Sex differences in sports performances continue to attract considerable scientific and public attention, driven in part by high profile cases of: 1) biological male (XY) athletes who seek to compete in the female category after gender transition, and 2) XY athletes with medical syndromes collectively known as disorders or differences of sex development (DSDs). In this perspective, we highlight scientific evidence that informs eligibility criteria and applicable regulations for sex categories in sports. There are profound sex differences in human performance in athletic events determined by strength, speed, power, endurance, and body size such that males outperform females. These sex differences in athletic performance exist before puberty and increase dramatically as puberty progresses. The profound sex differences in sports performance are primarily attributable to the direct and indirect effects of sex-steroid hormones and provide a compelling framework to consider for policy decisions to safeguard fairness and inclusion in sports.

Teacher sues Oakland School for the Arts for millions after firing

“It was like everyone assumed he had done it,” said Kris Bradburn, an Oakland School for the Arts teacher from 2008 to 2022. The accusation “was like touching the third rail on BART — you’re just like dead. There’s no coming back from it.”

Taylor’s story made headlines at a critical moment.

California schools, churches and Boy Scout groups were facing a wave of lawsuits after a 2019 law that expanded the statute of limitations to include decades-old sexual abuse.

At the same time, students across the Bay Area, including those at Oakland School for the Arts, or OSA, staged walkouts and other protests in response to claims of widespread and unaddressed sexual harassment on campuses.

But then, much more slowly and quietly, the case against Taylor fell apart.

k-12 Tax & $pending climate: The tech stampede from Seattle continues. What’s left? UW, with almost as many employees as students.

Amazon hasn’t pursued future development in the city since its public spat with the City Council over a short-lived per-employee tax in 2018. Instead, it shifted its growth to Bellevue and Redmond, dubbing the entire Puget Sound region as its HQ1. The company has more than 14,000 employees in Bellevue, according to the city’s latest financial report.

Growth aside, Amazon’s workforce in Seattle has been shaped by other factors since its peak during the pandemic.

As the pandemic waned and workers continued to stay home, Amazon and other tech companies seriously reconsidered their space needs. While Microsoft was moving out of office towers in Bellevue, Amazon was mirroring those actions in Seattle. Since 2020, Amazon has left at least six office buildings near its headquarters, totaling about 1 million square feet.

Amazon’s shrinking office footprint

Since 2020, Amazon has vacated six leased offices in the South Lake Union and Denny Triangle neighborhoods. It plans to leave a seventh office in May when the lease expires.

The company has also gone through massive waves of layoffs since 2020, the most recent of which affected about 3,300 employees in Seattle between October and January.

——-

Trivia: Amazon is no longer Seattle’s biggest employer.

State taxpayer-funded University of Washington (UW) now is.

Notes on the Rise of China’s Universities

Eleanor Alcott, Humza Jiliani and Andrew Jack:

Some of this research has translated into technological breakthroughs that have turbocharged Chinese industrial competitiveness — from labs that developed powerful battery technologies later used by leading companies in the electric vehicle sector, including CATL and BYD, to biotech companies such as BGI Genomics, which originated as a government-funded research institute working on human genomics.

As China has climbed the rankings, many critics have pointed to the industrial scale of fraudulent or poor-quality research, driven in part by incentives that reward publication volume in tenure and promotion decisions. Even metrics designed to measure a piece of research’s impact, such as citations, have at times been distorted by Chinese-authored papers being unnecessarily cited by fellow academics to boost their rating.

Ivan Oransky, co-founder of Retraction Watch, which tracks publication trends, says: “China’s government has been intensively gaming those metrics using incentives that have led to widespread misconduct, including paper mill activity.” Paper mills are companies paid to create fake academic studies.

In 2024, he recorded nearly 3,000 retractions of Chinese-authored papers from journals, compared with 177 for US authors.

But Bethany Allen, head of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute’s China investigations programme, cautions against dismissing Chinese universities by focusing on the volume of low-quality papers.

The plot to replace teachers with tech

When the professional breaking point came for public middle-school teacher Benjamin Coleman, it wasn’t about lousy pay, meddling helicopter parents, or even the insidiously distracting smartphones. It was a school-mandated computer program that had hijacked his classroom — and ultimately drove him toward early retirement.

For 10 years, Coleman loved his job teaching math and technology in Fall River, Mass. He lived for the “teachable moments” when young minds lit up and grasped concepts during lively, spontaneous tangents from lesson plans. Then his district mandated that he use i-Ready, an online platform that delivers canned tests and “personalized learning” on internet-connected devices. Coleman wasn’t wild about it. His students began complaining bitterly. Many disengaged entirely or learned to game the system.

Then a directive came down that usage of the system would increase. “The day that the principal told us that we needed to do i-Ready three times a week, that’s when I was done,” he tells me. “It was three hours a week for each class, when we only had five hours a week. So 60% of the teaching was going to be done by this computer that the kids absolutely hate. That’s not what I went to college for.”

Coleman’s story isn’t unusual. Across the United States, veteran teachers in public and private schools alike describe a quiet exodus from a profession radically transformed by i-Ready and other educational-technology, or “ed-tech,” platforms.

Of course, American education has had a rough few decades; student achievement continues to fall ever further behind other developed nations. Partisan tribalists may blame their favorite villains — lazy union teachers and woke-ness for the Right, structural racism and poverty for the Left. But both political parties have been equally guilty of legislating more and more standardized testing over the past 25 years, creating an ideal environment for Big Tech to hawk “data-based” panaceas like i-Ready.

Claude Blattman · AI for Researchers & Managers • Chris Blattman

In January 2026 I started building AI workflows with Claude Code. What seemed impossible then — inbox triage, meeting capture, proposal drafting, project dashboards, trip planning — is running today. “Claude Blattman” isn’t real, but the tools are. I’ve never coded in my life, so if I can do this you can.

…Like most academics, the work that matters — the research, the writing, the thinking — gets buried under an avalanche of email, coordination, proposals, and administrative overhead. I manage a large portfolio of research projects simultaneously, each with distributed teams across multiple countries. I spend more time answering emails and writing grant reports than doing the science I was trained for.

For the past year I intensively used AI chatbots. They were invaluable — deep research, better drafts, faster brainstorming, decent writing feedback. But they were limited. The time savings were real but modest.

The Graveyard of Destructive Ideas

How do destructive ideas and bouts of collective madness so quickly become policy, law, and the status quo? After all, most have little public support—and are not Western nations supposedly rationally governed?

There is usually a multi-step process on the road to these self-destructive fits of society-wide insanity.

The suicidal impulse so often begins with left-leaning researchers in elite universities (i.e., the tenured in search of a novel, grant-getting theory). They begin insisting that a new existential threat requires immediate government intervention, novel legislation, ample funding, and public awareness of the impending danger.

So out of nowhere, the public is warned that the scorching planet will be inundated by rising seas in a mere decade. Or that millions of transgender youth are our next civil rights frontier, given that they suffer in silence without political advocacy, new laws, programs, and the chance for “life-saving,” powerful hormonal treatments and radical sex-reassignment surgeries. Indeed, the travel time from an outlandish idea by the faculty lounge to liberal status quo is a mere few years.

Next, the media, hand-in-glove with academia, springs into action to persuade the skeptical public to “follow the science” and “trust the experts.” It castigates any doubters as cranks or “conspiracy theorists” who spread “disinformation” and “misinformation”; or as racists, nativists, sexists, homophobes, and transphobes who must be silenced.

Hollywood and sports celebrities often piggyback on the frenzy, hijacking awards ceremonies and pre-game national anthems to out-virtue-signal each other, warning the public that they must adapt and change—or else!

The Slow Death of the Power User

These were not professional circles. You didn’t need a CS degree. You needed curiosity and stubbornness and a tolerance for reading things that were too long and trying things that didn’t work on the first ten attempts. The culture valued that and passed it down. Kids learned by watching, by lurking in forums, by getting their stupid questions answered by people who then expected them to answer someone else’s stupid questions eventually. The knowledge propagated because the culture treated knowledge as worth propagating.

That culture didn’t die because the knowledge became irrelevant. It died because it became economically inconvenient. The platforms that replaced the open internet — YouTube, Reddit, Discord, eventually TikTok — are consumption platforms. Their business model requires passive engagement. A user who spends three hours going down a documentation rabbit hole, breaking things in a terminal, and actually understanding something is worth less to them than a user who watches three hours of content. They don’t ban technical material. They algorithmically deprioritize anything that demands active engagement, they reward passive consumption, and they shape the culture of their platform accordingly over years and years until the culture that emerges is one that treats passive consumption as the default relationship with technology

March 11 Madison School Board Candidate Forum

Two Madison School Board seats will be decided by voters on April 7, and the Cap Times will bring together the candidates for each seat in a public forum on Wednesday, March 11, at La Follette High School.

The moderators will be Cap Times education reporter Erin Gretzinger and Taylor Kilgore of the Simpson Street Free Press, which provides journalism and writing training for Dane County students in grades 3 through 12.

The candidates for the two seats are:

Seat 6: Blair Mosner Feltham and Daniella Molle

Seat 7: Dana Colussi-Lynde and Nicki Vander Meulen

The forum is free and will run 7-8 p.m. in Room 1353 at La Follette High, 702 Pflaum Road. To get to Room 1353, enter the high school through its Arts Entrance from the main parking lot, and look for signs and greeters to guide you to the room.

——-

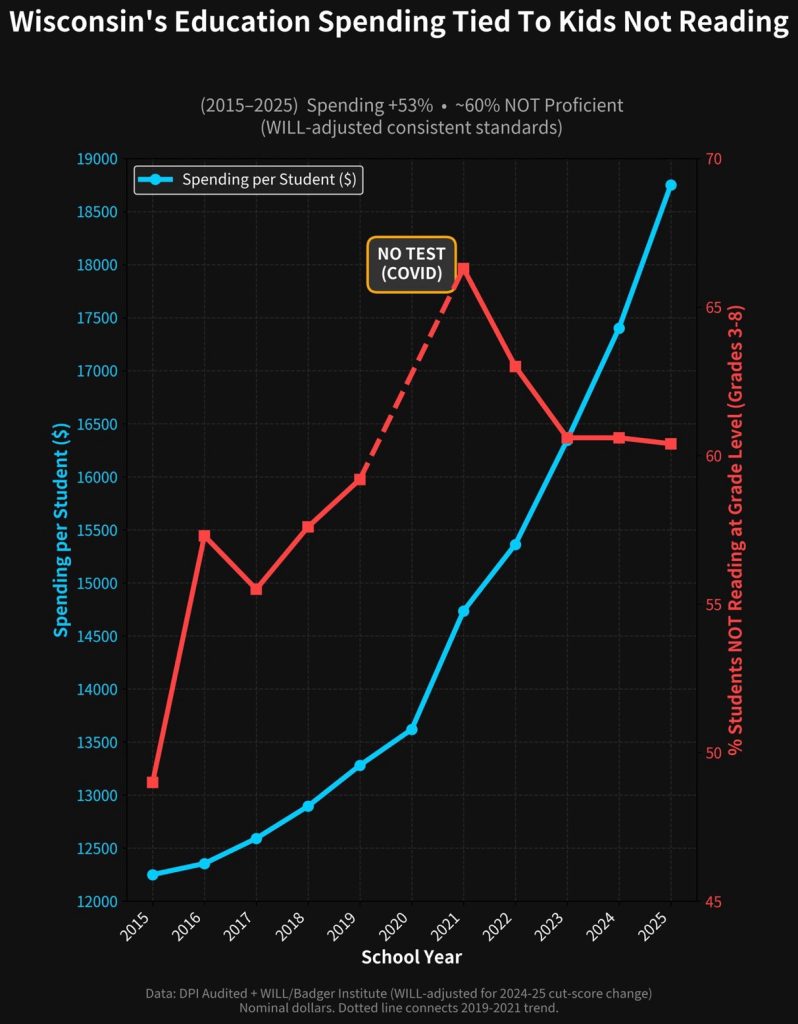

1998! Money and school performance.

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

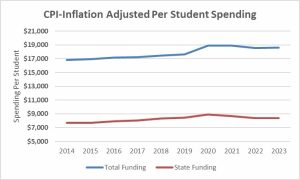

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

Madison School District acknowledges alleged dog food incident as parent seeks answers

The Madison School District has broadly confirmed an incident involving a student eating dog food at school but didn’t give any additional information beyond the fact that a teacher has been placed on leave while the claim is investigated.

The mother of the student who was involved held a press conference Friday at the state Capitol, backed by state Rep. Shelia Stubbs, D-Madison, the Autism Society of Wisconsin, the NAACP and other supporters, in which she detailed what she believed happened, although the Wisconsin State Journal has been unable to confirm the allegation.

According to the mother, Debra Hawkes, a teacher left an opened can of dog food in the same room as Hawkes’ autistic 15-year-old son, which was discovered by the next teacher assigned to her son. That teacher took a photo of the can and sent it to the principal, Hawkes said, who told her about the incident the following week.

“I should have got some answers by now. I should feel a little bit more comfort,” Hawkes said. “I do by the grace of God, but as far as Madison East High School, they didn’t give me nothing.”

Stubbs, who represents part of Madison’s east side in the state Legislature, said she was at “a complete loss of words” when she heard from Hawkes. The school district has given Hawkes the “bare minimum information,” Stubbs said.

“This is shameful, and this is unacceptable,” Hawkes said. “As a former special ed teacher, I’m appalled that this incident took place, and that families and students are suffering from mistreatment from staff and do not get the response that is necessary — and that is immediately.”

Civics: The Builder Class vs The Luxury Beliefs Class

Below the penthouse party, rubble, burned lots, and boarded storefronts stretch across neighborhoods where the cost of those cocktail-party convictions actually landed.

My father struggled with alcoholism. He put me and my brother through real trauma. As Asian Americans we just went into society assuming we were fine, and it came out in strange ways I didn’t have language for.

Then I sat down with Rob Henderson.

Henderson grew up in Los Angeles. Ten foster homes. Each of his three names, he told me, “were taken from adults that I no longer speak with and have essentially either neglected or abandoned me during my childhood.” Air Force at 17. Yale on the GI Bill. PhD from Cambridge. Along the way he spotted a pattern that explains why California keeps getting worse for the people politicians claim to help. He calls them luxury beliefs: ideas that cost nothing to hold if you’re rich and everything if you’re poor.

California is the world capital of luxury beliefs. And the body count is rising.

📚 Hillsdale College’s K-12 Curriculum School Program📚

Hillsdale College equips school founding groups and established brick-and-mortar public charter and private schools with the core curriculum and recommendations needed to build moral character, civic virtue, and rich knowledge in the liberal arts and sciences.

All Hillsdale College Curriculum School resources are provided at no cost to affiliated schools.

Curriculum schools receive:

📘 The K-12 Program Guide, a complete curriculum blueprint:

- 688-page comprehensive guide

- Covers K–12 in every core subject

- Full scope & sequence

- Vertically and horizontally aligned

- Vetted Books & Primary Sources

- Philosophical guidance on major subjects

Medicine & Marx

When President Xi Jinping addressed the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China last month, he spoke of “the scientific truth of Marxism-Leninism”.

Marxism (with Chinese characteristics), as President Xi went on to set out, is to be the foundation for a Healthy China. Who would dare today in the West to praise Karl Marx as the saviour of our wellbeing? Marx is long dead. He died physically on March 14, 1883. He died metaphysically in 1991, as the Soviet Union ebbed away into a newly independent Russian state. The Communist experiment had stuttered, faltered, and finally failed. It’s legacy? As Michel Kazatchkine wrote in The Lancet last month, the health system in the Soviet era “rapidly deteriorated” in its later years, leading to “inadequate availability of medical drugs and technologies, poorly maintained facilities, worsening quality of health care, and falling life expectancy”. But is it fair to consign Marx to the margins of the history of health? May 5, 2018, is the centenary of Marx’s birth. It is a moment to reappraise Marx’s contribution to medicine and to discover if his influence is quite as harmful as contemporary wisdom would suggest.

St. Paul Public Schools executive chief of schools to leave district

St. Paul Public Schools’ executive chief of schools Andrew Collins’ last day with the district is March 13, according to district officials.

A part of the district’s senior executive leadership team, Collins oversees the district’s athletics director and its five assistant superintendents. He has worked in the district in various roles, including as a principal.

A new position for a senior executive officer of school leadership and operations will replace Collins’ role is currently accepting applications, with an expected July 1 start date.

“It’s been a distinct pleasure and absolute privilege to serve the students, families and staff of Saint Paul Public Schools,” Collins said in a statement Wednesday. “I wish them all the best as they end this school year. I also want to express my deep appreciation for and gratitude to our community, staff and many community partners who have contributed to our collective successes over the years. As I consider new opportunities, I am committed to continuing to serve, invest in and build a stronger future for our youth and their families.”

‘An AlphaFold 4’ – scientists marvel at DeepMind drug spinoff’s exclusive new AI

“It’s a major advance, on the scale of an AlphaFold4,” referring to an unreleased future generation of Google DeepMind’s technology, says Mohammed AlQuraishi, a computational biologist at Columbia University in New York City who is working to develop fully open-source versions of AlphaFold. “The problem, of course, is that we know nothing of the details.”

The Wisconsin Higher-Ed Reform Model

Presently, plummeting college enrollment strengthens any such conservative bargaining. While enrollment at UW-Madison has largely held steady, enrollment has collapsed across the rest of the system, and forecasts predict a continued downward trend. Reality is unforgiving, and fewer students will force difficult cuts whether the Left likes it or not.

As Shelton concedes, “UW-Oshkosh cut about 20 percent of its entire workforce, UW-Platteville laid off over one hundred staff, the chancellor at UW-Parkside upheld the dismissals of several beloved lecturers because of budget cuts, and, on my campus, our chancellor sought to eliminate degree options for students.”

If salaries or hiring are on the line, falling enrollments could force other useful housekeeping. Do you, dear professor, want to lose your job, or should we redirect grant funds from the DEI office? I’m not a betting man, but I know where I’d toss my chips here.

The second path for higher-education reform is simple opposition. At the Conservative Education Reform Network (which I direct), we’re fond of emphasizing that conservatives are often better at explaining what we’re against than what we’re for. Through our network, we want to leverage the intelligent thinking of our members to propose and implement positive changes in our K-12 schools and institutions of higher education.

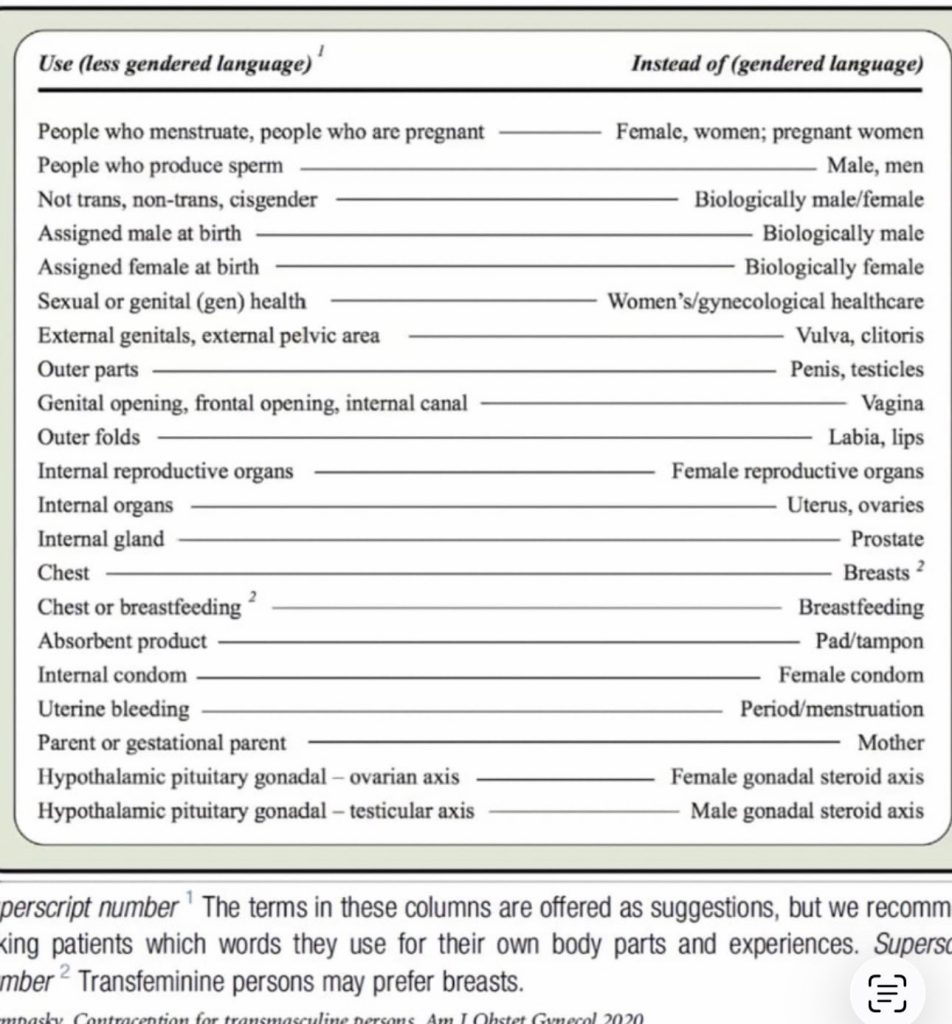

“Here is what @usask medical school students are learning in MEDC 409.8, Preparation for Residency”

Civics: Tech Companies Shouldn’t Be Bullied Into Doing Surveillance

Now, the U.S. government is threatening to terminate the government’s contract with the company if it doesn’t switch gears and voluntarily jump right across those lines.

Companies, especially technology companies, often fail to live up to their public statements and internal policies related to human rights and civil liberties for all sorts of reasons, including profit. Government pressure shouldn’t be one of those reasons.

Whatever the U.S. government does to threaten Anthropic, the AI company should know that their corporate customers, the public, and the engineers who make their products are expecting them not to cave. They, and all other technology companies, would do best to refuse to become yet another tool of surveillance.

Civics: In theory, the state Code of Judicial Conduct forbids judges and judicial candidates from engaging in most partisan conduct.

Chris Rickert:

“Given that, I think it’s safe to say that the Dane Dems does not traditionally endorse judicial candidates,” he said. “However, there is no rule that prohibits the party from endorsing in judicial races.”

Among the candidates the state Democratic Party has endorsed are the two most recent additions to the state Supreme Court, Janet Protasiewicz and Susan Crawford.

Grades now hyper-inflated at UW-Madison

Canadian universities have a remedy

Grade inflation continues unabated at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

The average GPA for undergraduate students at Wisconsin’s flagship university increased to 3.48 in the recently completed fall semester — up from 3.28 just 10 years ago and close to the 3.5 midpoint between an A and B average, according to reports available from the Office of the Registrar.

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers

|

(42 minutes); paraphrased:

30 years ago, Massachusetts adopted teacher content knowledge requirements (MTEL) and increased pay:

Massachusetts undertook sweeping education reforms in 1993 that linked funding increases to comprehensive reforms, ranging from curriculum and accountability changes to a new three-part teacher licensure test whose pass rate was initially just 41 percent.

Today, Massachussetts has the highest performing public schools in the country. Can we do that here?

Time flies. My 2019 question to Governor Evers (Former Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Superintendent).

2013: Alan Borsuk:

The Massachusetts test is about to become the Wisconsin test, a step that advocates see as important to increasing the quality of reading instruction statewide and, in the long term, raising the overall reading abilities of Wisconsin students. As for those who aren’t advocates (including some who are professors in schools of education), they are going along, sometimes with a more dubious attitude to what this will prove.

Legislation and Reading: The Wisconsin Experience 2004-.

Deeper dive: Wisconsin’s one attempt at implementing an elementary reading MTEL style content knowledge requirement: Foundations of Reading (FORT).

I also gave him a copy of Fast Lane Literacy – a big effort to accelerate learning to read.

Learn faster. Achieve escape velocity!

Madison leaders demand action on report that student was fed dog food

As authorities investigate allegations that an East High School staff member fed dog food to a student, state Rep. Shelia Stubbs and other community leaders called on the Madison school district to expedite its review and release more information.

At the state Capitol Friday alongside Stubbs and others, Debra Hawkes said the staff member fed her 15-year-old son, Jaden, a can of wet dog food Feb. 13. Hawkes said her son is autistic and non-verbal.

Hawkes learned about the incident the following week and went to the high school several times asking for more information before meeting with the principal, she said.

“I should have got some answers by now. I should feel a little bit more comfort,” Hawkes said. “I do by the grace of God, but as far as Madison East High School, they didn’t give me nothing.”

Stubbs, who represents part of Madison’s east side in the state Legislature, said she was at “a complete loss of words” when she heard from Hawkes. The school district has given Hawkes the “bare minimum information,” Stubbs said.

“This is shameful, and this is unacceptable,” Hawkes said. “As a former special ed teacher, I’m appalled that this incident took place, and that families and students are suffering from mistreatment from staff and do not get the response that is necessary — and that is immediately.”

——-

1998! Money and school performance.

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

k-12 Tax & $pending Climate: Chicago’s Pay Day Loans

Hmm, we wondered. Why such a difference?

As it turns out, the Johnson administration wants to keep the cash-strapped city from having to make payments on these bonds for another three years. The extra amount the city is borrowing would go largely toward making interest payments on the debt through 2029.

In describing the arrangement to us, Fitch actually used the dreaded municipal-bond financing term, “scoop and toss.” As in the frowned-upon practice of refinancing existing debt and extending it into the future, thereby raising the total cost of whatever costs that initial debt was covering in the first place — a method Chicago mayors largely have eschewed since Richard M. Daley retired.

——

The latest move is for Chicago to take on more debt, not pay it (not even interest) during Brandon Johnson’s reign. Yolo!

Large-scale online deanonymization with LLMs

We show that large language models can be used to perform at-scale deanonymization. With full Internet access, our agent can re-identify Hacker News users and Anthropic Interviewer participants at high precision, given pseudonymous online profiles and conversations alone, matching what would take hours for a dedicated human investigator. We then design attacks for the closed-world setting.

Given two databases of pseudonymous individuals, each containing unstructured text written by or about that individual, we implement a scalable attack pipeline that uses LLMs to: (1) extract identity-relevant features, (2) search for candidate matches via semantic embeddings, and (3) reason over top candidates to verify matches and reduce false positives. Compared to prior deanonymization work (e.g., on the Netflix prize) that required structured data or manual feature engineering, our approach works directly on raw user content across arbitrary platforms.

More: And right on schedule: there goes pseudonymity on the Internet.

Houston will close 12 schools in unanimous board vote

Nusaiba Mizan, Megan Menchaca:

“There’s over 40 schools facility-wise that could possibly be closed,” Miles said. “If we did it just by the numbers, just by the data, but we’re not doing that.”

Parents and community members said they felt blindsided by the sudden announcement — a frustration many repeated during the meeting Thursday.

——-

more.

The Dyslexia Myth

Parents are often relieved when their child who has trouble reading is finally diagnosed with dyslexia. At last, the problem has a name and expert diagnosis to go along with it. A dyslexic child can receive specialized instruction and gain extra access to staff support and resources. And the diagnosis offers an instant response to those who assume the child is stupid or lazy.

For these parents, their child’s dyslexia diagnosis is similar to a diagnosis of a bad knee. You visit your doctor to have your troublesome limb checked out, wondering whether the cause of your discomfort is an infection, a ligament injury, arthritis, or possibly a tumor of some kind. The doctor runs a series of tests, diagnoses the problem, and then recommends a course of treatment that has been found by detailed research to be effective.

But things aren’t quite so simple. The reality is that, as helpful as some parents may find it, the present system of dyslexia diagnosis is scientifically flawed, wasteful of resources, and inequitable in its social effects. The prohibitive cost of testing and other barriers means that most struggling children will never gain access to the relevant resources. In order to reform the current system, we must first dispel the myth that underpins it.

“The present system of dyslexia diagnosis is scientifically flawed.”

“When it comes to dyslexia diagnosis, this expectation is misplaced.”

Dyslexia is sometimes understood as synonymous with reading disability—a severe difficulty with reading and spelling that persists despite appropriate instruction—and sometimes as a condition only experienced by some struggling readers, identified on the basis of cognitive tests. Parents tend to prefer the latter definition, which is why they sometimes pay thousands of dollars for a detailed psychological assessment involving multiple tests.

Massachusetts needs to catch up with Mississippi on reading instruction

A 2023 study of 19 teacher preparation programs in Massachusetts underscored the need for this requirement. That study, conducted by the National Council on Teacher Quality, gave grades of D or F to 15 of those 19 programs for their literacy training, while only 3 received an A or better. Several of the state’s largest teacher preparation programs, including at Boston University, Lesley University, and UMass Boston, were among the programs receiving failing or close-to-failing grades. (A number of teacher preparation programs refused to provide data to the council. And for a new report due in June, UMass Amherst claimed that its reading curricula was proprietary information, a view that was sharply questioned by the Commonwealth’s supervisor of public records, documents show.)

———

more.

———

1998! Money and school performance.

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

For College Applicants, Pressure to Make Summers Count Has Gotten Even Worse

The country’s most ambitious high-schoolers now have one more thing to fret over: crafting their “summer story.”

Overachieving teenagers have long pursued a smorgasbord of résumé-polishing summer activities. But a range of impressive summer pursuits is no longer enough, some college advisers say. Students now feel pressure to specialize—as early as their freshman summer—in interests they want to pursue in college.

The idea, college advisers say, is to assemble a list of summer pursuits that show increasing mastery in a distinct specialty. That “narrative” can help students stand out in a sea of all-rounders, they say.

So many students now have high GPAs and strong test scores that the competition has extended to the summer, said Lisa Bain Carlton, a college counselor in Austin, Texas.

“A significant differentiator is: What have you done outside the classroom? And what does it tell us about what you’re going to do at our college?” Bain Carlton said. Summer activities have always played a role in college admissions, but now “it’s like a train that’s taken off and gotten faster and faster and faster,” she said.

The decline of confidence in higher ed

FIRE data shows one-third of Americans have no confidence in U.S. colleges and universities

Americans’ confidence in U.S. colleges and universities remains near historic lows. Although some have suggested that public opinion about higher education may be stabilizing or rising, our latest survey finds little evidence of meaningful recovery.Subscribe

In our latest poll, conducted in partnership with NORC at the University of Chicago, less than a third of Americans say they have “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in U.S. colleges and universities. That’s statistically indistinguishable from 2024 and 2025 levels. At the same time, almost the same proportion report having “very little” or no confidence at all.

These results stand in stark contrast to public opinion a decade ago. In 2015, 57% of Americans told Gallup they had a great deal, or quite a lot, of confidence in higher education, while just 10% expressed very little confidence. By 2018, these figures were starting to slip, with high confidence decreasing and low confidence increasing. Since then, the decline has accelerated. Compared to 2015, the share of Americans expressing high confidence has fallen by 26 percentage points, while the share expressing very little confidence has nearly tripled.

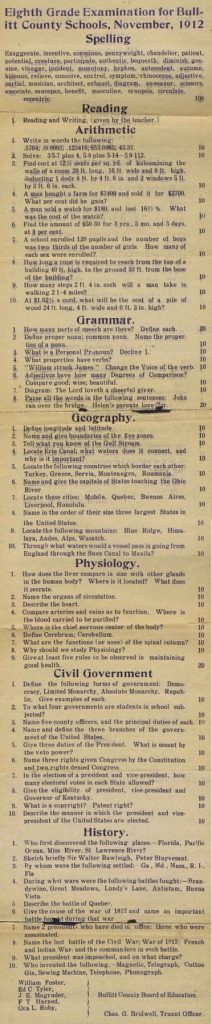

k-12 Rigor: 1912 edition

In 1912, eighth graders in rural Kentucky were asked to define democracy, a republic, and an absolute monarchy, and provide examples of each.

Today, only 35% of high school seniors are proficient in reading.

You can read these words. That does not mean you are literate.

UCLA continues its “diversity” mania while damaging its reputation.

The DEI practices at America’s colleges and universities have been justly criticized for being anti-meritorious, unconstitutional, racist, and costly. However, a recent lawsuit against UCLA’s medical school suggests that its discriminatory admissions policies could potentially have negative public-health consequences, as well.

That’s quite an indictment against what has long been regarded as a premier medical school.

The Department of Justice argues that UCLA uses a “systemically racist” approach to med-school admissions.Last May, the groups Do No Harm and Students for Fair Admissions, as well as an unsuccessful white applicant, sued UCLA’s medical school, arguing that “various UCLA officials [had engaged] in intentional discrimination on the basis of race and ethnicity in the admissions process.” They have now been joined by the U.S. Department of Justice, which argues that the school uses a “systemically racist” approach in admissions, favoring Hispanic and black applicants over white and Asian ones. The government’s brief declares this to be a matter of public importance and seeks relief for future applicants who shouldn’t be forced to compete in a race-based system that may prejudice them.

The plaintiffs insist that UCLA must base admissions on individual ability and not on membership in some favored group.

The Edge of Mathematics

Terence Tao, the legendary mathematician, explains the promise of generative AI.

Wong: What improvements are you hoping or expecting to see from generative-AI models in the next year or two?

Tao: There’s a middle ground where we want to encourage responsible AI use and discourage irresponsible AI use. It is a delicate line to tread. But we’ve done it before. Mathematicians routinely use computers to do numerical work, and there was a lot of backlash initially when computer-assisted proofs first came out, because how can you trust computer code? But we’ve figured that out over 20 or 30 years. Unfortunately, the timelines are much more compressed now. So we have to figure out our standards within a few years. And our community does not move that fast, normally.

One very basic thing that would help the math community: When an AI gives you an answer to a question, usually it does not give you any good indication of how confident it is in this answer, or it will always say, I’m completely certain that this is true. Humans do this. Whether they are confident in something or whether they are not is very important information, and it’s okay to tentatively propose something which you’re not sure about, but it’s important to flag that you’re uncertain about it. But AI tools do not rate their own confidence accurately. And this lowers their usefulness. We would appreciate more honest AIs.

Civics: Amazon BUSTED for Widespread Scheme to Inflate Prices Across the Economy

The scale of the scheme is almost unfathomable; according to its latest investor reports, Amazon earned $426 billion of revenue in its 2025 North America online shopping business, which is about $3000 for every household in America. As Stacy Mitchell noted, prices for third party goods on the online platform, roughly 60% of its total sales, have been going up at 7% a year, more than twice the rate of inflation. And because this scheme impacts goods sold off of Amazon’s website as well, there’s a reasonable chance that it has had an impact on price levels overall in America. With a similar Pepsi-Walmart alleged conspiracy revealed earlier this year, it’s becoming increasingly clear that consolidation and price-fixing are linked to inflation.

How exactly does the scheme work? Long-standing readers of BIG may remember a piece in 2021 titled “Amazon Prime is an Economy-Distorting Lie” in which I laid out what’s happening. At the time, the D.C. Attorney General, a lawyer named Karl Racine, sued Amazon for prohibiting vendors that sold on its website from offering discounts outside of Amazon. Such anti-discounting provisions raise prices for consumers, and prevent new platforms from emerging to challenge Amazon.

The key leverage point for Amazon is the scale of its Prime program, which has 200 million members nationwide. As Scott Galloway noted a few years ago, more U.S. households belong to Prime than decorate a Christmas tree or go to church.

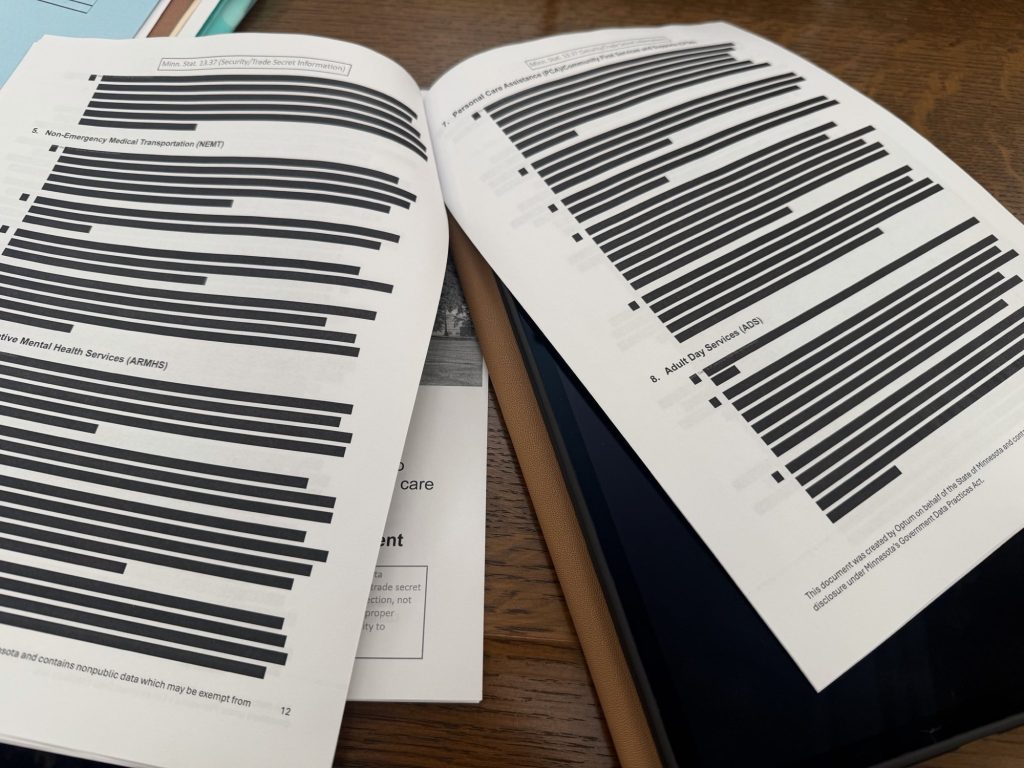

“Ghost Students” & Fraud

Who were Joe Haker’s students? They were what’s become known as “ghost students”: fraudsters, typically international, that apply for colleges under false or stolen identities while never intending to attend or gain a degree. The digital applications are often made easier by AI. The fraudsters portray themselves as in need of significant financial aid, wait for that aid to be disbursed, and then pocket the extra funds. They can also steal and sell student technology resources.

Fraudsters usually target fully online programs and community colleges, as it is easier for false students to slip by undetected. Mark Grant, with the Minnesota State College Faculty, said yesterday that some poor-quality work submitted by foreign ghost students is unfortunately indistinguishable with the legitimate work of some struggling students, making fraud discernment difficult for professors.

The enrollment fraud working group presented a recommendations report yesterday to the committee. Craig Munson, chief information security officer for Minnesota State, testified that the working group had created an Enrollment Fraud User Guide for Minnesota’s state colleges and universities. The User Guide, focused on cybersecurity and technical recommendations, was designed to be used by all 33 Minnesota state colleges and universities.

The working group recommended that the legislative committee expand the collaboration between higher education and the legislature by formalizing the fraud group as a standing committee and mandating a yearly fraud report to the legislature. They also recommended that fraud awareness training be provided to students and faculty members, that institutions be required to adopt the suggestions made in the Enrollment Fraud User Guide, that continued attempts at collaboration be made between the state and federal government, and that equity impact assessments take place before implementing any safeguards.

K-12 Tax & $pending Climate: Rax base, Block & “ai”

But had he not leaned into the AI transition, he might have had to lay off more people, slowly, and over time, as faster competitors went after his market share.

Epstein & University Influence

Joshua Chaffin, Neil Mehta & Douglas Belkin:

Just this week, Richard Axel, a Nobel laureate Columbia professor, and Lawrence Summers, the decorated economist and former Harvard president, stepped down from positions at their institutions because of their Epstein ties.

Axel said Tuesday that he would resign as co-director of Columbia’s Mind Brain Behavior Institute, calling his association with Epstein “a serious error in judgment.” Summers, meanwhile, said Wednesday that he would end his tenure as a Harvard professor at the end of the academic year. In November, he took leave from teaching duties, apologized and said he was “deeply ashamed” after the release of a batch of emails in which he asked Epstein for advice on “getting horizontal” with a woman he was pursuing.

Last week, Bard College retained a law firm to review President Leon Botstein’s ties to Epstein after the latest emails released by the Justice Department showed what appeared to be a warm personal relationship—even years after Epstein pleaded guilty in 2008 to charges of solicitation of prostitution and procurement of minors to engage in prostitution.

In a statement earlier this month, Botstein said Epstein wasn’t a friend and that his dealings with him were “only for the sole purpose of soliciting donations for the College.”

accounting and k-12 budget practices

Minneapolis Public Schools (MPS) has announced changes to its Revenue Recognition practices; the move follows the dismissals of 3 senior finance ppl (incl CFO & Controller) in Dec & an increase to the deficit projection for next SY. Many indicator lights blinking red, but I want to unpack the RR piece. 1/

Low Tax States Gaining Babies in the Post-COVID Shuffle

In March 2020, life shut down, and many couples found themselves with a little extra time on their hands. Some of them welcomed a new member of the family nine months later, and those COVID babies are now getting old enough for kindergarten—and the geography of American family life has been indelibly changed in the meantime.

Highlights

- Compared to their 2019 population levels, the 20 states that voted for former vice-President Kamala Harris in 2024 saw a decline in people in their 20s and kids under 10. Post This

- States with cheaper housing tend to have better luck attracting or keeping parents of young kids. The majority of these states are politically red. Post This

- For states that want to remain attractive to families, it’s vital to focus on the fundamentals of good governance—affordable housing, solid job growth, and the political center rather than either extreme. Post This

As the Institute for Family Studies has highlighted, red states have higher birth rates than blue states. Red states also have seen higher rates of in-migration from other states than blue states in the years following the pandemic. There is clearly an increasing correlation between a state’s partisan valence and rates of family formation. We are seeing a kind of “big sort” of American families, which can help us predict where children will and won’t be seen and heard through the next decade.

First, Honesty. Then, Multiplication Tables.

In many ways, what happened with math instruction in the United States mirrors better-known problems with how our children have been taught to read.

As outlined in the deeply reported Sold a Story podcast, American reading instruction shifted from teaching phonics and reading fundamentals through rote practice to a more “vibes-based” approach centered on sight words and “balanced literacy” delivered in cozy classroom book corners. We chose to believe that exposing kids to good books would be enough to teach them to read and to love reading. It didn’t work.

Our trouble with math education is similar. This story hasn’t been as deeply reported yet, but it follows the same cultural trajectory. It even has a similar antihero, Jo Boaler, a professor of education at Stanford University, is seen by some in education as a ”beacon of hope.” But her critics allege that she “made bold assertions with scant evidence” which they feared would “water down math and actually undermine her goal of a more equitable education system.”

Boaler wrote a book called Math-ish that aims to help students find “joy, understanding and diversity in mathematics.” Influential in developing the pedagogical shifts that informed Common Core standards—and even in how teachers are trained to teach mathin states, like Texas, that haven’t adopted Common Core—Boaler aimed to help students experience math instruction more “broadly, inclusively, and with a greater sense of wonder and play.”

That certainly sounds more delightful than a worksheet—even akin to the reading corners with twinkle lights and beanbag chairs. But seasoned math teachers told me they see it as a dereliction of duty. (The local educators I interviewed weren’t allowed to speak on record per school district policy.)

———

2014: 21% of University of Wisconsin System Freshman Require Remedial Math

How One Woman Rewrote Math in Corvallis

Singapore Math

Discovery Math

Math Forum 2007

k-12 tax & $pending climate: Chicago credit rating downgraded by Fitch, KBRA

Chicago’s credit rating was downgraded by two agencies today, a rebuke that lands squarely in the middle of an ongoing budget fight between Mayor Brandon Johnson and the City Council.

The downgrade reflects mounting concern about the city’s reliance on borrowing and one-time revenue — and serves as a “wake-up call,” said one municipal finance expert, that political infighting is compounding Chicago’s long-standing structural deficit.

Despite the warning, Johnson and the City Council coalition that passed a budget over his objections sought to shift the blame to the other, a clear sign the 2027 budget process will be just as combustible as last year.

While the Council increased the city’s advance pension payment to shore up its four beleaguered retirement systems, it also kept $449 million in borrowing for operating costs that had been included in Johnson’s proposal.

The agency also downgraded the city’s outstanding bonds, from AAA to AA+, tied to the Sales Tax Securitization Corporation, a vehicle created by former Mayor Rahm Emanuel to separate the city’s sales tax revenue from the general fund in order to borrow at lower rates. The city has increasingly relied on the STSC for new bond issuances.

KBRA, another credit rating agency, also downgraded the city’s general obligation bonds and assigned a BBB+ rating, just above non-investment grade status, to the upcoming sales.

———

more.

civics: Epstein & the justice system

New documents — made public for the first time — show in greater detail how Epstein tried, and often succeeded, in influencing almost every level of the criminal justice system that threatened to disrupt his sex trafficking and money laundering empire.

Epstein’s efforts to corrupt the justice system is important because, had some of these figures rigorously investigated and monitored Epstein, he may not have been able to continue to sexually abuse women and girls for another decade.

This story is based on a Miami Herald review of thousands of documents released by the Justice Department, court records and interviews with key people involved in the Epstein case.

The documents — released in response to the Epstein Files Transparency Act passed by Congress last year — reveal how Epstein wooed state and federal prosecutors, assistant district attorneys, sheriff’s deputies, probation officers, federal marshals and customs and border patrol officers.

Why Universities Keep Losing the Argument

In addition to its tension with underlying constitutional principle, this is almost certainly a counterproductive response to populist challenges. Bollinger’s response to collapsing trust is to insist that citizens and their direct or indirect representatives are entitled to only a nominal role in the direction of institutions that claim to act in their interest and spend money derived from taxes they pay. Rather than defusing the issue, he vindicates suspicion that academics believe they are philosopher kings.

Bollinger is also wrong to suggest that the status of a “branch” of government confers independence from the other branches. At one point he suggests that university presidents called before congressional committees should conduct themselves in a manner comparable to Supreme Court justices, who generally refuse to comment on their rulings in particular cases. Bollinger does not mention that Supreme Court justices are nominated by elected presidents, confirmed by elected senators, and subject to removal if their conduct is found outrageous. Judges are permitted a high level of discretion because they have been chosen and assessed by members of other branches, and because their personal conduct and institutional budgets are subject to external judgment. Bollinger is presumably not encouraging similar constraints on faculty members and administrators, which would go beyond even the oversight exercised by state governments over public universities.

What Bollinger really seems to have in mind for the academy is not a component of republican government at all. His discussion of “the university’s role as the fifth branch of the nation” evokes the medieval idea that the political community is divided into distinct “estates” that cooperate for certain purposes but are primarily accountable to their own members. Given the medieval origins of the university, it’s not surprising that there’s an affinity between the concepts. Still, a conception of the academy as an autonomous estate or guild is hard to square with a Constitution authorized by an undivided “we, the people.”

Civics: “Record increase in last four years driven primarily by illegal immigration”

Steven A. Camarota and Karen Zeigler:

The government’s January 2025 Current Population Survey (CPS) shows the foreign-born or immigrant population (legal and illegal together) hit 53.3 million and 15.8 percent of the total U.S. population in January 2025 — both new record highs. The January CPS is the first government survey to be adjusted to better reflect the recent surge in illegal immigrants. Unlike border statistics, the CPS measures the number of immigrants in the country, which is what actually determines their impact on society. Without adjusting for those missed by the survey, we estimate illegal immigrants accounted for 5.4 million or two-thirds of the 8.3 million growth in the foreign-born population since President Biden took office in January 2021. America has entered uncharted territory on immigration, with significant implications for taxpayers, the labor market, and our ability to assimilate so many people.

Highlights from the January 2025 data include:

- At 15.8 percent of the total U.S. population, the foreign-born share is higher now than at the prior peaks reached in 1890 and 1910. No U.S. government survey or census has ever shown such a large foreign-born population.

——-

Meanwhile, foreign-born employment has been written UP by about 800,000 since Nov 2024 and now stands only about 100,000 less than on Liberation Day (rather than 670,000 loss).

K-12 Tax & $pending Climate: Wisconsin ranked among states with the highest property taxes

Wisconsin homeowners face one of the heaviest property tax burdens in the country, according to a new report from WalletHub.

The personal finance website compared property tax rates in all 50 states and the District of Columbia by using U.S. Census Bureau data, which it said shows the average U.S. household pays $3,119 a year in property taxes on their home.

“Some states charge no property taxes at all, while others charge an arm and a leg,” said Chip Lupo, a WalletHub analyst. “Americans who are considering moving and want to maximize the amount of money they take home should take into account property tax rates, in addition to other financial factors like the overall cost of living, when deciding on a city.”More: Journal Sentinel, experts answer data center questions at town hall

In Wisconsin, lawmakers have been trying to make a deal to lower surging property taxes. Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, a Republican, said Feb. 20 that it’s “very likely” lawmakers will return to pass a tax relief package in special session.

Gov. Tony Evers, a Democrat, said during his Feb. 17 State of the State addressthat he wouldn’t accept an earlier proposal from Republicans because it didn’t include a key demand: routing hundreds of millions in funding for a revenue stream for schools known as general school aids, which would also lower property tax rates.

——-

1998! Money and school performance.

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

Civics: FBI obtained Kash Patel and Susie Wiles phone records during Biden administration

The FBI subpoenaed records of phone calls made by Kash Patel and Susie Wiles, now the FBI director and White House Chief of Staff, when they were both private citizens in 2022 and 2023 during the federal probe of Donald Trump, Patel told Reuters on Wednesday.

Reuters is the first to report on the FBI’s actions that took place during the Biden administration, largely when Special Counsel Jack Smith was investigating whether Trump had interfered with the 2020 election and had hidden classified documents at Mar-a-Lago, according to Patel. Smith was appointed to take over that probe in November 2022.

New Yorkers Don’t Know How Much They Spend on Education

New York State leads the nation in education spending—more than $33,000 per-pupil, 91 percent above the national K-12 average. Yet according to a recent survey, most parents don’t know how much the state is shelling out.

50CAN, an education-advocacy group, recently released the second edition of its report on the “State of Educational Opportunity in America.” The report contains the results of the group’s survey of 23,000 parents across 50 states.

One question, which did not make the final report, asked parents to estimate how much is spent on each student in their state. New York’s results were shocking: Forty percent of the 415 respondents were “not sure,” while 29 percent guessed “less than $5,000.” Only 1 percent guessed the range (“$35,000 to under $40,000”) that accurately characterized last year’s per-pupil average ($36,293).

Why such a drastic underestimate? One possible explanation is the combination of declining student enrollment and a lack of clear academic improvements. Schools keep shrinking, and student performance hasn’t budged—so how could the state be leading the country in education spending?

“This disconnect between what’s spent and what people think is spent is longstanding in [New York]. The teachers’ unions and others have a self-interest in that narrative, so they can always ask for more and always blame the results on ‘scarce resources,’” Derrell Bradford, president of 50CAN, told me. “The truth is, after the pandemic, there are fewer students and more money in the system than there has ever been. It’s a shame kids aren’t getting the benefits while parents are kept in the dark about it.”

New York State has led the nation in per-pupil spending for 19 consecutive years. And no other large urban district spends nearly as much per student as New York City. In fiscal year 2022, for example, Gotham spent$38,163 per pupil, compared with $23,314 in second-place Los Angeles.

——-

30 October 2025 Madison School Board approves a $668,000,000 budget for 25,557 “full time equivalent” students.

Civics: Politics and the CDC

BREAKING: I’m suing the Trump Administration to challenge their illegal overhaul of the @CDCgov’s long-standing recommendations for children’s vaccinations.

compare the new CDC recommendations to Denmark’s recommendations for childhood vaccinations. are they not very similar now?

Deepseek & Claude

Deepseek got called out for scraping 150k Claude messages. So I’m releasing 155k of my personal Claude Code messages with Opus 4.5.

I’m also open sourcing tooling to help you fetch your data, redact sensitive info & make it discoverable on HF – link below to liberate your data!

How far back in time can you understand English?

A man takes a train from London to the coast. He’s visiting a town called Wulfleet. It’s small and old, the kind of place with a pub that’s been pouring pints since the Battle of Bosworth Field. He’s going to write about it for his blog. He’s excited.

He arrives, he checks in. He walks to the cute B&B he’d picked out online. And he writes it all up like any good travel blogger would: in that breezy LiveJournal style from 25 years ago, perhaps, in his case, trying a little too hard.

But as his post goes on, his language gets older. A hundred years older with each jump. The spelling changes. The grammar changes. Words you know are replaced by unfamiliar words, and his attitude gets older too, as the blogger’s voice is replaced by that of a Georgian diarist, an Elizabethan pamphleteer, a medieval chronicler.

Taxpayers aren’t paying, so there have been few chances for residents to say whether they wanted the controversial surveillance network in the first place.

Oona Milliken & Isabella Aldrete

The Las Vegas Metropolitan Police Department (LVMPD) quietly entered an agreement in 2023 with Flock Security, an automated license plate reader company that uses cameras to collect vehicle information and cross-reference it with police databases.

But unlike many of the other police departments around the country that use the cameras in their police work, Metro funds the project with donor money funneled into a private foundation. It’s an arrangement that allows Metro to avoid soliciting public comment on the surveillance technology, which critics worry could be co-opted to track undocumented immigrants, political dissidents and abortion seekers, among others.

“It’s a short circuit of the democratic process,” Jay Stanley, a Washington D.C.-based lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) who works on how technology can infringe on individual privacy and civil liberties, said in an interview with The Nevada Independent.

CIA World Factbook: 1990 – 2025

36 years of geopolitical intelligence preserved and structured for analysis. Every country, every field, every edition — parsed from the original CIA publications into a searchable, queryable archive.

The Los Angeles Unified School District is borrowing $250 million to settle sexual misconduct claims.

If you are wondering if this is in addition to the $500 million that the Los Angeles Unified School District borrowed less than a year ago to settle sexual misconduct claims, the answer is yes, the $250 million is in addition to the $500 million.

Experts say this will end up costing taxpayers more than $1 billion.

——-

200 Wisconsin teacher sexual misconduct, grooming cases shielded from public.

More.

“we’re just disguising mediocrity”

“Lowering standards, eliminating standardized tests, inflating grades… We’re not building better students, we’re just disguising mediocrity. Real education demands honesty.”

More than 8% of incoming students at UC San Diego need remedial math classes — despite having passed calculus or statistics in high school. That should worry us a lot.

more.

Mellon’s Deleterious Effect on the Humanities

To the Editor:

I am grateful to Michael S. Roth for taking the time to read my work, and for sharing his views on what I’ve written. I have admired much of his recent writing on higher education, particularly his eloquent criticism of the threats posed to academic freedom by the Trump administration. He is right that the government’s efforts to influence American universities in a more favorable ideological direction by withholding federal dollars is a form of soft “extortion.” I am surprised, then, that he is not troubled by the Mellon Foundation’s efforts to exert political pressure on American colleges and universities by offering badly needed humanities grants in exchange for ideological conformity.

I am surprised, too, that Roth is more distressed by what he takes to be my mocking tone than he is by what is detailed in my reporting: that scholars, desperate for funding, have had to politically contort their work in a bid to keep their research afloat, and that the many grant administrators I spoke with, some of whom have worked with Mellon for decades, described near uniform concern about Alexander’s leadership and its deleterious effect on the humanities and their own institutions.

As for the comparison Roth draws between myself, a left-leaning black writer whom he disagrees with on matters of educational policy, and the late Republican Senator Jesse Helms, a notorious anti-black segregationist, I’ll simply note: The Mellon Foundation provided Wesleyan $1 million for “interdisciplinary leadership training” in “antiracism practices” in 2020. I do not believe in these sorts of initiatives myself, but since Roth does, perhaps if any of that money is left over, he can use it on a racial sensitivity consultant.

——-

more.

“ideas for how to find your dream job and avoid a career you’ll regret”

For lots of young people, career paths feel like conveyor belts—the next test, the next application, the next college—without a pause to ask what they really want to do with their lives. After Gurley went to college, he landed a job at a famous tech company. A dream job, right? But he was bored, so he took a chance and leapt into the unknown, eventually finding his place in the world of venture capital.

Hard Parenting, Better Relationships: New Evidence

We recently surveyed 24,000 parents around the United States. One question we asked is on a lot of parents’ minds: how difficult is parenting? Many parents feel stressed or burdened by raising kids and would like to make it easier: 7.4% of parents in our survey say parenting is “very hard,” and 36.5% say it is “fairly hard.” We wondered if our data could point to ways in which parents could lighten their own load—both because we think parents could use a break, and because parents who describe parenting as easier are likelier to say they will have more children. Controlling for the number of kids, 48% of those who say parenting is very easy intend more children, vs. 38% of those who say parenting is fairly easy, 35% of those who say parenting is fairly hard, and 33% of those who say parenting is very hard. When parenting is too hard, fewer children are born.

Highlights

- Parenting feels easier when parents feel their partners and the surrounding community are more supportive, per new IFS survey. Post This

- Parental-enforced rules are associated with better relationships with kids, both in the parent’s own assessment and in the assessments of the teens we surveyed. Post This

- For dads, parenting feels hardest when kids are under 2, and easiest when kids are 9 to 11. For moms, parenting tends to feel easiest when kids are under 2, and hardest when kids are 4 to 7. Post This

“She’s also a member of the Madison School Board”

And here’s what Pearson is alleged to have done according to a criminal complaint as part of formal charges brought against her last week. She and a friend, Brandi Grayson, were out together just before Christmas. At about 11 PM they parked in a loading zone behind a theatre. When a security guard asked them to move they refused and verbally abused the guard. Grayson, who was driving, moved the car toward the guard in a way that he felt was threatening.

The theatre manager came out and again asked them to move the vehicle. They refused and in fact drove over some cones placed to mark off the no parking area. At one point Grayson called the manager a “Karen” and a “fat, white (expletive).”

It’s important to pause here and point out that back in 2020 during the incident Skidmore was apparently falsely accused of, Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway issued a statement saying in part, “No words of gender-based violence should ever be uttered by anyone, period, No profanity should be used towards members of the body and no such language, verbally or otherwise, should be used against anyone in our community.” And yet, the Mayor has had nothing to say about the incident involving Grayson.

———

1998! Money and school performance.

A.B.T.: “Ain’t been taught.”

8,897 (!) Madison 4k to 3rd grade students scored lower than 75% of the students in the national comparison group during the 2024-2025 school year.

Madison taxpayers have long supported far above average (now > $26,000 per student) K-12 tax & spending practices. This, despite long term, disastrous reading results.

Madison Schools: More $, No Accountability

The taxpayer funded Madison School District long used Reading Recovery…

The data clearly indicate that being able to read is not a requirement for graduation at (Madison) East, especially if you are black or Hispanic”

My Question to Wisconsin Governor Tony Evers on Teacher Mulligans and our Disastrous Reading Results

2017: West High Reading Interventionist Teacher’s Remarks to the School Board on Madison’s Disastrous Reading Results

Madison’s taxpayer supported K-12 school district, despite spending far more than most, has long tolerated disastrous reading results.

“An emphasis on adult employment”

Wisconsin Public Policy Forum Madison School District Report[PDF]

WEAC: $1.57 million for Four Wisconsin Senators

Friday Afternoon Veto: Governor Evers Rejects AB446/SB454; an effort to address our long term, disastrous reading results

Booked, but can’t read (Madison): functional literacy, National citizenship and the new face of Dred Scott in the age of mass incarceration.

When A Stands for Average: Students at the UW-Madison School of Education Receive Sky-High Grades. How Smart is That?

Legislative Letter to Jill Underly on Wisconsin Literacy

EdTech Commentary

In the $94 billion North American ed-tech market of 2026, Curriculum Associates stands as a dominant pillar. Founded in 1969, the firm operated for decades as a sleepy, also-ran textbook publisher before pivoting to the nascent e-learning market in the late aughts. Today, the company is a private-equity-backed juggernaut with more than 2,700 employees and $750 million in annual revenue — derived overwhelmingly from America’s taxpayer-funded public schools.

Curriculum Associates’ flagship product is i-Ready. First launched in 2011, it has evolved into two tightly intertwined screen-based products. i-Ready Inform is the diagnostic half: standardized “adaptive” tests given three times per subject annually. The other half is i-Ready Learning, which translates each student’s i-Ready Inform scores into algorithmically generated lessons called “My Path.” This takes the form of gamified multiple-choice math and English questions delivered by infantile cartoon characters with names like “Yoop Yooply” and “Snargg.”

“Gamified multiple-choice math and English questions [are] delivered by infantile cartoon characters with names like Yoop Yooply and Snargg.”

Civics: A pair of powerful groups on the Left are entering Wisconsin’s race for the Supreme Court. Planned Parenthood and End Citizens United on Monday both endorsed Taylor on Monday.

Taylor worked for Planned Parenthood as a lawyer before she became a judge.

“[Taylor] played a central role in advancing reproductive health and rights by shaping landmark legal and policy strategies to protect and expand access to contraception and family planning. She built and defended Wisconsin Medicaid’s family planning program, developed successful court and legislative strategies to secure contraceptive equity and prevent prescription denials, and helped elect pro-Planned Parenthood leaders statewide,” Planned Parenthood said in a statement.

Planned Parenthood added that they have a vested interest in Taylor’s election.

FBI raids LAUSD Supt. Alberto Carvalho’s home and office

Brittny Mejia, Richard Winton and Ruben Vives:

Federal authorities raided the home and office of Los Angeles Unified School District Supt. Alberto Carvalho on Wednesday morning, the FBI confirmed.

Law enforcement sources, who requested anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly, told The Times that the federal investigation specifically involves Carvalho. However, the precise motivation for the searches at his San Pedro home and LAUSD headquarters was not immediately clear.

FBI agents also searched a residence in Southwest Ranches, a town in Broward County, Fla., in connection with the investigation and have since cleared the scene, according to an FBI spokesman in Miami. Sources told The Times that the property is associated with Carvalho.

The FBI declined to share more information, citing the fact that the affidavits have been sealed by the court. Sources familiar with the probe said that the focus was Carvalho as opposed to the LAUSD, and that it would fall under the broad category of financial issues.

These Schools Want Civil Discourse on Campus. Even That Is Up for Dispute.

On the evening of Jan. 15, 26 undergrads gathered for dinner in a common room at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill to debate the fairness of college admissions post-affirmative action. The ground rules were clear: Nothing they said would leave the room. Nobody would be shouted down. No one would get ratted out on social media as “problematic.”

The students went at it with gusto. First-years from Hungary and Turkey lamented the systems in their home countries, where admissions are based purely on standardized tests rather than their interests or extracurriculars. A Black student from in-state criticized admissions based on test scores and GPAs for different reasons; given sharp disparities in secondary schools and family resources, some kids were already at a disadvantage. A couple of students praised the end of affirmative action, which they described as inherently unjust. The dinner officially wrapped up after an hour, but rather than dash out, most students stuck around, continuing the discussion in small clusters.

“A lot of us have memories from college of late-night conversations debating every topic under the sun, and a lot of students have felt as though that’s missing,” UNC’s chancellor, Lee Roberts, said in an interview. Students today, he explained, are looking for “the chance to debate a topic without debating whether you’ve somehow said the wrong thing.”

All this was taking place at CivComm, a residential hall affiliated with a program at UNC called the School of Civic Life and Leadership (SCiLL). The school, which opened in 2023, is part of a larger nationwide civic-thought movement, led by a mix of political conservatives, academic traditionalists and liberals alarmed by progressive overreach. The goal is to push back on what proponents see as an academic culture that has lost sight of the purpose of a liberal arts education—and to do so from within the university. On many campuses, they’ve encountered strong resistance.

Medical Associations Trusted Belief Over Science on Youth Gender Care

The next day, the American Medical Association — which has long approved of such procedures — announced that “in the absence of clear evidence, the A.M.A. agrees with A.S.P.S. that surgical interventions in minors should be generally deferred to adulthood.”

K-12 Tax & $pending Climate: Whitmer budget cuts state worker request after ‘ghost employee’ fight

Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s 2027 budgetproposes the fewest number of state government jobs she has asked the Legislature to fund in four years, despite a request for nearly 1,000 new health department workers to cope with new federal mandates.

Whitmer’s slimmed-down state workforce request suggests that House Speaker Matt Hall’s 2025 war on thousands of funded but unfilled positions in Michigan government is having an impact beyond the 2026 budget, approved last October. That budget funded 1,788 fewer “full-time equivalent” (FTE) positions in state government than were approved for 2025, and 2,670 fewer than Whitmer initially requested for 2026, records from the State Budget Office show.

Words with Spaces

English has hundreds of thousands of compound phrases that name things—not just describe them. “Boiling water” isn’t “water that happens to be boiling.” It’s a hazard, a cooking stage, a state of matter. Yet traditional dictionaries skip almost all of them, because they contain spaces. Merriam-Webster and Oxford cover about 3%.

I got interested in this because I make word games—and wanted to understand which phrases have enough weight to count as vocabulary, and why dictionaries trained us to think they don’t.