The Grace App for Autism helps autistic and other special needs children to communicate effectively, by building semantic sequences from relevant images to form sentences. The app can be easily customized by using picture and photo vocabulary of your choice.

K-12 Tax & Spending Climate: How to Get Rich Just by Moving

What if you could get a 20 percent discount on everything from beer to real estate? You can. You just have to move to Danville, Illinois.

And that’s assuming you live in a town with average prices. Residents of Honolulu and New York, the two most expensive cities in the U.S., would see a 35 percent drop in their cost of living in Danville, according to new data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Feel like moving to Pittsburgh? Now there’s a city in a sweet spot, with cheap prices and, according to new BEA data that adjust average incomes for local inflation, relatively high incomes. Pittsburgh is 6.6 percent cheaper than the national average, and residents are the 36th best-paid in the U.S., bringing home almost $48,000 annually per person.

Locally, Middleton’s property taxes are 16% less than Madison’s for a similar home.

Getting into the Ivies

ASK just about any high school senior or junior — or their parents — and they’ll tell you that getting into a selective college is harder than it used to be. They’re right about that. But the reasons for the newfound difficulty are not well understood.

Population growth plays a role, but the number of teenagers is not too much higher than it was 30 years ago, when the youngest baby boomers were still applying to college. And while many more Americans attend college than in the past, most of the growth has occurred at colleges with relatively few resources and high dropout rates, which bear little resemblance to the elites.

So what else is going on? One overlooked factor is that top colleges are admitting fewer American students than they did a generation ago. Colleges have globalized over that time, deliberately increasing the share of their student bodies that come from overseas and leaving fewer slots for applicants from the United States.

Related: “Financial Aid Leveraging”.

The lowest score – 6% – was in the US

BBC:

William Shakespeare is the UK’s greatest cultural icon, according to the results of an international survey released to mark the 450th anniversary of his birth.

Five thousand young adults in India, Brazil, Germany, China and the USA were asked to name a person they associated with contemporary UK arts and culture.

Shakespeare was the most popular response, with an overall score of 14%.

The result emerged from a wider piece of research for the British Council.

The Queen and David Beckham came second and third respectively. Other popular responses included JK Rowling, Adele, The Beatles, Paul McCartney and Elton John.

Related: wisconsin2.org.

Travel Agents, Technology, and Higher Ed

I am a higher ed technology optimist.

I think that technology will improve higher education.

I believe that we will leverage technology to tackle challenges around costs, access,and quality.

But what if I’m wrong?

What if technology ends up pushing us backwards in higher ed?

One reason why I worry about technology and higher ed is because I like to go on vacation with my family.

To plan our vacations we use technology. Websites to search out destinations. Kayak to find flight. Airbnb to find someplace to stay.

And each year we struggle to find family vacations that will work for everyone. How to satisfy the needs to two teenagers and their parents? What happens when you throw in grandparents? Or younger cousins?

Parent to Obama: Let me tell you about the Common Core test Malia and Sasha don’t have to take but Eva does

We have something very important in common: daughters in the seventh grade. Since your family walked onto the national stage in 2007, I’ve had a feeling that our younger daughters have a lot in common, too. Like my daughter Eva, Sasha appears to be a funny, smart, loving girl, who has no problem speaking her mind, showing her feelings, or tormenting her older sister.

There is, however, one important difference between them: Sasha attends private school, while Eva goes to public school. Don’t get me wrong, I fully support your decision to send Malia and Sasha to private school, where it is easier to keep them safe and sheltered. I would have done the same. But because she is in private school, Sasha does not have to take Washington’s standardized test, the D.C. CAS, which means you don’t get a parent’s-eye view of the annual high-stakes tests taken by most of America’s children.

I have been watching Eva take the Massachusetts MCAS since third grade. To tell you the truth, it hasn’t been a big deal. Eva is an excellent student and an avid reader. She goes to school in a suburban district with a strong curriculum and great teachers. She doesn’t worry about the tests, and she generally scores at the highest level.

Much more on the Common Core, here.

Why (And How) Students Are Learning To Code

Coding is more important now than ever before. With computer related jobs growing at a rate estimated to be 2x faster than other types of jobs, coding is becoming an important literacy for students to have and a more integral part of education and curricula. The handy infographic below takes a look at some of the interesting statistics about coding and computer science jobs. So if you aren’t yet sure why learning to code is important, you’ll find out below. Keep reading to learn more!

Student-Debt Forgiveness Plans Skyrocket, Raising Fears Over Costs, Higher Tuition

Government officials are trying to rein in increasingly popular federal programs that forgive some student debt, amid rising concerns over the plans’ costs and the possibility they could encourage colleges to push tuition even higher.

Enrollment in the plans—which allow students to rack up big debts and then forgive the unpaid balance after a set period—has surged nearly 40% in just six months, to include at least 1.3 million Americans owing around $72 billion, U.S. Education Department records show.

The popularity of the programs comes as top law schools are now advertising their own plans that offer to cover a graduate’s federal loan repayments until outstanding debt is forgiven. The school aid opens the way for free or greatly subsidized degrees at taxpayer expense.

At issue are two federal loan repayment plans created by Congress, originally to help students with big debt loads and to promote work in lower-paying jobs outside the private sector.

A Lack of Affirmative Action Isn’t Why Minority Students Are Suffering

To this end, the Supreme Court’s decision Tuesday in Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action upholding the ban on affirmative action in public-university admissions takes America one step closer to President Kennedy’s dream. In a 6-2 decision, the Court held that a ballot initiative by Michigan residents to bar the use of race preferences as a factor of admission was constitutional.

On a Court that has consistently issued closely contested opinions—often in 5-4 decisions—the overwhelming majority of the Justices recognized the importance and the legality of people in several states like Michigan to prohibit the use of race as a factor in admissions. Despite the commentary to the contrary which is likely to follow in the coming days, the Court did not address whether colleges or universities could use race as a factor of admission—they wisely left the decision to the voters in individual states to make such a decision.

Writing for the majority, Justice Kennedy opined:

Here, the principle that the consideration of race in admissions is permissible when certain conditions are met is not being questioned…. The decision by Michigan voters reflects the ongoing national dialogue about such practices.

Those Master’s-Degree Programs at Elite U

igher education has a long and fraught relationship with the labor market. From colonial colleges training clergymen to the Morrill Act, normal schools, and the great 20th-century expansion of mass higher education, colleges have always been in the business of training people for careers. The oldest university in the Western world, in Bologna, started as a law school. Ask students today why they’re going to college and the most common answer is, by far, “to get a job.”

But most colleges don’t like to see themselves that way. In educators’ own minds, they are communities of scholars above all else. Colleges tend to locate their educational missions among the lofty ideals of the humanities and liberal arts, not the pedestrian tasks of imparting marketable skills.

In part, this reflects the legitimate complexity of some institutional missions. But the fact remains that most professors were hired primarily to teach, most institutions are not research universities, most students are enrolled in preprofessional programs, and, it seems, few colleges have undergraduate curricula that match their supposed commitment to the liberal-arts ideal.

10 Rules for Students and Teachers Popularized by John Cage

One of those whom he inspired was Sister Corita Kent. An unlikely fixture in the Los Angeles art scene, the nun was an instructor at Immaculate Heart College and a celebrated artist who considered Saul Bass, Buckminster Fuller and Cage to be personal friends.

In 1968, she crafted the lovely, touching Ten Rules for Students and Teachers for a class project. While Cage was quoted directly in Rule 10, he didn’t come up with the list, as many website sites claim. By all accounts, though, he was delighted with it and did everything he could to popularize the list. Cage’s lover and life partner Merce Cunningham reportedly kept a copy of it posted in his studio until his dying days. You can check the list out below:

RULE ONE: Find a place you trust, and then try trusting it for a while.

RULE TWO: General duties of a student: Pull everything out of your teacher; pull everything out of your fellow students.

RULE THREE: General duties of a teacher: Pull everything out of your students.

RULE FOUR: Consider everything an experiment.

RULE FIVE: Be self-disciplined: this means finding someone wise or smart and choosing to follow them. To be disciplined is to follow in a good way. To be self-disciplined is to follow in a better way.

Denied University of Michigan hopeful learns tough lesson

First, we should remember that Brooke Kimbrough is still in high school. She is, as the Beatles once sang, just 17.

So even if she ruffled feathers this past week claiming she should have been admitted to the University of Michigan — despite lower grades and test scores — because she is African American and the school needs diversity, the best thing is not to insult her or dismiss her.

The best thing is to talk to her.

So I did. We spoke for a good 45 minutes Friday. I found her passionate, affable, intelligent and, like many teens her age, adamant to make a point but, when flustered, quick to say, “I don’t have all the answers.”

The problem is, she went public as if she did. She was the focus of a U-M rally organized by the advocacy group BAMN (By Any Means Necessary). A clip of her went viral, yelling as if her rights had been denied:

Why 14 Wisconsin high schools take international standardized test

Patricia Deklotz, superintendent of the Kettle Moraine School District, said her district, west of Milwaukee, is generally high performing. But, Deklotz asked, if they talk a lot about getting students ready for the global economy, are they really doing it? PISA is a way to find out.

“It raises the bar from comparing ourselves to schools in Wisconsin,” she said. “This is something that can benchmark us against the world.” Deklotz said she wants the school staff to be able to use the results to analyze how improve their overall practices.

One appeal for taking part in the PISA experiment: The 14 Wisconsin schools didn’t have to pay out of their own pockets.

The Kern Family Foundation, based in Waukesha County, is one of the leading supporters of efforts aimed at improving the global competitiveness of American schoolchildren. Kern convened the invitation-only conference in Milwaukee. And as part of its support of the effort, it is picking up the tab — $8,000 per school — for the 14 schools.

“The Kern Family Foundation’s role is to support and convene organizations focused on improving the rising generation’s skills in math, science, engineering and technology to prepare them to compete in the global marketplace,” Ryan Olson, education team leader at the foundation, said in a statement.

A second somewhat-local connection to the PISA initiative: Shorewood native Jonathan Schnur has been involved in several big ideas in education. Some credit him with sparking the Race to the Top multibillion-dollar competitive education grant program of the Obama Administration. Schnur now leads an organization called America Achieves, which is spearheading the PISA effort.

Until now, Schnur said in an interview, there hasn’t been a way for schools to compare themselves to the rest of the world. Participating in PISA is a way to benefit from what’s being done in the best schools in the world.

Each participating school will get a 150-page report slicing and dicing its PISA results. That includes analysis of not only skills but also what students said in answering questions about how their schools work. Do kids listen to teachers? Do classes get down to business promptly at the start of a period? Do students have good relationships with teachers?

Schleicher told the Milwaukee meeting that PISA asked students why they think some kids don’t do well in math. American students were likely to point to lack of talent as the answer. In higher-scoring countries, students were more likely to say the student hadn’t worked hard enough. “That tells you a lot about the underlying education,” he said.

Related wisconsin2.org. Much more on PISA and Wisconsin’s oft criticized WKCE, here

Child bullying victims still suffering at 50 – study

BBC:

Children who are bullied can still experience negative effects on their physical and mental health more than 40 years later, say researchers from King’s College London.

Their study tracked 7,771 children born in 1958 from the age of seven until 50.

Those bullied frequently as children were at an increased risk of depression and anxiety, and more likely to report a lower quality of life at 50.

Anti-bullying groups said people needed long-term support after being bullied.

A previous study, from Warwick University, tracked more than 1,400 people between the ages of nine and 26 and found that bullying had long-term negative consequences for health, job prospects and relationships.

Learning to Code: The New (Hong Kong) After-School Activity

With the advent of smartphones and handy mobile applications that help you hail a cab or find a gas station, the use of software has become more tightly intertwined with our daily lives. The success stories of some app developers have encouraged students and professionals to learn coding, the language of the future.

Coding class at First Code Academy. First Code Academy

Michelle Sun, a former Goldman Sachs technology analyst decided to take a three-month programming bootcamp at the Hackbright Academy in Silicon Valley after her first mobile application venture failed due to her lack of technical knowledge. Since then she worked as a programmer at Bump, a local-file-sharing app startup later acquired by Google and taught coding in high schools in the Bay Area.

Inspired by her previous employer Joel Gasoigne–the founder of Silicon Valley-based social media management tool Buffer who made the app as a weekend project to meet his own needs to space out his tweets– the Hong Kong native founded a code learning workshop called First Code Academy in Hong Kong last year to pass on lessons she has learned.

Sun spoke about coding in her daily life and the goals of her Hong Kong-based startup First Code Academy. Below are edited excerpts.

There’s more to a good life than college

A smooth hand-off of his department to new owners in St. Louis took eight months. So it was a long goodbye to work he enjoyed and 17 years of friendships.

The transition was doubly difficult because of how he views work. Commit long-term to your employer, he says. Give your absolute best. This is how you live out your calling and live into what comes next.

But where’s next? And what next?

These are my husband’s questions. They are also our son’s questions.

Silas graduates high school next spring and is knee-deep in campus visits and SAT test prep. As he talks aloud about his future, we hear his inner conflict: Do I pursue what I love? I’m not even sure what that is yet. Maybe I should just pick a career that will make me a lot of money.

“When you could pay your way through college by waiting tables, the idea that you should ‘study what interests you’ was more viable than it is today when the cost of a four-year degree often runs to six figures,” wrote Glenn Harlan Reynolds, in an essay for The Wall Street Journal.

Our son worries about choosing the wrong path. No more are the 20s the years of do-overs.

The Sad Demise of Collegiate Fun

A few years ago, the psychologist Peter Gray released a fascinating—and sobering—study: Lack of free play in millennials’ overscheduled lives is giving kids anxiety and depression in record numbers. Why? They’re missing what Gray’s generation (and mine) had: “Time to explore in all sorts of ways, and also time to become bored and figure out how to overcome boredom, time to get into trouble and find our way out of it.”

What happens when a bunch of anxious kids who don’t know how to get into trouble go to college? A recent trip back to my beloved alma mater, Vassar—combined with my interactions with students where I teach and some disappointing sleuthing—has made it apparent that much of the unstructured free play at college seems to have disappeared in favor of pre-professional anxiety, coupled with the nihilistic, homogeneous partying that exists as its natural counterbalance. The helicopter generation has gone to college, and the results might be tragic for us all.

I certainly noticed a toned-down version of this trend at Vassar, which in my day was where you went to get seriously weird (all right, not Bennington-weird or Hampshire-weird, but weird). A lot about the place was the same—interesting, inquisitive students; dedicated faculty; caring administrators—but it was also dead all weekend! The closest I saw to free play time was, I kid you not, a Quidditch game.

Whether it’s bikes or bytes, teens are teens

If you’re like most middle-class parents, you’ve probably gotten annoyed with your daughter for constantly checking her Instagram feed or with your son for his two-thumbed texting at the dinner table. But before you rage against technology and start unfavorably comparing your children’s lives to your less-wired childhood, ask yourself this: Do you let your 10-year-old roam the neighborhood on her bicycle as long as she’s back by dinner? Are you comfortable, for hours at a time, not knowing your teenager’s exact whereabouts?

What American children are allowed to do — and what they are not — has shifted significantly over the last 30 years, and the changes go far beyond new technologies.

If you grew up middle-class in America prior to the 1980s, you were probably allowed to walk out your front door alone and — provided it was still light out and you had done your homework — hop on your bike and have adventures your parents knew nothing about. Most kids had some kind of curfew, but a lot of them also snuck out on occasion. And even those who weren’t given an allowance had ways to earn spending money — by delivering newspapers, say, or baby-sitting neighborhood children.

All that began to change in the 1980s. In response to anxiety about “latchkey” kids, middle- and upper-class parents started placing their kids in after-school programs and other activities that filled up their lives from morning to night. Working during high school became far less common. Not only did newspaper routes become a thing of the past but parents quit entrusting their children to teenage baby-sitters, and fast-food restaurants shifted to hiring older workers.

Mother wishes she had restricted flow of prescription drugs to her son

Looking back, Pam Herrera wishes she had asked more questions and been more forceful with her son’s therapists.

The list of medications her son took ages 4-16 is staggering: multiple antipsychotics, antidepressants and stimulants, sometimes five at a time, each at the maximum dose allowed. He was so medicated, Herrera said, “we disintegrated his ability to learn.”

The Herreras, foster parents to more than 100 children over the past 18 years, first met Anthony when he was 15 months old. He was so neglected and malnourished that he could not sit up or eat solid food.

They adopted him in 1998, when he was 3, and for the next several years struggled to control behavior so violent and out of control that it took over their lives.

The home-school conundrum Meeting the German Christians who claimed asylum in America

Civil disobedience does not come easily to Morristown, a conservative spot of almost 30,000 souls. Yet city fathers swore to endure jail time, if necessary, to shield Uwe Romeike, his wife Hannelore and their seven children, from federal agents with orders to expel them from Morristown, where they have lived since fleeing Baden-Württemberg in 2008. A stand-off seemed likely when, on March 3rd, the Supreme Court declined to hear a final appeal against the Romeikes’ expulsion, handing victory to the American government, which had always rejected the family’s claims to be refugees from religious and social persecution. However, a day later federal officials put the family’s deportation on indefinite hold—thereby allowing them to stay without setting a legal precedent (and without insulting Germany, a close ally).

German laws forbid parents from educating their children at home in almost all cases, citing society’s interest in avoiding closed-off “parallel societies”. Germany’s highest court calls schools the best place to bring together children of different beliefs and values, in the name of “lived tolerance”. In plainer language, the Romeikes believe that, if they return to Germany, their children face being taken to school by force. This happened in 2006: the youngsters wept as they were driven away in a police van. (On the next school morning supporters showed up and officers backed off.) Worse, their children might be taken into care—this is the family’s greatest fear, prompting their flight from Germany. As the Romeikes scanned the globe for options, the Home School Legal Defence Association, a Virginia-based group, urged them to apply for asylum in America. The hope was to cause a fuss in the press, says an HSLDA lawyer, Michael Donnelly, and to “fuel the flame of liberty in Germany”.

‘Selfie’ body image warning issued

Spending lots of time on Facebook looking at pictures of friends could make women insecure about their body image, research suggests.

The more women are exposed to “selfies” and other photos on social media, the more they compare themselves negatively, according to a study.

Friends’ photos may be more influential than celebrity shots as they are of known contacts, say UK and US experts.

The study is the first to link time on social media to poor body image.

The mass media are known to influence how people feel about their appearance.

But little is known about how social media impact on self-image.

Students could be paying loans into their 50s

Most students will still be paying back loans from their university days in their 40s and 50s, and many will never clear the debt, research finds.

Almost three-quarters of graduates from England will have at least some of their loan written off, the study, commissioned by the Sutton Trust, says.

The trust says the 2012 student finance regime will leave people vulnerable at a time when family costs are at a peak.

Ministers said more students from less advantaged homes were taking up places.

The study, written by researchers at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), assessed the impact of the new student loan system for fees and maintenance, introduced in England from September 2012 to coincide with higher tuition costs of up to £9,000 a year.

The study – entitled Payback Time? – found that a typical student would now leave university with “much higher debts than before”, averaging more than £44,000.

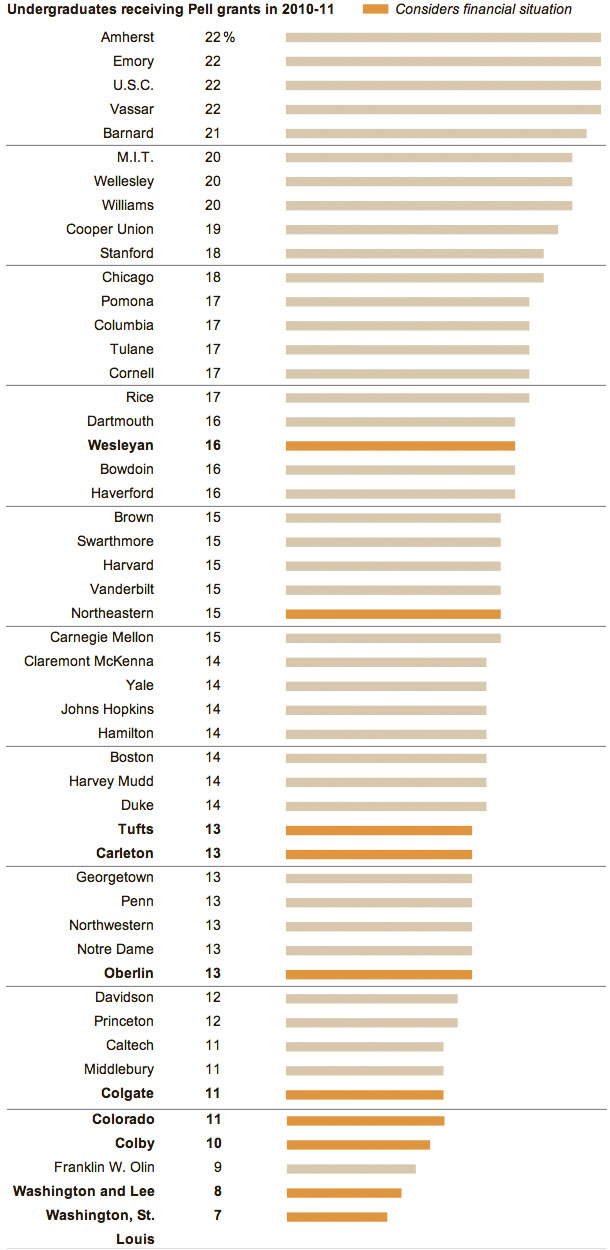

Wesleyan bucks trend, lets students graduate in 3 years

They’ve given up on studying abroad, taking a summer vacation, or getting a full night’s sleep. Cookies or a granola bar on the run often constitute meals. Friends give them guilt trips for skipping out on the senior year bonding experience.

But for a few students at Wesleyan University seeking to earn a degree in three years, there will be a big payoff: saving tens of thousands of dollars in tuition.

Wesleyan, a liberal arts college sometimes called a “little Ivy,” appears to be the most elite school yet to embrace the idea of helping students cut down on the exorbitant cost of a college education by speeding up their journey to graduation.

The sheer enormity of tuition prices has helped the concept of a three-year bachelor’s degree gain a foothold in recent years at a few dozen schools around the country, including the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Lesley University.

The number of students choosing to participate remains tiny at most of the colleges, because of the difficulty of doing so and the enduring allure of four years in the ivory tower. And some educators worry that three years isn’t enough time for young people to find themselves intellectually or emotionally. But the endorsement from Wesleyan (sticker price $61,000 a year) may yet help popularize the idea.

Public Schools Can’t Help but Curb Freedom of Expression

It was trending on Twitter all day on Tuesday: #ReligiousFreedomForAll. The impetus was the Sebelius v. Hobby Lobby case being argued before the Supreme Court, and disgust over government forcing people to pay for medical treatments they find immoral. But if people cared about public schooling as much as they do Obamacare, hashtags defending all kinds of freedom would be the daily norm on Twitter.

Just like Obamacare, public schools — government institutions for which all people must pay — regularly violate basic rights. They have to: Among many curbs on freedom, to avoid chaos schools have to have rules about what students and teachers can say, and decisions must be made about what is — and is not — taught.

Consider the nationally covered Easton Area School District v. B.H. case (colloquially known as “I (Heart) Boobies”), which the Supreme Court refused to hear a few weeks ago. It involved two students in Easton, PA, who were suspended for wearing pink, breast-cancer-awareness bracelets that carried the “boobies” message. The district argued that the bracelets, with their intentionally attention-grabbing message, threatened school“decorum” and “the civility of discussion in the classroom.”

How to get British kids reading

Pavan’s favourite activity is playing football outdoors. His second favourite is playing football indoors, and in third place is practising football skills against the sofa. Reading – the pursuit that Francis Bacon claimed “maketh a full man” – comes further down the eight-year-old’s list, behind school, going to discos, buying stuff, chatting to people, watching TV and playing on his Xbox games console.

Would he ever pick up a book for pleasure? “No,” Pavan shoots back jovially. “If I’m bored, I will ask my mum if I can play on her phone.” By this point, I am relieved that Michael Gove is not part of our conversation at a homework club in Harlesden Library, north London.

The UK education secretary has long feared that British children are “just not reading enough”. The same concern has been raised by publishers and literacy charities, which worry that new distractions – computer games, online videos, social networking – are pushing books off the shelf. More than 60 per cent of 18-to-30-year-olds now prefer watching television or DVDs to reading, according to a survey for the charity Booktrust. A similar proportion of young people think the internet and computers will replace books in the next 20 years.

The literacy debate received fresh impetus last October when a study from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development suggested that vast numbers of young people were leaving school without the ability to read well. Of the 24 industrialised countries covered by the research, England was the only one that went backwards, with literacy and numeracy skills lower among the young – those aged 16 to 24 – than the old. (The results were little better in Northern Ireland; Scotland and Wales were not included in the study.)

An Update on Credit for Non Madison School District Courses; Instructional Policy Changes

The Madison School District (PDF):

Effective July 1, 2016, increase math and science graduation requirements by 1 credit each and eliminate specific math course requirements

Remove references to the High School Graduation Test (HGST)

Add language permitting course equivalencies

Related: notes and links on Credit for non-Madison School District courses.

Appealing to a College for more Financial Aid

The era of the financial aid appeal has arrived in full, and April is the month when much of the action happens.

For decades, in-the-know families have gone back to college financial aid officers to ask for a bit more grant money after the first offer arrived. But word has spread, and the combination of the economic collapse in 2008-9 and the ever-rising list price for tuition and expenses has led to a torrent of requests for reconsideration each spring.

Do not call it bargaining. Or negotiation. That makes financial aid officers mad, as they don’t like to think of themselves as presiding over an open-air bazaar. But that’s not to say that you shouldn’t ask. At many of the private colleges and universities that students insist on shooting for, half or more of families who appeal get more money. And this year, for the first time, the average household income of financial aid applicants will top $100,000 at the 163 private colleges and universities that the consulting firm Noel-Levitz tracks.

Report looks at earning potential of RI graduates

A new report from the Rhode Island Campaign for Achievement Now looks at the state’s education system.

Christine Lopes of RI-CAN said Thursday that the group looks at statewide date to measure trends and outcomes.

This is the fourth report generated in four years, and this year a focus is on earning power for students who graduate from a high school in Rhode Island.

“We found that a high school graduate in Rhode Island can earn about $25,000 a year. What’s even more startling is there’s a $40,000 a year gap between a student who graduates high school and a student that has a bachelor’s or higher,” Lopes said.

State Education Commission Deborah Gist said she wasn’t completely surprised by that.

Prediction: No commencement speaker will mention this – the huge gender degree gap for the Class of 2014 favoring women

Now that we’re about a month away from college graduation season, I thought it would be a good time to show the updated chart above of the huge college degree gap by gender for the upcoming College Class of 2014 (data here). Based on Department of Education estimates, women will earn a disproportionate share of college degrees at every level of higher education in 2014 for the ninth straight year. Overall, women in the Class of 2014 will earn 140 college degrees at all levels for every 100 men, and there will be a 638,200 college degree gap in favor of women for this year’s class (2.21 million total degrees for women vs. 1.57 million total degrees for men). By level of degree, women will earn: a) 160 associate’s degrees for every 100 men, b) 130 bachelor’s degrees for every 100 men, 149 master’s degrees for every 100 men and 106 doctoral degrees for every 100 men.

Over the next decade, the gender disparity for college degrees is expected to increase according to Department of Education forecasts, so that by 2022, women will earn 148 college degrees for every 100 degrees earned by men, with especially huge gender imbalances in favor of women for associate’s degrees (162 women for every 100 men) and master’s degrees (162 women for every 100 men).

What happens to all the Asian-American overachievers when the test-taking ends?

I understand the reasons Asian parents have raised a generation of children this way. Doctor, lawyer, accountant, engineer: These are good jobs open to whoever works hard enough. What could be wrong with that pursuit? Asians graduate from college at a rate higher than any other ethnic group in America, including whites. They earn a higher median family income than any other ethnic group in America, including whites. This is a stage in a triumphal narrative, and it is a narrative that is much shorter than many remember. Two thirds of the roughly 14 million Asian-Americans are foreign-born. There were less than 39,000 people of Korean descent living in America in 1970, when my elder brother was born. There are around 1 million today.

Asian-American success is typically taken to ratify the American Dream and to prove that minorities can make it in this country without handouts. Still, an undercurrent of racial panic always accompanies the consideration of Asians, and all the more so as China becomes the destination for our industrial base and the banker controlling our burgeoning debt. But if the armies of Chinese factory workers who make our fast fashion and iPads terrify us, and if the collective mass of high-achieving Asian-American students arouse an anxiety about the laxity of American parenting, what of the Asian-American who obeyed everything his parents told him? Does this person really scare anyone?

Earlier this year, the publication of Amy Chua’s Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother incited a collective airing out of many varieties of race-based hysteria. But absent from the millions of words written in response to the book was any serious consideration of whether Asian-Americans were in fact taking over this country. If it is true that they are collectively dominating in elite high schools and universities, is it also true that Asian-Americans are dominating in the real world? My strong suspicion was that this was not so, and that the reasons would not be hard to find. If we are a collective juggernaut that inspires such awe and fear, why does it seem that so many Asians are so readily perceived to be, as I myself have felt most of my life, the products of a timid culture, easily pushed around by more assertive people, and thus basically invisible?

Maybe paying for good grades is not so bad

I have been compiling data on college-level courses and exams at every public high school in the Washington area since 1998. It’s fun, like collecting baseball cards. Sometimes schools make progress. Sometimes they slip. Sometimes I find weird and exciting statistical jumps.

This year, the numbers from Stafford County triggered my curiosity. Three of its schools had big increases in Advanced Placement tests given last May. Those are difficult three-hour exams at the end of tough courses. Many students who would do well in them don’t take them, even though they help prepare for college. But at Colonial Forge High School, the number of AP tests jumped 25 percent. Tests at North Stafford High were up 56 percent. At Stafford High, the increase was 105 percent, from 543 to 1,113 tests. The passing rates declined slightly from the previous year, but the number of tests with passing scores was much higher.

Elementary Financial Literacy: Lesson Ideas and Resources

My daughter is in elementary school. She hates math, but she loves to count her own money! I have used her allowance to help bring basic mathematics alive, including some of the lessons created by the U.S. President’s Advisory Council on Financial Capability exhibited on the website Money As You Grow. These are 20 essential, age-appropriate financial lessons — with corresponding activities — written explicitly for parents. At a time when parents are most involved with their children’s lives, this is an ideal resource to engage them about teaching money management skills at home.

Schools are beginning to partner with organizations and provide matched savings programs, which enlist donors to make contributions to low-income children’s college accounts. My dream would be to see these opportunities available for every student. I doubt that matched savings programs in our elementary schools are scalable in the immediate future, but they may be in the years that lie ahead. Research has found that such opportunities lead to improvements in knowledge and attitudes toward money.

However, schools don’t need a matched savings program partner to integrate financial literacy skills. As you will read below, there are a number of ways that financial literacy can be integrated into English and mathematics.

Celebrate? Sorry, We’re Studying

On the eve of their West Regional final Saturday against Arizona, the Wisconsin players were ensconced in a hotel down the street from Disneyland, in a meeting room with two walls of floor-to-ceiling windows.

In the fishbowl that is the N.C.A.A. men’s basketball tournament, temptation was giving the Badgers a full-court press. Outside, Wisconsin fans basking in the bright sunshine strolled past in shorts, red T-shirts and halter tops. A few held beer cans, including a woman who rapped on a window until the players looked up.

The basketball portion of their day was done, but the Badgers had more business to tend to. They put their heads down and resumed studying, ignoring the foot traffic outside, the chocolate chip cookies left over from the lunch buffet and the officials’ whistles coming from the television, tuned to a regional game featuring their Big Ten rival Michigan, filtering in from the lobby bar on the other side of the double doors.

When one New Zealand school tossed its playground rules and let students risk injury, the results were surprising

It was a meeting Principal Bruce McLachlan awaited with dread.

One of the 500 students at Swanson School in a northwest borough of Auckland had just broken his arm on the playground, and surely the boy’s parent, who had requested this face-to-face chat with its headmaster, was out for blood.

It had been mere months since the gregarious principal threw out the rulebook on the playground of concrete and mud, dotted with tall trees and hidden corners; just weeks since he had stopped reprimanding students who whipped around on their scooters or wielded sticks in play sword fights.

He knew children might get hurt, and that was exactly the point — perhaps if they were freed from the “cotton-wool” in which their 21st century parents had them swaddled, his students may develop some resilience, use their imaginations, solve problems on their own.

The parent sat down, stone-faced, across from the principal.

“‘My son broke his arm in the playground, and I just want to make sure…” he began.

“And I’m thinking ‘Oh my God, what’s going to happen?’” Mr. McLachlan recalled, sitting in his “fishbowl” of an office one hot Friday afternoon last month.

The parent continued: “I just wanted to make sure you don’t change this play environment, because kids break their arms.”

Will You Obey Your Robot Boss?

People are always joking about our robot overlords, but before robots become the world’s rulers, they’re probably going to be our bosses at work first. Either way, it’s important to know how pliable we humans are going to be.

Researchers at the University of Manitoba were curious about how far people would go in obeying the commands of a robot, so they designed an experiment that echoes Stanley Milgram’s infamous obedience studies, in which many participants obeyed an authority figure who told them to administer painful electrical shocks to strangers.

Substitute a small but slightly evil-sounding humanoid robot for the lab-coated researcher, and give the participants a really, really boring task rather than a morally fraught one, and you have the set up below. It’s actually a little uncomfortable to watch.

The Drugging of the American Boy

By the time they reach high school, nearly 20 percent of all American boys will be diagnosed with ADHD. Millions of those boys will be prescribed a powerful stimulant to “normalize” them. A great many of those boys will suffer serious side effects from those drugs. The shocking truth is that many of those diagnoses are wrong, and that most of those boys are being drugged for no good reason—simply for being boys. It’s time we recognize this as a crisis.

If you have a son, you have a one-in-seven chance that he has been diagnosed with ADHD. If you have a son who has been diagnosed, it’s more than likely that he has been prescribed a stimulant—the most famous brand names are Ritalin and Adderall; newer ones include Vyvanse and Concerta—to deal with the symptoms of that psychiatric condition.

The Drug Enforcement Administration classifies stimulants as Schedule II drugs, defined as having a “high potential for abuse” and “with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence.” (According to a University of Michigan study, Adderall is the most abused brand-name drug among high school seniors.) In addition to stimulants like Ritalin, Adderall, Vyvanse, and Concerta, Schedule II drugs include cocaine, methamphetamine, Demerol, and OxyContin.

Paying for the Party

The authors lived for a year in a “party” dorm in a large midwestern flagship public university (not mine) and kept up with the women in the dorm till after they had graduated college. The thesis of the book is that the university essentially facilitates (seemingly knowingly, and in some aspects strategically) a party pathway through college, which works reasonably well for students who come from very privileged backgrounds. The facilitatory methods include: reasonably scrupulous enforcement of alcohol bans in the dorms (thus enhancing the capacity of the fraternities to monopolize control of illegal drinking and, incidentally, forcing women to drink in environments where they are more vulnerable to sexual assault); providing easy majors which affluent students can take which won’t interfere with their partying, and which will lead to jobs for them, because they have connections in the media or the leisure industries that will enable them to get jobs without good credentials; and assigning students to dorms based on choice (my students confirm that dorms have reputations as party, or nerdy, or whatever, dorms that ensure that they retain their character over time, despite 100% turnover in residents every year).

The problem is that other students (all their subjects are women), who do not have the resources to get jobs in the industries to which the easy majors orient them, and who lack the wealth to keep up with the party scene, and who simply cannot afford to have the low gpas that would be barriers to their future employment, but which are fine for affluent women, get caught up in the scene. They are, in addition, more vulnerable to sexual assault, and less insulated (because they lack family money) against the serious risks associated with really screwing up. The authors tell stories of students seeking upward social mobility switching their majors from sensible professional majors to easy majors that lead to jobs available only through family contacts, not through credentials. Nobody is alerting these students to the risks they are taking. So the class inequalities at entry are exacerbated by the process. Furthermore, the non-party women on the party floor are, although reasonably numerous, individually isolated—they feel like losers, not being able to keep up with the heavy demands of the party scene. The authors document that the working class students who thrive are those who transfer to regional colleges near their birth homes.

Reports of a Drop in Childhood Obesity Are Overblown

It is no secret that the United States has a weight problem. Roughly 30 percent of American adults are clinically obese, or have a body mass index of at least 30. That’s more than 175 pounds for someone who’s 5 foot 4, the average height of an American woman; or more than 203 pounds for someone who’s 5 foot 9, the average height of an American man. Obesity is associated with a whole host of health issues — diabetes, sleep apnea, stroke, heart attack and on and on — meaning that for many of us, diet is the real killer.

Obesity rates have risen over time, especially in children. The disease we now refer to as Type 2 diabetes used to be called “adult-onset diabetes.” One of the main reasons for the name change is that the onset became increasingly common in children, caused by obesity.

With this backdrop, the headlines last month about declines in childhood obesity were remarkable and encouraging. Here’s how The New York Times described it: “Obesity Rate in Young Children Plummets 43% in a Decade.” This and other articles went on to describe a huge decrease — from 13.9 percent to 8.4 percent — in the obesity rate for children between the ages of 2 and 5. The articles cited all sorts of reasons for the drop, including that kids are drinking less soda and that more mothers are engaged in breastfeeding. First lady Michelle Obama’s push for kids to exercise more and eat healthier foods also got credit.

“we don’t believe now is the time to move individual (charter school) proposals forward” – Madison Superintendent

Madison Superintendent Jennifer Cheatham (3MB PDF):

While we are busy working in the present day on the improvement of all of our schools, a key aspect of our long-term strategy must include the addition or integration of unique programs or school models that meet identified needs. However, to ensure that these options are strategic and that they enhance our focus rather than distract from it, we need to build a comprehensive and thoughtful strategy.

We need to think in depth about how options like additional district charter schools would meet the needs of our students, how they would support our vision and close opportunity gaps for all. The things we are learning now from our high school reform collaborative, which was just launched, and the review of our special education and alternative programs, which is now in progress, will be powerful information to help build that strategy over the coming school year.

Until we establish that more comprehensive long-term strategy, together with the Board and with direction and input from our educators and families, we don’t believe now is the time to move individual proposals forward. Both the district and those proposing a charter option should have the guidance of a larger strategy to ensure that any proposal would meet the needs of our students and accomplish our vision.

Related: A majority of the Madison School Board rejected the proposed Madison Preparatory Academy IB Charter School. Also, the proposed (and rejected) Studio School.

Race, gender, schooling and university success – six key charts

Does any part of how you are born and raised mean you are more likely to be successful after reaching university?

A report by the Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) looked at how students from a variety of different backgrounds performed at English universities after entering a full-time degree course in 2007-08.

The key element of the analysis is seeing which students were more likely to achieve first or upper second class honours than others who have the same A-Level results but come from different backgrounds.

Each of the charts below is broken down by A-Level grades so the left-hand side shows how those with the highest marks performed compared to those on the right hand side who had the lowest marks.

Check out the terrible paper that earned a player an A- at North Carolina

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is one of our nation’s finest universities, ranking 30th in the latest U.S. News and World Report list of top schools and eighth on Forbes’ list of top public colleges. And the bit of drivel above apparently earned an A-minus, according to ESPN.

Why? Simple. That paper was written by an athlete for a class specifically designed to keep them moving through the university.

“Athletes couldn’t write a paper,” Mary Willingham, a specialist in the school’s learning-support system-turned-whistleblower, told ESPN. “They couldn’t write a paragraph. They couldn’t write a sentence yet.” She said that some of the students were reading at a second- or third-grade level, which is considered illiterate for a college-age student. As Willingham notes, in the “AFAM” classes, players were notching As and Bs, but in actual classes such as Biology and Economics were receiving Ds and Fs.

Blaming Poverty On Culture Is Not A Solution

Blaming poverty on the mysterious influence of “culture” is a convenient excuse for doing nothing to address the problem.

That’s the real issue with what Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., said about distressed inner-city communities. Critics who accuse him of racism are missing the point. What he’s really guilty of is providing a reason for government to throw up its hands in mock helplessness.

The fundamental problem that poor people have, whether they live in decaying urban neighborhoods or depressed Appalachian valleys or small towns of the Deep South, is not enough money.

Unpaid student loans ‘a fiscal time bomb for universities’

The university sector is facing a “fiscal time bomb”, the chairman of the Commons business committee has warned, after it was revealed that the government has dramatically revised down the proportion of student debt that will ever be repaid.

Adrian Bailey said the Treasury needed to face up to the problem, after David Willetts, the universities minister, revealed the rate of non-repayment of student loans is near the point at which experts believe tripling tuition fees will add nothing to Treasury coffers.

Bailey said: “There is a huge potential black hole in the government’s budget figures. You’ve got all these confident predications about budget deficit falling and right in the middle of that is a potential fiscal time bomb that doesn’t seem to have been addressed.”

How Art History Majors Power the U.S. Economy

There’s nothing like a bunch of unemployed recent college graduates to bring out the central planner in parent-aged pundits.

In a recent column for Real Clear Markets, Bill Frezza of the Competitive Enterprise Institute lauded the Chinese government’s policy of cutting financing for any educational program for which 60 percent of graduates can’t find work within two years. His assumption is that, because of government education subsidies, the U.S. is full of liberal-arts programs that couldn’t meet that test.

“Too many aspiring young museum curators can’t find jobs?” he writes. “The pragmatic Chinese solution is to cut public subsidies used to train museum curators. The free market solution is that only the rich would be indulgent enough to buy their kids an education that left them economically dependent on Mommy and Daddy after graduation.” But, alas, the U.S. has no such correction mechanism, so “unemployable college graduates pile up as fast as unsold electric cars.”

The boy whose brain could unlock autism

SOMETHING WAS WRONG with Kai Markram. At five days old, he seemed like an unusually alert baby, picking his head up and looking around long before his sisters had done. By the time he could walk, he was always in motion and required constant attention just to ensure his safety.

“He was super active, batteries running nonstop,” says his sister, Kali. And it wasn’t just boyish energy: When his parents tried to set limits, there were tantrums—not just the usual kicking and screaming, but biting and spitting, with a disproportionate and uncontrollable ferocity; and not just at age two, but at three, four, five and beyond. Kai was also socially odd: Sometimes he was withdrawn, but at other times he would dash up to strangers and hug them.

Things only got more bizarre over time. No one in the Markram family can forget the 1999 trip to India, when they joined a crowd gathered around a snake charmer. Without warning, Kai, who was five at the time, darted out and tapped the deadly cobra on its head.

Large majority opposes paying NCAA athletes, Washington Post-ABC News poll finds

A new Washington Post-ABC News poll finds that a large majority of the general public opposes paying salaries to college athletes beyond the scholarships currently offered.

Only 33 percent support paying college athletes. At 64 percent, opposition is nearly twice as high as support, with 47 percent strongly against the idea. Nearly every demographic and political group opposes it except non-whites, for whom 51 percent support. The breakdown among whites (73 percent oppose, 24 percent support) tilted strongly in the opposite direction, echoing the perspective of NCAA President Mark Emmert.

“We have long heard from fans that there is little support for turning student-athletes into paid employees of their universities,” Emmert said in a statement. “The overwhelming majority of student-athletes, across all sports, play college athletics as part of their educational experience and for the love of their sport — not to be paid a salary.”

Tiger Couple Gets It Wrong on Immigrant Success

The Triple Package: How Three Unlikely Traits Explain the Rise and Fall of Cultural Groups in America

Amy Chua and Jed Rubenfeld

Penguin, $27.95The tiger couple is chasing its own tail, which is to say, they are stuck in circular reasoning. In their new book, The Triple Package, Amy Chua, author of the best-selling Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, and Jed Rubenfeld tackle the question of why certain groups are overrepresented in the pantheon of success. They postulate the reason for their success is that these groups are endowed with “the triple package”: a superiority complex, a sense of insecurity, and impulse control. The skeptic asks, “How do we know that?” To which they respond: “They’re successful, aren’t they?”

But Chua and Rubenfeld proffer no facts to show that their exemplars of ethnic success—Jewish Nobel Prize winners, Mormon business magnates, Cuban exiles, Indian and Chinese super-achievers—actually possess this triple package. Or that possessing these traits is what explains their disproportionate success. For that matter, they do not demonstrate that possessing the triple package is connected, through the mystical cord of history, to Jewish sages, Confucian precepts, or Mormon dogma. Perhaps, as critics of Max Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism have contended, success came first and only later was wrapped in the cloth of religion. In other words, like elites throughout history, Chua and Rubenfeld’s exemplars enshroud their success in whatever system of cultural tropes was available, whether in the Talmud, Confucianism, Mormonism, or the idolatry of White Supremacy. The common thread that runs through these myths of success is that they provide indispensable legitimacy for social class hierarchy.

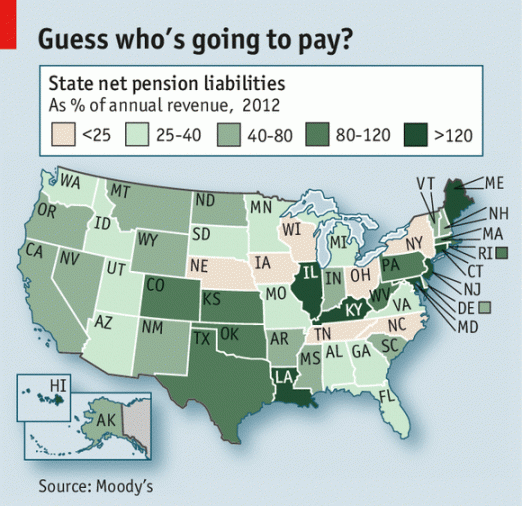

k-12 Tax & Spending Climate: Rhode Island Public Sector Pension Reform

WHEN Central Falls—a city of 19,000 people squeezed into barely one square mile—filed for bankruptcy in 2011, it sent shivers across Rhode Island and America. Some retired civil servants saw their pensions cut from $27,000 a year to $12,000. To stop the state from heading in the same direction, Gina Raimondo, its treasurer (pictured), launched a campaign to overhaul Rhode Island’s pension system, one of many that is in deep trouble (see map). She went from town to town explaining why change was needed, earning a reputation as a fiscally responsible Democrat with a bright political future. The legislature passed reforms in November 2011.

Stop the Glorification of Busy

Chio:

I didn’t realize it was time for finals until I read the Facebook status updates. My newsfeed was littered with posts discussing immense sleep deprivation; pictures of meals comprised of Hot Cheetos, Red Bulls, and 5-Hour Energy drinks; and extensive lists of extracurricular activities that needed to be accomplished, alongside finals, in a ridiculously short amount of time. I’m no longer in college, so I was able to look at this with an outsider’s lens and what I saw astounded me. It was ridiculous. I was bothered by how the practices, and consequences, of busyness were glorified. Students wrote about them as if they were embarking on a fruitful challenge: maxing out the total credits they could take, being involved in every club, not sleeping. They would reap the rewards of A’s today and impressive resumes later, the health of their bodies not even considered. Several months ago, I was doing the exact same thing.

In fact, I was probably the perfect illustration of the situation I am describing. By my senior year, I was managing student government, acting in a play, teaching a class, taking 20 credits, being in a research program, trying to bring about revolution…you get the idea. My mind was proud of my accomplishments, but my body suffered the consequences. It became so difficult to sleep that I required sleeping pills. I had panic attacks, which I never had before. My back and head were constantly hurting from tension. The food I was eating did not feel good in my body.

Maybe it was my overachieving self. Maybe it was my inferiority complex as a poor womyn of color who doubted whether she was good enough. Who was trying to ensure she was a good job candidate to help her family pay rent they couldn’t afford. Who dreamed of graduate school, but was unsure of what it looked like or how to get there. Who tried to shout, “Fuck you!” to stereotypes and barriers. Who was trying to bring change NOW because she was impatient and tired of experiencing oppression.

‘Intelligent people are more likely to trust others’

Intelligent people are more likely to trust others, while those who score lower on measures of intelligence are less likely to do so, says a new study. Oxford University researchers based their finding on an analysis of the General Social Survey, a nationally representative public opinion survey carried out in the United States every one to two years. The authors say one explanation could be that more intelligent individuals are better at judging character and so they tend to form relationships with people who are less likely to betray them. Another reason could be that smarter individuals are better at weighing up situations, recognising when there is a strong incentive for the other person not to meet their side of the deal.

The study, published in the journal, PLOS ONE, supports previous research that analysed data on trust and intelligence from European countries. The authors say the research is significant because social trust contributes to the success of important social institutions, such as welfare systems and financial markets. In addition, research shows that individuals who trust others report better health and greater happiness.

Homework’s Emotional Toll on Students and Families

When your children arrive home from school this evening, what will be your first point of conflict? How’s this for an educated guess? Homework.

Do they have any? How much? When are they going to do it? Can they get it done before practice/rehearsal/dinner? After? When is it due? When did they start it? Even parents who are wholly hands off about the homework itself still need information about how much, when and how long if there are any family plans in the offing — because, especially for high school students in high-performing schools, homework has become the single dominating force in their nonschool lives.

Researchers asked 4,317 students from 10 high-performing high schools in upper-middle-class California communities to describe the impact of homework on their lives, and the results offer a bleak picture that many of us can see reflected around our dining room tables. The students reported averaging 3.1 hours of homework nightly, and they added comments like: “There’s never a break. Never.”

Netflix’s Reed Hastings: “Get Rid of Elected School Boards”

On March 4th, 2014, Billionaire Netflix CEO, Reed Hastings delivered the keynote speech to the California Charter School Association’s annual conference. In that keynote speech, Mr. Hastings made a shocking statement: Democratically elected school board members are the problem with education, and they must be replaced by privately held corporations in the next 20-30 years.

Reed Hastings has just over a billion dollars, riches built on software companies and the entertainment giant Netflix. Mr. Hastings also sat on the California State Board of Education from 2000 to 2004, when he stepped down amid controversy.

Hastings, who sits on Rocketship’s national strategy advisory board, has invested millions in Rocketship. He’s also made significant political action committee contributions on Rocketship’s behalf, most recently, he poured $50,000 into a PAC to support pro-charter Santa Clara County Office of Education members.

Choosing to Learn: Self Government or “central planning”, ie, “We Know Best”

Joseph L. Bast, Lindsey Burke, Andrew J. Coulson, Robert C. Enlow, Kara Kerwin & Herbert J. Walberg:

Americans face a choice between two paths that will guide education in this nation for generations: self-government and central planning. Which we choose will depend in large measure on how well we understand accountability.

To some, accountability means government-imposed standards and testing, like the Common Core State Standards, which advocates believe will ensure that every child receives at least a minimally acceptable education. Although well-intentioned, their faith is misplaced and their prescription is inimical to the most promising development in American education: parental choice.

True accountability comes not from top-down regulations but from parents financially empowered to exit schools that fail to meet their child’s needs. Parental choice, coupled with freedom for educators, creates the incentives and opportunities that spur quality. The compelled conformity fostered by centralized standards and tests stifles the very diversity that gives consumer choice its value.

Well Worth Reading.

The Achievement Gap as Seen Through the Eyes of a Student

Robin Mwai and Deidre Green

Simpson Street Free Press

The achievement gap is very prevalent in my school on a day-to-day basis. From the lack of minority students taking honors classes, to the over abundance of minority students occupying the hallways during valuable class time, the continuously nagging minority achievement gap prevails.

Upon entering LaFollette High School, there are visible traces of the achievement gap all throughout the halls. It seems as if there is always a presence of a minority student in the hallway no matter what the time of day. At any time during the school day there are at least 10 to 15 students, many of whom are minorities, wandering the halls aimlessly. These students residing in the halls are either a result of getting kicked out of class due to behavior issues, or for some, the case may be that they simply never cared to go to class at all. This familiar scene causes some staff to assume that all minority students that are seen in the halls during class time are not invested in their education. These assumptions are then translated back to the classroom where teachers then lower their expectations for these students and students who appear to be like them.

While there are some students of color who would rather spend their school time in the halls instead of in the classroom, others wish for the opportunity to be seen as focused students. Sadly many bright and capable minority students are being overlooked because teachers see them as simply another unmotivated student to be pushed through the system. Being a high achieving minority student in the Madison school District continues to be somewhat of a rarity–even in 2014. Three out of the four classes I am taking this semester at La Follette High School, which uses the four-block schedule, are honors or advanced courses. Of the 20 to 25 students in those honors classes, I am one of a total of two minority students enrolled.

Even though a large percentage of the student body is made up of minority students, very few of theses students are taking honors or advanced classes. These honors courses provide students with necessary skills that help prepare them for college. These skills include: critical thinking, exposure to a wider variety of concepts, and an opportunity to challenge their own mental capacities in ways that non-honors courses don’t allow. This means that the majority of the schools’ population is not benefiting from these opportunities. Instead, they are settling for lower-level courses that are not pushing them to the best of their abilities.

It is unfortunate that so many of our community’s young people are missing out on being academically challenged in ways that could ultimately change their lives. This all too familiar issue is a complex community problem with no simple solutions. However it is one that should be addressed with the appropriate sense of urgency.

Robin Mwai is a Sophomore at LaFollette High School and serves as a staff writer for Dane County’s Teen Newspaper Simpson Street Free Press. Deidre Green is a LaFollette High School Graduate and is now a UW-Madison Senior. She is also a graduate of Simpson Street Free Press and now serves as Managing Editor.

Gifted in Math, and Poor

New York Times

To the Editor:

Re “Even Gifted Students Can’t Keep Up” (“Numbers Crunch” series, editorial, Dec. 15): Educators know that when the curriculum is set at an optimal difficulty level, students learn to persist, attend carefully and gain self-confidence. For mathematically gifted students, the curriculum must move more quickly and in greater depth so that they can become disciplined, resilient students.

When the mathematically gifted sons and daughters of affluent, well-educated parents are not challenged, their parents spend considerable amounts of time and money finding tutors, summer programs and online courses. As a psychologist who has worked for more than 20 years with the families of gifted students, I have seen how much time and money is required for this effort.

For mathematically gifted students from poorer families, there is neither the time nor the money to seek educational opportunities outside the public schools. A weak public school system without flexibility or adequate challenge can seriously limit the educational experiences and lifetime employment opportunities of these students. A weak public school system ultimately limits quality education to those few whose parents can pay for it privately.

JULIA B. OSBORN

Brooklyn, Dec. 19, 2013

Related: “They’re all rich, white kids and they’ll do just fine — NOT!”

Poverty influences children’s early brain development

University of Wisconsin-Madison News

Poverty may have direct implications for important, early steps in the development of the brain, saddling children of low-income families with slower rates of growth in two key brain structures, according to researchers from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

By age 4, children in families living with incomes under 200 percent of the federal poverty line have less gray matter — brain tissue critical for processing of information and execution of actions — than kids growing up in families with higher incomes.

“This is an important link between poverty and biology. We’re watching how poverty gets under the skin,” says Barbara Wolfe, professor of economics, population health sciences and public affairs and one of the authors of the study, published today in the journal PLOS ONE.

The differences among children of the poor became apparent through analysis of hundreds of brain scans from children beginning soon after birth and repeated every few months until 4 years of age. Children in poor families lagged behind in the development of the parietal and frontal regions of the brain — deficits that help explain behavioral, learning and attention problems more common among disadvantaged children.

The parietal lobe works as the network hub of the brain, connecting disparate parts to make use of stored or incoming information. The frontal lobe, according to UW-Madison psychology professor Seth Pollak, is one of the last parts of the brain to develop.

“It’s the executive. It’s the part of the brain we use to control our attention and regulate our behavior,” Pollak says. “Those are difficulties children have when transitioning to kindergarten, when educational disparities begin: Are you able to pay attention? Can you avoid a tantrum and stay in your seat? Can you make yourself work on a project?”

The maturation gap of children in poor families is more startling for the lack of difference at birth among the children studied.

“One of the things that is important here is that the infants’ brains look very similar at birth,” says Pollak, whose work is funded by the National Institutes of Health. “You start seeing the separation in brain growth between the children living in poverty and the more affluent children increase over time, which really implicates the postnatal environment.”

“I Came to Duke with an Empty Wallet”

KellyNoel Waldorf

The Chronicle

In my four years at Duke, I have tried to write this article many times. But I was afraid. I was afraid to reveal an integral part of myself. I’m poor.

Why is it not OK for me to talk about such an important part of my identity on Duke’s campus? Why is the word “poor” associated with words like lazy, unmotivated and uneducated? I am none of those things.

When was the first time I felt uncomfortable at Duke because of money? My second day of o-week. My FAC group wanted to meet at Mad Hatter’s Bakery; I went with them and said that I had already eaten on campus because I didn’t have cash to spend. Since then, I have continued to notice the presence of overt and subtle class issues and classism on campus. I couldn’t find a place for my “poor identity.” While writing my resume, I put McDonald’s under work experience. A friend leaned over and said, “Do you think it’s a good idea to put that on your resume?” In their eyes, it was better to list no work experience than to list this “lowly” position. I did not understand these mentalities and perceptions of my peers. Yet no one was talking about this discrepancy, this apparent class stratification that I was seeing all around me.

People associate many things with their identity: I’m a woman, I’m queer, I’m a poet. One of the most defining aspects of my identity is being poor. The amount of money (or lack thereof) in my bank account defines almost every decision I make, in a way that being a woman or being queer never has and never will. Not that these are not important as well, just that in my personal experience, they have been less defining. Money influenced the way I grew up and my family dynamics. It continues to influence the schools I choose to go to, the food I eat, the items I buy and the things I say and do.

I live in a reality where:

Sometimes I lie that I am busy when actually I just don’t have the money to eat out.

I don’t get to see my dad anymore because he moved several states away to try and find a better job to make ends meet.

I avoid going to Student Health because Duke insurance won’t do much if there is actually anything wrong with me.

Coming out as queer took a weekend and a few phone calls, but coming out as poor is still a daily challenge.

Getting my wisdom teeth removed at $400 per tooth is more of a funny joke than a possible reality.

I have been nearly 100 percent economically independent from my family since I left for college.

Textbook costs are impossible. Praise Perkins Library where all the books are free.

My mother has called me crying, telling me she doesn’t have the gas money to pick me up for Thanksgiving.

My humorously cynical, self-deprecating jokes about being homeless after graduation are mostly funny but also kind of a little bit true.

I am scared that the more I increase my “social mobility,” the further I will separate myself from my family.

Finances are always in the back (if not the forefront) of my mind, and I am always counting and re-counting to determine how I can manage my budget to pay for bills and living expenses.

This article is not meant to be a complaint about my life. This is not a sob story. There are good and bad things in my life, and we all face challenges. But it should be OK for me to talk about this aspect of my identity. Why has our culture made me so afraid or ashamed or embarrassed that I felt like I couldn’t tell my best friends “Hey, I just can’t afford to go out tonight”? I have always been afraid to discuss this with people, because they always seem to react with judgment or pity, and I want absolutely nothing to do with either of those. Sharing these realities could open a door to support, encouragement or simply openness.

Because I also live in a reality where:

I am proud of a job well done.

I feel a great sense of accomplishment when I get each paycheck.

I feel a bond of solidarity with those who are well acquainted with the food group “ramen.”

I would never trade my happy family memories for a stable bank account.

I would never trade my perspective or work ethic or appreciation of life for money.

Most times it certainly would be nice to have more financial stability, but I love the person I have become for the background I have had.

It is time to start acknowledging class at Duke. Duke is great because of its amazing financial aid packages. My ability to go here is truly incredible. Duke is not great because so many of the students fundamentally do not understand the necessity for a discussion of class identity and classism. Duke needs to look past its blind spot and start discussing class stratification on campus to create a more welcoming environment for poor students.

If you have ever felt like this important piece of your identity was not welcome at Duke, know that you are not the only one. I want you to know that “poor” is not a dirty word. It is OK to talk about your experiences and your identity in relation to socioeconomic status. It is OK to tell the truth and be yourself. Stop worrying whether it will make other people feel uncomfortable. People can learn a lot about themselves from the things that make them uncomfortable. I want to say to you that no matter what socioeconomic status you come from, your experiences are worthy.

And because no one in four years has said it yet to me: It’s okay to be poor and go to Duke.

The Oklahoma Model for American Pre-K

Nicholas Kristof

As readers know, one of my hobby horses is the need for early childhood education as the most cost-effective way to break the cycles of poverty in America. But the issue never gets much traction, and one reason is the perception that it’s politically hopeless: Republicans would never go for such a program. My Sunday column tries to push back at the assumption that it’s hopeless and notes that one of the leaders in providing pre-K in America is-not Massachusetts, not New York, not some other blue state, but reliably red Oklahoma. It’s all the more surprising because Oklahoma spends less per pupil on education than almost any other state, and pays its teachers near the bottom. This is not a state that believes in lavish spending on schooling. Yet, quite remarkably, it provides universal high-quality pre-K, with a ratio of no more than 10 students per staff member, and all teachers have a college degree.

My own take is that even earlier interventions may get even more bang for the buck than pre-K for 4-year-olds, and sure enough Oklahoma also invests in those, including home visitation programs to coach parents on reading to toddlers and talking more to them. It also has some programs for kids 0 to 3 if they’re from disadvantaged families. These are no silver bullet to defeat poverty-there isn’t one-but there seems a recognition in Oklahoma that they work in improving school performance and life outcomes and reduce the risk that poverty will be transmitted from generation to generation. So if Oklahoma can do it, why not the rest of the country?

Bipartisan legislation is expected to be introduced this coming week in Congress to establish national support for pre-K programs, and polling shows the idea has broad support. It’ll be an uphill struggle, but I’m hoping that Congress will, like Oklahoma, see that this isn’t a social welfare program exactly, but an investment in our children and our future. Read the column and help spread the word about the need for this legislation!

The column: “Oklahoma! Where the Kids Learn Early”

“The aim is to break the cycle of poverty, which is about so much more than a lack of money.”

Childhood Poverty Linked to Poor Brain Development

Caroline Cassels

Exposure to poverty in early childhood negatively affects brain development, but good-quality caregiving may help offset this effect, new research suggests. A longitudinal imaging study shows that young children exposed to poverty have smaller white and cortical gray matter as well as hippocampal and amygdala volumes, as measured during school age and early adolescence.