanced on the Wisconsin Reading Comprehension Test (WRCT). He suggested that the scores may be improving because the tests arent that rigorous.

I have reflected on his comment and decided that he is correct.

Using success on the WRCT as our measurement of student achievement likely overstates the reading skills of our students. The WRCT—like the Wisconsin Knowledge and Concepts Examination (WKCE) given in major subject areas in fourth, eighth and tenth grades— measures student performance against standards developed in Wisconsin. The more teaching in Wisconsin schools aims at success on the WRCT or WKCE, the more likely it is that student scores will improve. If the tests provide an accurate, objective assessment of reading skills, then rising percentages of students who score at the proficient and advanced levels would mean that more children are reaching desirable reading competence.

However, there are reasons to doubt that high percentages of students scoring at these levels on the WRCT mean that high percentages of students are very proficient readers. High scores on Wisconsin tests do not correlate with high scores on the more rigorous National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) tests.

In 2003, 80% of Wisconsin fourth graders scored proficient or advanced on the WCKE in reading. However, in the same year only 33% of Wisconsin fourth graders reached the proficient or advanced level in reading on the NAEP. Because the performance of Madison students on the WCKE reading tests mirrors the performance of students statewide, it is reasonable to conclude that many of Madisons proficient and advanced readers would also score much lower on the NAEP. For more information about the gap between scores on the WKCE and the NAEP in reading and math, see EdWatch Online 2004 State Summary Reports at www.edtrust.org.

Next year the federal No Child Left Behind Act replaces the Wisconsin subject area tests with national tests. In view of this change and questions about the value of WRCT scores, its time for the Board of Education to review its benchmarks for progress on its goal of all third-graders reading at grade level by the end of third grade.

Ruth Robarts

Member, Madison Board of Education

Madison schools distort reading data

U.W. psychologist, Mark Seidenberg, wrote an editorial in Sunday’s (12/12/04) edition of the Wisconsin State Journal critical of the way that the district is presenting its reading data. He also points out that although Superintendent Rainwater would like the public to believe “that accepting the Reading First funds would have required him to “eliminate” the […]

The Importance of Phonics

Relevant to the sucess of students at Marquette Elementary School, U.W. Psychologist Mark Seidenberg has a new paper in Psychological Review that shows that phonics is critical for skilled reading. Seidenberg’s research “suggests that teaching young children the relationships between spellings and sounds – or phonics – not only makes learning to read easier, but […]