With affirmative action under attack and economic mobility feared to be stagnating, top colleges profess a growing commitment to recruiting poor students. But a comparison of low-income enrollment shows wide disparities among the most competitive private colleges. A student at Vassar, for example, is three times as likely to receive a need-based Pell Grant as one at Washington University in St. Louis.

“It’s a question of how serious you are about it,” said Catharine Bond Hill, the president of Vassar. She said of colleges with multibillion-dollar endowments and numerous tax exemptions that recruit few poor students, “Shame on you.”

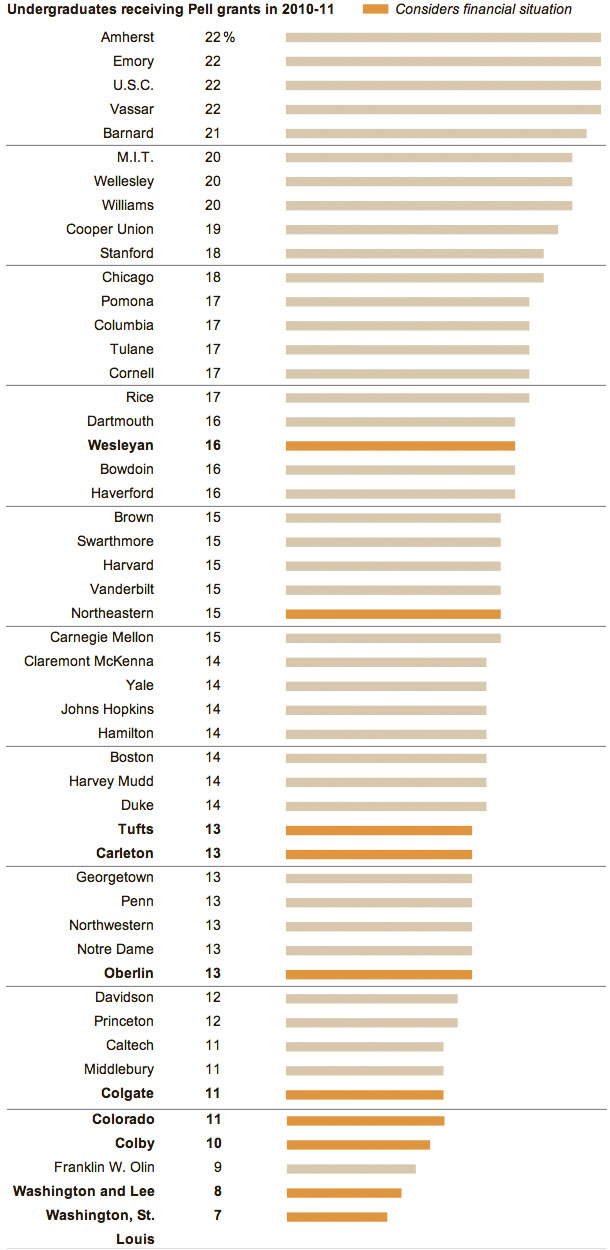

At Vassar, Amherst College and Emory University, 22 percent of undergraduates in 2010-11 received federal Pell Grants, which go mostly to students whose families earn less than $30,000 a year. The same year, the most recent in the federal Department of Education database, only 7 percent of undergraduates at Washington University were Pell recipients, and 8 percent at Washington and Lee University were, according to research by The New York Times.

Researchers at Georgetown University have found that at the most competitive colleges, only 14 percent of students come from the lower 50 percent of families by income. That figure has not increased over more than two decades, an indication that a generation of pledges to diversify has not amounted to much. Top colleges differ markedly in how aggressively they hunt for qualified teenagers from poorer families, how they assess applicants who need aid, and how they distribute the available aid dollars.

Some institutions argue that they do not have the resources to be as generous as the top colleges, and for most colleges, with meager endowments, that is no doubt true. But among the elites, nearly all of them with large endowments, there is little correlation between a university’s wealth and the number of students who receive Pell Grants, which did not exceed $5,550 per student last year.

Related:Travis Reginal and Justin Porter were friends back in Jackson, Miss. They attended William B. Murrah High School, which is 97 percent African-American and 67 percent low income. Murrah is no Ivy feeder. Low-income students rarely apply to the nation’s best colleges. But Mr. Reginal just completed a first year at Yale, Mr. Porter at Harvard. Below, they write about their respective journeys.

Reflections on the Road to Yale: A First-Generation Student Striving to Inspire Black Youth by Travis Reginal:

For low-income African-American youth, the issue is rooted in low expectations. There appear to be two extremes: just getting by or being the rare gifted student. Most don’t know what success looks like. Being at Yale has raised my awareness of the soft bigotry of elementary and high school teachers and administrators who expect no progress in their students. At Yale, the quality of your work must increase over the course of the term or your grade will decrease. It propelled me to work harder.

Reflections on the Road to Harvard: A Classic High Achiever, Minus the Money for a College Consultant by Justin Porter

I do not believe that increasing financial aid packages and creating glossy brochures alone will reverse this trend. The true forces that are keeping us away from elite colleges are cultural: the fear of entering an alien environment, the guilt of leaving loved ones alone to deal with increasing economic pressure, the impulse to work to support oneself and one’s family. I found myself distracted even while doing problem sets, questioning my role at this weird place. I began to think, “Who am I, anyway, to think I belong at Harvard, the alma mater of the Bushes, the Kennedys and the Romneys? Maybe I should have stayed in Mississippi where I belonged.”