The New Teacher Project’s (TNTP) recent report on teacher retention, called “The Irreplaceables,” garnered quite a bit of media attention. In a discussion of this report, I argued, among other things, that the label “irreplaceable” is a highly exaggerated way of describing their definitions, which, by the way, varied between the five districts included in the analysis. In general, TNTP’s definitions are better-described as “probably above average in at least one subject” (and this distinction matters for how one interprets the results).

I’d like to elaborate a bit on this issue – that is, how to categorize teachers’ growth model estimates, which one might do, for example, when incorporating them into a final evaluation score. This choice, which receives virtually no discussion in TNTP’s report, is always a judgment call to some degree, but it’s an important one for accountability policies. Many states and districts are drawing those very lines between teachers (and schools), and attaching consequences and rewards to the outcomes.

Let’s take a very quick look, using the publicly-released 2010 “teacher data reports” from New York City (there are details about the data in the first footnote*). Keep in mind that these are just value-added estimates, and are thus, at best, incomplete measures of the performance of teachers (however, importantly, the discussion below is not specific to growth models; it can apply to many different types of performance measures).

Are Sleepy Students Learning?

How does the mind work–and especially how does it learn? Teachers’ instructional decisions are based on a mix of theories learned in teacher education, trial and error, craft knowledge, and gut instinct. Such knowledge often serves us well, but is there anything sturdier to rely on?

Cognitive science is an interdisciplinary field of researchers from psychology, neuroscience, linguistics, philosophy, computer science, and anthropology who seek to understand the mind. In this regular American Educator column, we consider findings from this field that are strong and clear enough to merit class- room application.

Question: Some of my students seem really sleepy–they stifle yawns and struggle to keep tired eyes open–especially in the morning. This can’t be good for their learning, right? Is there any- thing I can do to help these students?

Answer: Sleep is indeed essential to learning, and US teenag- ers (and teenagers in most industrialized countries) don’t get enough. Although recent work shows there is a strong biological reason that teens tend not to sleep enough, there is some good news in this research. First, the impact on learning, although quite real, does not appear to be as drastic as we might fear. Second, the sleep deficit teens tend to run is not inevitable; with some plan- ning, they can get more shuteye.

Keep it in the family Home schooling: is growing ever faster

Every morning five-year-old Tristan starts his school day by reading in bed with his mother. He especially likes Enid Blyton. And even though he often doesn’t bother to get out of his pyjamas in time for his first class of the day, at the age of five he has a reading age of between seven and eight. He is also ahead of his peers in a variety of subjects–all, his mother reckons, thanks to home schooling.

Three decades ago home schooling was illegal in 30 states. It was considered a fringe phenomenon, pursued by cranks, and parents who tried it were often persecuted and sometimes jailed. Today it is legal everywhere, and is probably the fastest-growing form of education in America. According to a new book, “Home Schooling in America”, by Joseph Murphy, a professor at Vanderbilt University, in 1975 10,000-15,000 children were taught at home. Today around 2m are–about the same number as attend charter schools.

We can strengthen public schools by providing all kids the opportunities they need to learn

We live in an era in which the perceptions of public education have been formed based upon political ideologues bent on reform by means of accountability measures. These accountability measures in large part tie both school and teacher performance to high-stakes standardized tests. While it is reasonable that there be expectations established for teacher performance, it is not OK to impose punitive measures upon those performing in the most challenging environments with variables that extend beyond the classroom which impact learning.

Recently, a non-partisan think tank, the Forward Institute, released their findings in a study examining school achievement and poverty in public and charter schools. A key finding is that poverty is closely linked to academic achievement, as measured by high-stakes standardized testing, in the state of Wisconsin.

According to the statistical analysis, charter schools, long lauded as the solution to the ills of the public school system, actually fare worse in addressing the needs of our most disadvantaged populations. Statewide, public school students from low socioeconomic backgrounds actually outperform their peers in charter school settings. This study places public education within the context of the 2011-2013 Wisconsin biennial budget (Act 32).

‘What are you looking at?’ and other college application questions

Stanford University: Write a note to your future roommate that reveals something about you or that will help your roommate — and us — know you better.

Carleton College: Have you ever tossed around a Frisbee___, a hot potato___, an idea___?

Connecticut College: Tell us about your favorite place and why it holds special meaning for you. It can be close to home or on another continent, your kitchen or a mountaintop.

Pomona College: You are walking down the street when something catches your eye. You stop and stare for a long while, amazed and fascinated. What are you looking at?

A Modest Proposal on State Standards

A few years ago while serving as a VP at the Goldwater Institute I received a request to come out hard against the adoption of Common Core standards in Arizona. I didn’t know whether it would have mattered or not but the request originated from people who I continue now to hold in a great deal of respect. I considered the matter very carefully. I had deep misgivings regarding Common Core at the time, the most serious of which was the governance of the standards over time. At the time I was of the opinion that unless Ben Bernanke took up the task of governing the standards that it would inevitably follow that Common Core would eventually result in the Great American Dummy Down.

Nevertheless in the end I decided not to oppose Arizona’s adoption of Common Core standards. Regardless of how bad Common Core started out or later became, Arizona simply had nothing to lose. Arizona had just about every testing problem you could imagine- dummied down cut scores, massive teaching to test items, and something at least in the direct vicinity of outright fraud by state officials regarding the state’s testing system. Our state scores had “improved” substantially through a combination of lowered cut scores and teaching to the test items, but NAEP showed Arizona scoring below the national average on every single test and precious little progress. The status quo was worse than a waste of time.

A Game-Changer for Global Education

Recently at the Brookings Center for Universal Education (CUE), we were joined by colleagues from around the world in a two-day conference to discuss the status of global education and strategies for future action. Activities during the two-day conference included: a public event with United Nations Special Envoy for Global Education Gordon Brown and Director of the White House National Economic Council Gene Sperling; a private meeting with a delegation from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; a meeting convened by Women Thrive Worldwide; a private all-day research symposium on ‘Learning in the Developing World’; and presentations by CUE’s Global Guest scholars.

The central theme of the events was to understand the new opportunities that Education First, the U.N. secretary-general’s new five-year global education initiative, affords our community. There was broad agreement that this new initiative has the potential to be a game-changer in global education if it succeeds in its mission to, in the words of Carol Bellamy, get existing and new actors alike to “do more and do better.” Not only does Education First inject much needed leadership and energy into global education advocacy and provide a bold vision for the future, but it also puts forward a set of concrete steps for actors to take if they want to lend their hands to the effort.

A Guide for the Perplexed — A Review of Rigorous Charter Research

So you say charter schools don’t work. That’s an empirical claim. It needs to be backed up by evidence. Here’s a helpful guide to the most rigorous research available. Once you’ve tackled this material, you’ll be in position to prove your point.

As you probably know, the gold standard method of research in social science is called random assignment. Charter schools are particularly well-suited for random assignment evaluations, since they’re usually required by law to admit students by lottery. The lotteries are fair to families – that’s why they’re put in place. But they also allow researchers to make fair comparisons between students who win or lose lotteries to attend charter schools.

To date, nine studies lottery-based evaluations of charter schools have been released. Let’s go through them, starting with the earliest work.

The first random assignment study of charter schools was released in 2004 by Caroline Hoxby and Jonah Rockoff. It focused on Chicago International Charter School. After three years, charter students had significantly higher reading scores, equal to 3.3 to 4.2 points on 100-point rankings. Gains were even stronger for younger students.

Program teaches healthy habits for young and old

Jane Qualle found a nice fit with the CATCH Healthy Habits program when she looked for volunteer opportunities after she retired as a nurse.

CATCH Healthy Habits in Madison pairs adults 50 and older with children at various sites to encourage healthier eating and physical activity. It also is aimed at helping the adults, who can learn alongside the children and receive benefits by volunteering. CATCH stands for Coordinated Approach To Child Health.

After first volunteering at a site farther away from her home, Qualle volunteered at the Mendota Elementary School site, which was about a mile from home.

She usually walks, which allows her to get some exercise and serve as a role model for the children.

“I’m just a believer — the more active you are, the healthier you are,” Qualle said. “It’s an opportunity for kids to actually play rather than sitting in front of the TV or computer.”

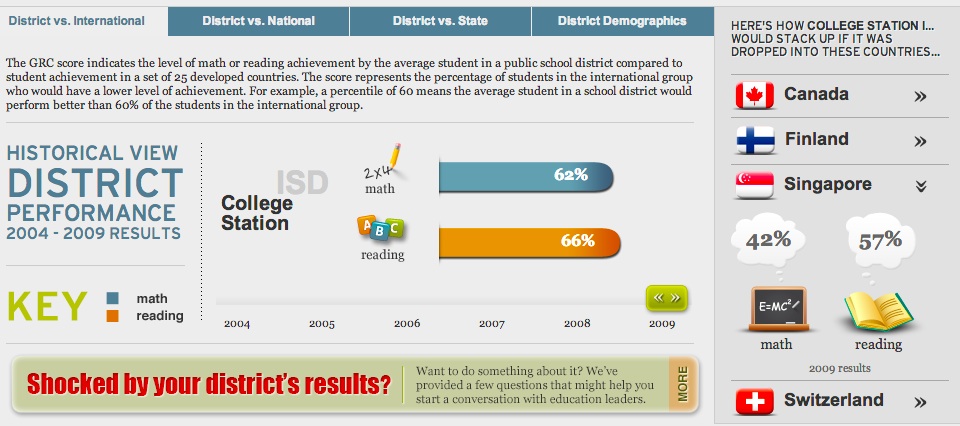

No more Flori-duh. State’s fourth-grade readers go from bottom of the nation to top of the world

Mike Thomas, via a kind reader’s email:

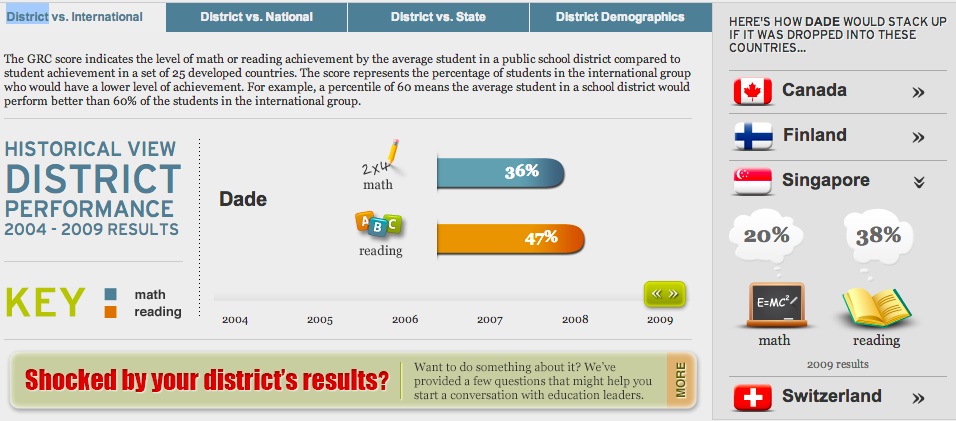

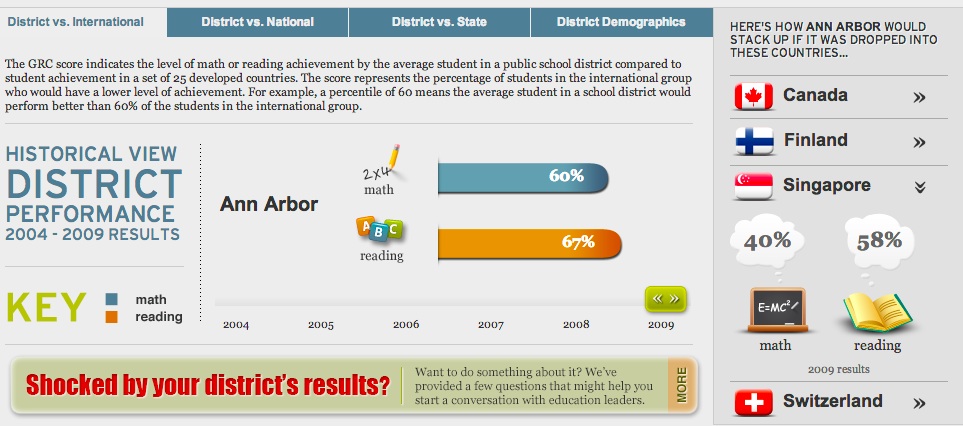

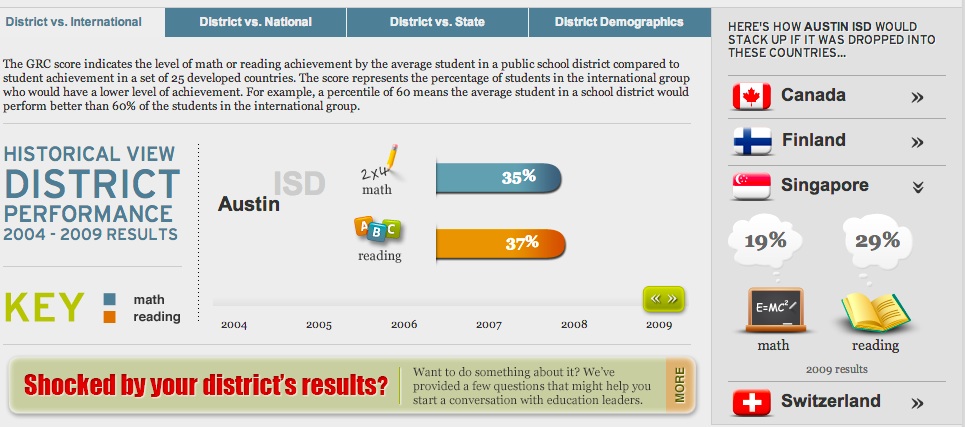

Kids in Singapore and Finland have long distinguished themselves on international academic tests, leaving American kids far, far, far behind.

They would rule the 21st Century while our kids would assemble snow globes, sew sneakers, man the call centers and figure out how to pay their parents’ entitlements on 93 cents a day.

If things weren’t bad enough, now we have the results of international fourth grade reading assessments. And not only were the usual suspects at the top of the list, we have a new nation to rub its superiority in our face, a nation that bested even Singapore and Finland.

The kids there not only significantly outperformed American kids, they had almost triple the percent of students reading at an advanced level when compared to the international average.

The PIRLS results are better than you may realize.

Last week, the results of the 2011 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) were published. This test compared reading ability in 4th grade children.

U.S. fourth-graders ranked 6th among 45 participating countries. Even better, US kids scored significantly better than the last time the test was administered in 2006.

There’s a small but decisive factor that is often forgotten in these discussions: differences in orthography across languages.

Lots of factors go into learning to read. The most obvious is learning to decode–learning the relationship between letters and (in most languages) sounds. Decode is an apt term. The correspondence of letters and sound is a code that must be cracked.

In some languages the correspondence is relatively straightforward, meaning that a given letter or combination of letters reliably corresponds to a given sound. Such languages are said to have a shallow orthography. Examples include Finnish, Italian, and Spanish.

In other languages, the correspondence is less consistent. English is one such language. Consider the letter sequence “ough.” How should that be pronounced? It depends on whether it’s part of the word “cough,” “through,” “although,” or “plough.” In these languages, there are more multi-letter sound units, more context-depenent rules and more out and out quirks.

Colleges Pay to Protect Students from Toxic Google Results (!)

Most college students understand that it’s probably a good idea to remove online photos of themselves drinking beer or mooning the camera as they plot their entry into the professional world.

But few realize they should spend just as much time highlighting the good news about themselves on the web.

Now some college career-services centers are providing tools to help their students influence the results a recruiter might see when typing their names into a search engine.

Schools, ever more conscious of their job-placement figures, are moving a step beyond simply warning students to clean up their profiles. They are encouraging students to put forward information that can help them land jobs – and investing in services to help them do so.

Higher education: our MP3 is the mooc Academics have watched the internet change the music industry, books and news. And yet, now it’s happening in higher education, we are about to screw it up

Fifteen years ago, a research group called The Fraunhofer Institute announced a new digital format for compressing movie files. This wasn’t a terribly momentous invention, but it did have one interesting side-effect: Fraunhofer also had to figure out how to compress the soundtrack. The result was the Motion Picture Experts Group Format 1, Audio Layer III, a format you know and love, though only by its acronym, MP3.

The recording industry concluded this new format would be no threat, because quality mattered most. Who would listen to an MP3 when they could buy a better-sounding CD? Then Napster launched, and quickly became the fastest-growing piece of software in history. The industry sued Napster and won, and it collapsed even more suddenly than it had arisen.

If Napster had only been about free access, control of legal distribution of music would then have returned the record labels. That’s not what happened. Instead, Spotify happened. ITunes happened. Amazon began selling songs in the hated MP3 format.

How did the recording industry win the battle but lose the war? They crushed Napster, but what they couldn’t kill was the story Napster told.

The Future of Academic Impact

LSE’s public policy group put on an excellent conference programme on 4 December at Beveridge Hall. The conference explored the themes:1) the Economic impact of academic research; 2) impact and the new digital paradigm; 3) next steps in assessing impact; 4) impact as a driver for Open Access. Throughout the day there were break-out sessions on different types of social media for enhancing academic impact but sadly I was unable to attend those (for more info see here).

Upon arrival on a cold London morning, I was struck by the size of the pastries on offer but once I had assured myself of one I bustled into the main hall for the beginning of the day’s sessions. The economic impact of academic research was a striking title, and I was unsure how the pounds were going to be counted. Patrick Dunleavy set out the work he had been doing on the impact of social sciences and the artificial lines in the sand he had to draw to demarcate the social sciences from other work in an increasingly interdisciplinary world. This included impressive figures such as £4.8bn annually as the total value-added from social sciences to the economy.

School Takes New Tack on Work Study

“I was raised into believing that money is everything,” said Maire Mendoza, 19, crying at her own tale.

Her parents are near-invisibles in this city that they’ve heard called a city of dreams. They left Mexico before Maire was born and have toiled anonymously ever since — her mother a baby sitter these days, her father a restaurant worker.

They raised their girls as pragmatic survivors. So it was startling when Maire came to them not long ago with an epiphany: “I now know that I don’t want to work for money,” she said, to bafflement. But her father, sensing his limitations, deferred. “You’re probably right,” she remembers him saying, “and it’s because you go to school and you know things that we don’t know.”

Maryland Unveils new school accountability system

The State Department of Education on Monday unveiled a new way of assessing accountability of each school, a measure called the School Progress Index (SPI) that school officials say will cut in half the percentage of non-proficient students by 2017.

The Maryland State Department of Education unveiled Monday a new way of assessing accountability of each school in Maryland under the waiver that it received from the federal No Child Left Behind act.

The new measure, the School Progress Index, aims to cut in half the percentage of students who do not score at a proficient level on the state’s assessments by 2017, school officials said. It replaces the system of measuring school targets called adequate yearly progress.

K-12 Tax & Spending Climate: How Big Deficits Became the Norm?

Big budget deficits haven’t always been with us.

From the end of the Eisenhower years through the Carter presidency, the deficit averaged a modest 1.4% of the nation’s economic output. The budget was nearly balanced in seven of the 20 years from 1960 to 1979. And, as Bill Clinton reminds at every opportunity, the U.S. government was in surplus for four years at the end of his presidency.

In January 2001, the Congressional Budget Office projected annual surpluses totaling $5.6 trillion over the following 10 years. Alan Greenspan, the Federal Reserve chairman at the time, worried out loud about the consequences of paying off the federal debt, such as the possibility that the government might invest its surpluses in corporate stock and meddle in management.

New Jersey Teacher Tenure: Last in First Out

From NJ Ed. Comm. Chris Cerf’s just-released Education Funding Report:

It is the Department’s hope that in considering changes to the SFRA funding formula, the Legislature will also address some of the Education Funding Report’s recommendations. Three in particular are worth highlighting. First, notwithstanding the change to the State’s tenure law, where budget or other constraints require school districts to lay off teachers, state law forces them to do so based on seniority, not classroom effectiveness. The result is a system that prizes longevity over student outcomes. Such a system is tragically unfair to disadvantaged children and cannot be permitted to continue.

The other two recommendations Cerf refers to are creating incentives for school reform (“In fact, historically, the worse a school district was performing, the more state aid it received”) and phasing out “adjustment aid,” which was intended to protect districts as the state transitioned from the old funding formula (Abbott-driven) to the new one, the School Funding Reform Act (SFRA). From Cerf’s report:

$1.2 million Madison schools foundation grant targets achievement gap

Two yet-to-be-determined Madison elementary schools will split a $1.2 million grant to accelerate low-income and minority student achievement, the Foundation for Madison’s Public Schools announced Wednesday.

School Board member Mary Burke contributed the funding for the grant, which will be awarded in $200,000 installments over three years.

The foundation currently distributes about $400,000 a year to Madison schools, so the grant will double that amount, foundation executive director Stephanie Hayden said. The goal of the grant is to demonstrate that closing the achievement gap can be done more quickly than currently expected.

“We would hope that others in the community would step forward and fund similar things,” Hayden said. “We really view these as a demonstration project to show it can be done.”

The eligible non-charter schools must have at least 50 percent of students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. Eighteen elementary schools meet that threshold this year.

Are Residents Losing Their Edge in Public University Admissions? The Case at the University of Washington

Grant Blume, Marguerite Roza via a kind Deb Britt email

There is a longstanding implicit bargain that comes with state-supported higher education: subsidized prices for in-state students, and resident preference in the admissions process.

News reports now suggest that public universities across the country are shifting more spots to nonresidents (who pay higher tuitions) in order to plug budget gaps, prompting critics to worry that residents are losing their advantage in the admissions process.

Do residents still have an advantage, or are admissions standards leveling for the two groups? Or, are admissions actually now favoring out-of-state applicants?

This case study examines admissions data at the University of Washington in order to quantify the effect on admissions standards for residents versus nonresidents. Like many other state flagship universities, the UW has suffered from constrained state revenues during the recent recessionary years. The findings suggest that Washington residents have indeed lost their edge in UW admissions, and in fact may have been at a disadvantage in 2011.

Madison Teachers Newsletter: Teacher Retirement and TERP Deadline February 15

Madison Teaches, Inc. Solidarity Newsletter via a kind Linda Doeseckle email:

In order for one to be eligible for the MTI-negotiated Teacher Emeritus Retirement Program (TERP) [Clusty Search], he/she must be a full-time teacher, at least 55 years old, with a combined age (as of August 30 in one’s retirement year) and years of service in the District totaling at least 75. (For example, a teacher who is 57 and has eighteen (18) years of service to the MMSD would be eligible: 57 + 18 = 75.) Teachers who are younger than age 55 are eligible if they have worked for the MMSD at least 30 years. Up to ten (10) part-time teachers may participate in TERP each year provided they have worked full-time within the last ten (10) years and meet the eligibility criteria described above.

Retirement notifications, including completed TERP agreements, are due in the District’s Department of Human Resources no later than February 15. Appointments can be made to complete the TERP agreement and discuss insurance options at retirement by calling the District’s Benefits Manager, Sharon Hennessy at 663-1795.

MTI was successful in negotiations for the 2009-13 and 2013-14 Contracts in negotiating a guaranteed continuance of TERP. Thus, MTI members can be assured that TERP runs through 2014 and not feel pressured into retirement before they are ready.

MTI Assistant Director Doug Keillor is available to provide guidance and/or to provide estimated benefits for TERP , insurance continuation, application of one’ s Retirement Insurance Account, WRS and Social Security. Call MTI Headquarters (257-0491) to schedule an appointment.

Rising Inequality, Even Among College Presidents

Eye-popping tales of growing income inequality are hardly new. By now, nearly every American must be painfully aware of the widening pay gap between top executives and shop floor laborers; between “Master of the Universe” financiers and pretty much everyone else.

But here’s what may not be as familiar: Widening income disparities are hardly limited to the commercial world, and even among very successful individuals performing similar tasks, income differences have grown.

Recently, thanks to data compiled by The Chronicle of Higher Education, I saw these macro trends reduced to the micro level in a perhaps unlikely setting: institutions of higher learning.

Much more on Steven Rattner.

The End of Unions? What Michigan Governor Rick Snyder gets right and wrong about labor policy

The age of big government is now upon us. The question is how to respond to this daunting reality. One possible approach is prudential acquiescence to the inevitable. Conservatives could work toward incremental reform within today’s political paradigm. The Hoover Institution’s own Peter Berkowitz offers this advice in his thoughtful column in the Wall Street Journal. Libertarians, in particular, must “absorb” the lesson that frontal assaults on New Deal-era policies are out. He writes:

[C]onservatives must redouble their efforts to reform sloppy and incompetent government and resist government’s inherent expansionist tendencies and progressivism’s reflexive leveling proclivities. But to undertake to dismantle or even substantially roll back the welfare and regulatory state reflects a distinctly unconservative refusal to ground political goals in political realities.

Conservatives can and should focus on restraining spending, reducing regulation, reforming the tax code, and generally reining in our sprawling federal government. But conservatives should retire misleading talk of small government. Instead, they should think and speak in terms of limited government.I fear the downside of Berkowitz’s counsel of moderation. For starters, no one can police Berkowitz’s elusive line between “small” and “limited” government. At its core, Berkowitz’s wise counsel exposes the Achilles heel of all conservative thought, which can be found in the writings of such notables as David Brooks and the late Russell Kirk. Their desire to “conserve” the best of the status quo offers no normative explanation of which institutions and practices are worthy of intellectual respect and which are not. No one doubts that politics depends on the art of compromise. But compromise only works for politicians who know where they want to go and how to get there.

2012-13 Sun Prairie School District Administrator Increases and Pay

It seems only fair that if the teacher salaries were published, then we also publish the salaries for administrators.

We’ve got 10 members of the $100K club plus one that’s right on the edge.

The question in our minds right now is that a 2% pool was set aside for administrators, admin support, and Local 60. The average increases was 2% for these groups.

Montgomery superintendent shows courage in denouncing standardized tests

For more than a decade, school standardized tests have been the magic keys that were supposed to unlock the door to a promised realm of American students able to read and do sums as well as their counterparts in Asia and Europe.

A generation of U.S. education reformers has assured us that if we would just rely mostly on test scores and other hard data to guide decisions, then all manner of good results would ensue. Foundations gave millions of dollars to encourage it. The Obama administration embraced the cause, lest it stand accused of short-changing kids.

It was always a fairy tale. Tests are necessary, of course, but the mania for them has become self-defeating. They don’t account for the vast differences in children’s social, economic and family backgrounds. Good teachers give up on proven classroom techniques and instead “teach to the test.”

Now, finally, somebody with standing is getting attention for denouncing the madness.

The truth-teller is one of our own from the Washington region, Montgomery County Superintendent Joshua P. Starr. He has only been here for a year and a half, but he arrived with an impressive résumé and is emerging as a credible national voice urging a more reasoned and deliberate path to educational progress.

In Minn., new tactics to help immigrant students

Imagine trying to read and solve math problems in a school where you don’t speak the language of your teacher and classmates.

That’s the challenge facing roughly 65,000 students in Minnesota, or 8 percent of the student population, who are learning English as they go through the school.

Despite some recent improvement in their test scores, English learners, whose numbers are growing, perform far below the state average in reading, math and science. Only slightly more than half graduate from high school in four years. To boost English learners’ performance, some Minnesota schools are trying new approaches designed to help them more quickly grasp the language. Among them is Kennedy Elementary in Willmar, Minn., which has a growing number of students from Somalia.

School Board president James Howard faces challenger

Madison School Board president James Howard has drawn an opponent setting up the likelihood of three races for the spring election.

Greg Packnett, a Democratic legislative aide, has filed paperwork to run for Howard’s seat. Howard has yet to file, but tells me he plans to do so by the Jan. 2 deadline.

Dean Loumos, executive director of low-income housing provider Housing Initiatives, and Wayne Strong, a retiring Madison police lieutenant, have filed to run for the seat being vacated by Beth Moss.

Adam Kassulke, a former Milwaukee teacher whose daughter attends Shabazz High School, and Ananda Mirilli, restorative justice coordinator with YWCA Madison and a Nuestro Mundo parent, have filed to run for the seat being vacated by Maya Cole.

One other update: State Rep. Kelda Roys and disability rights attorney Jeff Spitzer-Resnick, who previously said they were thinking about running, have decided not to run.

A Guide for the Perplexed — A Review of Rigorous Charter Research

So you say charter schools don’t work. That’s an empirical claim. It needs to be backed up by evidence. Here’s a helpful guide to the most rigorous research available. Once you’ve tackled this material, you’ll be in position to prove your point.

As you probably know, the gold standard method of research in social science is called random assignment. Charter schools are particularly well-suited for random assignment evaluations, since they’re usually required by law to admit students by lottery. The lotteries are fair to families – that’s why they’re put in place. But they also allow researchers to make fair comparisons between students who win or lose lotteries to attend charter schools.

To date, nine studies lottery-based evaluations of charter schools have been released. Let’s go through them, starting with the earliest work.

The first random assignment study of charter schools was released in 2004 by Caroline Hoxby and Jonah Rockoff. It focused on Chicago International Charter School. After three years, charter students had significantly higher reading scores, equal to 3.3 to 4.2 points on 100-point rankings. Gains were even stronger for younger students.

Related: Madison Mayor Paul Soglin: “We are not interested in the development of new charter schools”.

Are MOOCs becoming mechanisms for international competition in global higher ed?

Are Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) becoming mechanisms for international competition in global higher education? Where are Europe’s MOOCs in the context of the dearth of lifelong learning opportunities in the region, or both the internal and external/global dimensions of the European Higher Education Area? Who will establish the first MOOCs platform that spans the Arabic-speaking world? Are the MOOCs born in the United States (circa 2012) poised to become post-national platforms of higher ed given their cosmopolitan multilingual architects? And will my birth country of Canada ever sort out a strategy regarding MOOCs (a point also made by George Siemens), or will Canada depend on US platforms like it does in many sectors and spheres of life, for good and bad.

I couldn’t help but think about some of these questions when England’s Open University (est. 1969) announced last Thursday that it was going to establish a MOOCs platform that will be known as Futurelearn. Link here for the press release and here for some media coverage of Futurelearn. In total 12 UK-based universities will initially be associated with the Futurelearn platform:

Students aren’t the only ones cheating–some professors are, too. Uri Simonsohn is out to bust them.

Uri Simonsohn, a research psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School, did not set out to be a vigilante. His first step down that path came two years ago, at a dinner with some fellow social psychologists in St. Louis. The pisco sours were flowing, Simonsohn recently told me, as the scholars began to indiscreetly name and shame various “crazy findings we didn’t believe.” Social psychology–the subfield of psychology devoted to how social interaction affects human thought and action–routinely produces all sorts of findings that are, if not crazy, strongly counterintuitive. For example, one body of research focuses on how small, subtle changes–say, in a person’s environment or positioning–can have surprisingly large effects on their behavior. Idiosyncratic social-psychology findings like these are often picked up by the press and on Freakonomics-style blogs. But the crowd at the restaurant wasn’t buying some of the field’s more recent studies. Their skepticism helped convince Simonsohn that something in social psychology had gone horribly awry. “When you have scientific evidence,” he told me, “and you put that against your intuition, and you have so little trust in the scientific evidence that you side with your gut–something is broken.”

Simonsohn does not look like a vigilante–or, for that matter, like a business-school professor: at 37, in his jeans, T-shirt, and Keen-style water sandals, he might be mistaken for a grad student. And yet he is anything but laid-back. He is, on the contrary, seized by the conviction that science is beset by sloppy statistical maneuvering and, in some cases, outright fraud. He has therefore been moonlighting as a fraud-buster, developing techniques to help detect doctored data in other people’s research. Already, in the space of less than a year, he has blown up two colleagues’ careers. (In a third instance, he feels sure fraud occurred, but he hasn’t yet nailed down the case.) In so doing, he hopes to keep social psychology from falling into disrepute.

Simonsohn initially targeted not flagrant dishonesty, but loose methodology. In a paper called “False-Positive Psychology,” published in the prestigious journal Psychological Science, he and two colleagues–Leif Nelson, a professor at the University of California at Berkeley, and Wharton’s Joseph Simmons–showed that psychologists could all but guarantee an interesting research finding if they were creative enough with their statistics and procedures.

What is the Role of the Teacher in 21st Century Education?

I am a member of many professional learning communities. I do a tremendous amount of reading, trying to be at the cutting edge of knowledge in my field: education. Here’s what I mean when I say “cutting edge”: to be one of the first people to know about new developments and news in the field of education in general, and English Language Teaching, specifically, which is my field in which I work, as an educator in an International Baccalaureate World School, located in Santiago, Chile.

Well, as I said, while reading I just came across an open question, asked by a colleague from Bengaluru, India, named Shivananda Salgame.

No, I didn’t make up that name, nor the question. Trust me, both the person and the question are real. In fact, let me first introduce you to Shivananda a bit, and then I’ll add my reflections to the question he posed.

If You Build It, Debt Will Come

When we read or hear stories in the news media these days about debt in higher education, we typically assume they are about the trillion dollars in student loans held by college graduates and their families.

But last week The New York Times put the spotlight on an often ignored angle to questions of debt in higher education: the amount of money owed by colleges and universities themselves.

“The pile of debt — $205 billion outstanding in 2011 at the colleges rated by Moody’s — comes at a time of increasing uncertainty in academia,” Andrew Martin of The Times wrote in a front-page story.

In some ways, the news is even worse. The Times only counted debt that is tracked by Moody’s, one of the big-three credit-rating agencies. Moody’s only rates the debt at a few hundred of the nation’s colleges, usually the ones that are in solid financial shape. Data from the Education Department paints a picture of more red ink for all of higher education: $277 billion, double what colleges held in debt in 2000.

Who Can Still Afford State U ?

Though Colorado taxpayers now provide more funding in absolute terms, those funds cover a much smaller share of CU’s total spending, which has grown enormously. In 1985, when Mr. Joiner was a freshman, state appropriations paid 37% of the Boulder campus’s $115 million “general fund” budget. In the current academic year, the state is picking up 9% of a budget that has grown to $600 million.

A number of factors have helped to fuel the soaring cost of public colleges. Administrative costs have soared nationwide, and many administrators have secured big pay increases–including some at CU, in 2011. Teaching loads have declined for tenured faculty at many schools, adding to costs. Between 2001 and 2011, the Department of Education says, the number of managers at U.S. colleges and universities grew 50% faster than the number of instructors. What’s more, schools have spent liberally on fancier dorms, dining halls and gyms to compete for students.

Still, Colorado ranks 48th among states in per-person spending on higher education, down from sixth in 1970, says Brian Burnett, a vice chancellor at the University of Colorado’s Colorado Springs campus who recently published his Ph.D. dissertation on Colorado’s higher-education funding.

Lawrence schools planning expanded career and technical education

The Lawrence school board hopes to finalize plans for an upcoming bond election, including plans for expanding career and technical education programs, when the board holds a special meeting this week.

The board meets at 7 p.m. Monday at the district office, 110 McDonald Drive.

Rick Henry, career and technical education specialist for the district, updated the board last week about the kinds of career and technical programs that officials would like to offer by forming partnerships with area community and technical colleges to teach classes at a facility in Lawrence.

Those programs include health sciences, machine technology, computer networking and commercial construction. Those would be in addition to the culinary arts program currently offered at the facility. Officials estimated the cost of launching those programs at about $4.4 million.

The Lawrence School District plans to spend $173,879,557 during 2012-2013 for 11,000 students or $15,807/student. PRK-12 Madison school district per student spending is $14,242 during 2012-2013.

K-12 Tax & Spending Climate: States that Spend Less, Tax Less – and Grow More

In the midst of a dismal recovery where every job counts, one fact stands out: States that tax less achieve better economic performance. Conventional thinking (at least within government) says that low state taxes are dependent upon having access to unusual revenue sources, but that’s not it. A state could be awash in oil and gas severance taxes and still have a high tax burden if the government will not exercise restraint.

The secret to having low taxes is controlling spending, and that’s exactly what low-tax-burden states do.

States with an income tax spent 42% more per resident in 2011 than the nine states without an income tax. States in the bottom 40 of the Tax Foundation’s Business Tax Climate Index (which assesses business, personal, property and other taxes) spent 40% more per resident. In the American Legislative Exchange Council’s “Rich States, Poor States” Economic Outlook (based on 15 policy variables), the bottom 40 spent 35% more than the top 10 states.

Thoughtful bribes for AP students

Some people at the National Math and Science Initiative think I don’t appreciate them, but that’s not quite right. I enjoy their engaging television ads on great teachers and international competition. Few other private groups have done as much to make high schools more rigorous. They have some of the smartest school reformers I know.

The Dallas-based nonprofit organization has spent nearly $80 million, much of it from the ExxonMobil Foundation, in nine states. The first 136 schools in its program of teacher training, weekend study sessions and student supports have seen the number of passing scores on Advanced Placement math, science and English tests increase 137 percent for all students and 203 percent for African American and Hispanic students in three years. It now has 462 schools, including some in southern Virginia.

My hesitation to embrace its approach has to do with the way I was raised. My parents never paid me for good grades, while students at National Math and Science Initiative schools can get $100 for every AP exam they pass.

The End of the University as We Know It

In fifty years, if not much sooner, half of the roughly 4,500 colleges and universities now operating in the United States will have ceased to exist. The technology driving this change is already at work, and nothing can stop it. The future looks like this: Access to college-level education will be free for everyone; the residential college campus will become largely obsolete; tens of thousands of professors will lose their jobs; the bachelor’s degree will become increasingly irrelevant; and ten years from now Harvard will enroll ten million students.

We’ve all heard plenty about the “college bubble” in recent years. Student loan debt is at an all-time high–an average of more than $23,000 per graduate by some counts–and tuition costs continue to rise at a rate far outpacing inflation, as they have for decades. Credential inflation is devaluing the college degree, making graduate degrees, and the greater debt required to pay for them, increasingly necessary for many people to maintain the standard of living they experienced growing up in their parents’ homes. Students are defaulting on their loans at an unprecedented rate, too, partly a function of an economy short on entry-level professional positions. Yet, as with all bubbles, there’s a persistent public belief in the value of something, and that faith in the college degree has kept demand high.

The figures are alarming, the anecdotes downright depressing. But the real story of the American higher-education bubble has little to do with individual students and their debts or employment problems. The most important part of the college bubble story–the one we will soon be hearing much more about–concerns the impending financial collapse of numerous private colleges and universities and the likely shrinkage of many public ones. And when that bubble bursts, it will end a system of higher education that, for all of its history, has been steeped in a culture of exclusivity. Then we’ll see the birth of something entirely new as we accept one central and unavoidable fact: The college classroom is about to go virtual.

KA-Lite: Khan Academy For The Other 70%

The main focus of this post is KA-Lite: a lightweight web app for hosting Khan Academy content from a local server, without the need for an Internet connection.

“Education is all a matter of building bridges.” – Ralph Ellison

I love Khan Academy. To me, it’s that band that I listened to way before it became popular and everybody else jumped on the bandwagon. I remember discovering Khan way back in December of 2006, when it was just a YouTube channel and I was a wee little high school sophomore struggling to pay attention in my pre-cal class. At the time, I didn’t know how lucky I was to have found those videos. Sal (I call him Sal, because deep down I feel like we’re buddies) always managed to break concepts down in such a concise and visually digestible way. If I didn’t get it the first time, I could play it over and over again until I understood it without the risk of ridicule. It was a relief. It spurred my interest in the material for the first time. And I remember thinking, “Man… I wish Sal could teach all of my classes.”

Fast forward 6 years. The Khan Academy has grown into a full-fledged non-profit organization with funding from entities like Google and The Gates Foundation. It has delivered 217,336,268 lessons to date. Anybody with an Internet connection can type http://www.khanacademy.org into their address bar and have instant access to over 3,600 high-quality lessons on topics ranging from Art History and American Civics to Calculus and Computer Programming. How awesome is that?

Learn About the Educational Reform Plan the School Board Calls ‘Bad for Birmingham’

Parents and school officials concerned with potentially sweeping education reform currently making its way through the Michigan legislature are invited to sound off at a series of informational meetings starting Tuesday across Oakland County.

Dave Randels, assistant director of the office of government relations and pupil services for Oakland Schools, will speak about Gov. Rick Snyder’s education funding proposals from 6:30-8:30 p.m. Tuesday at the Doyle Center in Bloomfield Hills.

“Michigan is embarking on a very radical experiment with our children — one that is untested and untried,” an alert on the Bloomfield Hills Public Schools website read Monday. “We need to come together to learn about this movement and what we can do about it.”

Former Madison Superintendent Dan Nerad is now leading the Birmingham School District.

The Power of Concentration

MEDITATION and mindfulness: the words conjure images of yoga retreats and Buddhist monks. But perhaps they should evoke a very different picture: a man in a deerstalker, puffing away at a curved pipe, Mr. Sherlock Holmes himself. The world’s greatest fictional detective is someone who knows the value of concentration, of “throwing his brain out of action,” as Dr. Watson puts it. He is the quintessential unitasker in a multitasking world.

More often than not, when a new case is presented, Holmes does nothing more than sit back in his leather chair, close his eyes and put together his long-fingered hands in an attitude that begs silence. He may be the most inactive active detective out there. His approach to thought captures the very thing that cognitive psychologists mean when they say mindfulness.

Though the concept originates in ancient Buddhist, Hindu and Chinese traditions, when it comes to experimental psychology, mindfulness is less about spirituality and more about concentration: the ability to quiet your mind, focus your attention on the present, and dismiss any distractions that come your way. The formulation dates from the work of the psychologist Ellen Langer, who demonstrated in the 1970s that mindful thought could lead to improvements on measures of cognitive function and even vital functions in older adults.

Now we’re learning that the benefits may reach further still, and be more attainable, than Professor Langer could have then imagined. Even in small doses, mindfulness can effect impressive changes in how we feel and think — and it does so at a basic neural level.

In reading, the experience counts

It’s “Too Many Tamales” season in selected classrooms. A contemporary classic by Gary Soto, it tells the story of Maria, a girl who loses her mother’s diamond ring as she and her family prepare tamales for their big holiday feast.

I discovered it with my class of first-graders when I taught English-language learners. Unfortunately, only my class experienced “Too Many Tamales.” As the holidays approached, the rest of the school read more “traditional” holiday books. Those students lost out.

My students would have missed out on themes the rest of their grade was involved in had I not insisted that the bilingual students be included in the general curriculum. The “mainstream” teachers thought this was bizarre, as if Hispanic students couldn’t possibly be expected to learn about the same topics as the other first-graders without a mountain of “culturally correct” learning materials.

From Wall Street to College Street: All too often, trustees focus on branding, image, and reputation rather than their academic mission.

The gruesome sexual abuse scandal and cover-up within Penn State’s football program that exploded during fall 2011 rocked the conscience of a community, spawned a raft of criminal indictments of university officials, and ended the careers of the university’s storied football coach Joe Paterno and the university’s long-serving president.

The severity of the depravity at Penn State renders the incident nearly unique. But the response of the university’s leadership–to downplay and cover-up the allegations–is not.

Based on my experience serving as an independent trustee on the Dartmouth Board of Trustees and my academic study of higher education governance, I believe that the cowardly response of Penn State’s leadership is consistent with how many university boards today would respond. I submit that the core principle animating the modern university is a fundamental dishonesty that subverts its core mission. Although the events at Penn State are extreme, they merely magnify the smaller dishonesty and lack of integrity that characterize the modern university.

Via Newark Public Schools: a “data-driven, frank discussion”

Two weeks ago the big New Jersey education story was the CREDO report, which surveyed student outcomes in NJ’s charter schools and found that, while performance in most urban districts was mixed, the results in Newark were remarkable: for every year a Newark student is in a charter schools, she advances seven and a half months in reading and a full year in math compared to a student in a traditional Newark public school.

The CREDO report sparked much debate and some criticism, especially from those feel that Newark’s charters “cream off” kids who are less poor, female, and without special education or English language learning needs. (See Bruce Baker, for example.)

Homework Emancipation Proclamation

The French President’s emancipation proclamation regarding homework may give heart not only to les enfants de la patrie but to the many opponents of homework in this country as well–the parents and the progressive educators who have long insisted that compelling children to draw parallelograms, conjugate irregular verbs, and outline chapters from their textbooks after school hours is (the reasons vary) mindless, unrelated to academic achievement, negatively related to academic achievement, and a major contributor to the great modern evil, stress. M. Hollande, however, is not a progressive educator. He is a socialist. His reason for exercising his powers in this area is to address an inequity. He thinks that homework gives children whose parents are able to help them with it–more educated and affluent parents, presumably–an advantage over children whose parents are not. The President wants to give everyone an equal chance.

Homework is an institution roundly disliked by all who participate in it. Children hate it for healthy and obvious reasons; parents hate it because it makes their children unhappy, but God forbid they should get a check-minus or other less-than-perfect grade on it; and teachers hate it because they have to grade it. Grading homework is teachers’ never-ending homework. Compared to that, Sisyphus lucked out.

Via Laura Waters

The World Bank Brings Nazarbayev University to Kazakhstan

Allen Ruff & Steve Horn, via a kind email:

A number of prestigious, primarily U.S.-based universities are quietly working with the authoritarian regime in Kazakhstan under the dictatorial rule of the country’s “Leader for Life,” Nursultan Nazarbayev.

In a project largely shaped and brokered by the World Bank in 2009 and 2010, the regime sealed deals with some ten major U.S. and British universities and scientific research institutes. They’ve been tasked to design and guide the specialized colleges at the country’s newly constructed showcase university.

As a result, scores of academics have flocked to the resource rich, strategically located country four times the size of Texas. They remain there despite the fact that every major international human rights monitor has cited the Nazarbayev regime for its continuing abuse of civil liberties and basic freedoms.

Kazakhstan now serves as a key hub for the application of the World Bank’s “knowledge bank” agenda, a vivid case study of the far-reaching nature of a corporate – and by extension, imperial – higher education agenda.

What’s an ‘A’ Worth? Many parents pay their kids for top grades. Even when it works, it may not be the smartest investment.

Paying for A’s can actually discourage some kids from working hard. It can create frustration and resentment among kids with siblings. In fact, if the ultimate goal is to encourage the character traits that will help children fulfill their potential throughout life, paying for A’s can fail.

“It comes down to knowing the child and what they are working through,” says Dan Keady, a certified financial planner and director of financial planning at financial-services firm TIAA-CREF.

Facts of Life

Almost half of parents pay kids at least $1 for getting an A, according to a July poll conducted for the American Institute of CPAs, a New York-based professional association. Among those who pay, the average reward for an A is more than $16.

“Paying for grades is one way to prepare them for adult life,” says Mark DiGiovanni, a certified financial planner in Grayson, Ga.

“One of the big facts of adult life is that you do get paid for performing well,” he says. “So this is a way of showing young people that when you do something well, you can get financially rewarded for it. And when you do something poorly, you don’t.”

The Changing Landscape of Education

The Changing Landscape of Education describes the many transitions taking place in the next few years, in response to state and federal mandates for greater accountability, to prepare our students for college and careers, and secure better educational outcomes for schools and students.

Madison schools have increased building security in recent years

Over the past two years the Madison School District has implemented increased safety measures at its schools, including locking school buildings during the day.

As of this school year, all of the district’s buildings are to be locked during the school day, district security coordinator Luis Yudice said. The district works constantly with police to address any potential threats to school safety.

“We have the expectation that if any schools have any hint of threatening behavior, they will direct that to me,” Yudice said. “We try to work at the front end of the problem, before those issues come into the school.”

Yudice addressed questions about building security at Madison schools Friday in the wake of a mass murder at a Connecticut elementary school.

Shift to more nonfiction in schools becoming reality

A broad shift is under way from fiction to nonfiction, propelled by the Common Core English and language arts standards that are being implemented in 46 states and the District of Columbia. It almost certainly will mean fewer classics, more historical documents, fewer personal essays, more analytical writing.

The nonfiction shift is the current center of attention in the changing world of reading instruction.

But it comes in the context of other big shifts: Reading lists that increasingly reflect a diverse population, changes in classroom techniques that promote more student participation, intense focus on how to get more children up to par in reading by third grade and more pressure for schools and teachers to meet accountability standards built largely around reading.

The Common Core standards are intended to provide consistency and quality across the country in what children learn. When it comes to reading, the standards call for fourth-graders to read 50% nonfiction and 50% fiction – and, for 12th-graders, 70% nonfiction and 30% fiction. It’s not possible to compare that to the past, but it clearly moves the needle toward nonfiction.

Why? In general, advocates say, nonfiction gives students better preparation for college and careers by developing such things as analytical skills. And too much of what kids read and write has been too easy and too self-indulgent.

Colleges’ Debt Falls on Students After Construction Binge

A decade-long spending binge to build academic buildings, dormitories and recreational facilities — some of them inordinately lavish to attract students — has left colleges and universities saddled with large amounts of debt. Oftentimes, students are stuck picking up the bill.

Overall debt levels more than doubled from 2000 to 2011 at the more than 500 institutions rated by Moody’s, according to inflation-adjusted data compiled for The New York Times by the credit rating agency. In the same time, the amount of cash, pledged gifts and investments that colleges maintain declined more than 40 percent relative to the amount they owe.

With revenue pinched at institutions big and small, financial experts and college officials are sounding alarms about the consequences of the spending and borrowing. Last month, Harvard University officials warned of “rapid, disorienting change” at colleges and universities.

Edward Tufte: “@EdwardTufte: ET’s Law of University Growth: Bureaucracy doubles every 12 years, while number of students + faculty remains constant.”

In Teacher Pensions, Even the Fixes Are Moving in the Wrong

NCTQ’s new report on the state of state teacher pension plans is well worth your time. If you’re new to the pension issue, it does a great job of breaking down the issues in simple and clear language. If you know your way around defined benefit plans, there’s still lots of good resources on, for example, the number of states that made changes to their pension formulas over the last four years. And, if you only care about a particular state, it has lots of tables where you can find exactly how your home state is doing.

So go read it all and save it as a resource. For this blog, I want to pull out one of its main findings and show why it matters. Since 2009, 13 states have changed their vesting requirements, and 11 of those 13 made this period longer. The vesting period is amount of time a teacher must be employed before becoming eligible for pension benefits. If they meet the minimum vesting requirement, they’re eligible for a pension. If they don’t, they typically can get their own contributions back and some interest on those contributions, but they forfeit the contributions their employer made on their behalf.

Don’t blame teachers for achievement gap

With all due respect to John Legend and Geoff Canada, firing teachers is not the solution to the achievement gap in Madison schools. The two spoke in Madison last week, prompting Friday’s article “Reformers: City schools need institutional change.”

I have been a substitute teacher in many classrooms since 2005 in Madison schools. What do I see?

Teachers who come early and stay late. Teachers who keep a stash of granola bars in their desks for the child who doesn’t make it to school on time for breakfast. Aides who lovingly attend to children with serious special needs.

I see 5-year-olds so out of control they can disrupt a classroom in minutes. Kids who live in their cars.

Madison School District’s Elementary Literacy Program

Madison Superintendent Jane Belmore (2.5MB PDF):

For the past four years, MMSD has been aware that the current implementation of balanced literacy, our core instructional program for literacy at the elementary level, has not resulted in all students making the progress necessary to meet grade level standards. The research shows that three key things are necessary for students to gain proficiency in the common core standards:

- a highly qualified teacher in the classroom

- a strong instructional leader in the school and

- access to an aligned, guaranteed and viable curriculum (Marzano, 2003).

It is clear that MMSD has two out of these three in place: highly qualified teachers and strong instructional leaders. To maintain and develop strong teachers and leaders need well planned, embedded, ongoing professional development. The

School Support Team and Instructional Research Teachers provide us the mechanism for delivering this necessary professional development.

What is needed is a decision about a guaranteed, viable core instructional curriculum that is cohesive across all 32 elementary schools. All student will benefit from consistency across grades levels and schools. Our students from mobile families must have the security and consistency that this core will provide.

60% to 42%: Madison School District’s Reading Recovery Effectiveness Lags “National Average”: Administration seeks to continue its use.

When all third graders read at grade level or beyond by the end of the year, the achievement gap will be closed…and not before.

NJSBA Slams NJ DOE’s Proposal to Augment Superintendent Power

New Jersey School Boards Association has no truck with a new DOE proposal that would let school superintendents unilaterally call for school board meetings. Currently, meetings are held either by preapproved schedules, by board presidents, or through consensus of the board.

Here’s Mike Vrancik, director of NJSBA’s Governmental Relations Department:

Education Bar Graphs of the Year

There is a popular bumper sticker that reads, “If you think education is expensive, try ignorance.” It might surprise you to learn that ignorance is making education more expensive.

The annual Education Next-PEPG Survey, published in Education Next’s Winter issue, unpacks the public’s knowledge of education issues and quantifies just how much ignorance affects one’s opinions on various topics – the most important of which are education spending and teacher pay.

Figure 8 shows what happens to support for increased public school spending after you tell people what we currently spend:

Report: Thousands of public employee retirees draw pension, salary simultaneously

Dee J. Hall, via a kind reader’s email

From substitute teachers to cabinet secretaries, thousands of public employees in Wisconsin who retired in recent years returned to work, allowing them to earn both a paycheck and a state pension, according to a Legislative Audit Bureau report released Friday.

And while many employees and employers like the arrangement, the system can be abused, the report found.

The state lawmaker who blew the whistle on the practice last year, Rep. Steve Nass, R-Whitewater, thinks it’s time for it to be abolished.

“Steve is pretty emphatic — he thinks the report indicates double dipping needs to end,” Nass spokesman Mike Mikalsen said.

But Employee Trust Funds Secretary Robert Conlin said the audit bureau report supports continuation of the practice but with measures to crack down on those who cheat the Wisconsin Retirement System (WRS) by pre-arranging their return to government service. In a letter responding to the audit, Conlin said the Legislature should consider lengthening the mandatory 30-day separation between retirement and re-employment to cut down on abuse.

“The re-hire of WRS annuitants is a lawful practice that, as noted in the audit, appears to serve the needs of retirees and employers,” he said.

From the full report [1MB PDF] Page 35: “We received 1,169 responses to our survey, which is an 82.1 percent response rate. [….] Milwaukee Public Schools and the City of Madison responded, but Madison Metropolitan School District did not, even though we contacted it about responding to the survey.”

Accountability: Report card scores for most Madison schools take small hit

Matthew DeFour, via a kind reader’s email

The report card scores of nearly all Madison schools will be reduced slightly after the district discovered it had reported incorrect student attendance data to the state and revised it.

In most cases the new, lower scores — which the Department of Public Instruction plans to update on its website next week — have no impact on the rating each Madison school receives on the report card. But six schools will be downgraded to a lower category.

Randall and Van Hise elementaries, which were rated in the highest performance category, are now in the second-highest tier. Olson and Chavez elementaries are now in the middle tier. And Mendota and Glendale elementaries are in the second-lowest tier.

The corrections — prompted by a State Journal inquiry — have no immediate practical ramifications, though the implications are significant as state leaders contemplate tying school funding to the report card results.

Adam Gamoran, director of the Wisconsin Center for Education Research, said it’s “extremely important” that the data used to rate schools is accurate. The report cards are part of the state’s new school accountability system, and DPI has proposed directing resources to schools struggling in certain categories.

“The report cards are only as good as the data that goes into them,” he said.

Props to DeFour and the Wisconsin State Journal for digging and pushing.

Related: Madison Mayor Paul Soglin: “We are not interested in the development of new charter schools”.

Where does the Madison School District Get its Numbers from?

Global Academic Standards: How we Outrace the Robots and www.wisconsin2.org.

An Update on Madison’s Use of the MAP (Measures of Academic Progress) Assessment, including individual school reports. Much more on Madison and the MAP Assessment, here.

I strongly support diffused governance of our public schools. One size fits all has outlived its usefulness.

College grads can’t find work

Kenisha Johnson will graduate from the not-for-profit Ottawa University with a bachelor’s degree in human resources in January. She has been trying to find a job in her field for more than a year.

In the process, she has applied for more than 50 jobs. She only received two calls.

To make matters worse, she was laid off from her last job at a collection agency. Ideally, Johnson would like to land a job in her field of study, but that may be unlikely. Only about 20% of recent college grads were lucky enough to find work in their fields.

The problem Johnson and others like her face is that the tight job market has made companies very selective. And while she will soon have a degree in hand, she lacks on-the-job experience.

“It’s discouraging, but right now I’m willing to take any kind of job because I do have bills to pay,” Johnson said.

Bobby Jindal’s alternative education universe

Louisiana Gov. Bobby Jindal, architect of a statewide voucher program that sends public money to religious schools which teach that humans and dinosaurs co-existed, ventured to the Brookings Institution in Washington to present his alternative education universe. Jindal, a rising figure in the Republican Party, spoke for more than an hour defending his voucher program — which was declared unconstitutional by a Lousiana state judge who said it improperly diverts public state and local money to private institutions — without actually mentioning the word “vouchers,” instead using euphemisms such as “scholarships.” Quite a feat.

The Mathematical Hacker

They seem to agree on one thing: from a workaday perspective, math is essentially useless. Lisp programmers (we are told) should be thankful that mathematics was used to work out the Lambda Calculus, but today mathematics is more a form of personal enlightenment than a tool for getting anything done.

This view is mistaken. It has prevailed because it is possible to be a productive and well-compensated programmer — even a first-rate hacker — without any knowledge of science or math. But I think that most programmers who are serious about what they do should know calculus (the real kind), linear algebra, and statistics. The reason has nothing to do with programming per se — compilers, data structures, and all that — but rather the role of programming in the economy.

One way to read the history of business in the twentieth century is a series of transformations whereby industries that “didn’t need math” suddenly found themselves critically depending on it. Statistical quality control reinvented manufacturing; agricultural economics transformed farming; the analysis of variance revolutionized the chemical and pharmaceutical industries; linear programming changed the face of supply-chain management and logistics; and the Black-Scholes equation created a market out of nothing. More recently, “Moneyball” techniques have taken over sports management. There are many other examples.

‘Cal: There’s an App for That!’

There are other topics to catch up on, but by serendipity three similar-themed responses on the UCal Logo Wars arrived at practically the same moment.

One by one, and even more powerfully in combination. they make the excellent point that this is not just about a logo and whether you prefer the “classic stateliness” of the old look or the “bold simplicity” of the new. These writers argue that this seemingly silly controversy in fact raises timely and surprisingly sweeping questions about the future identity, role, and financial underpinnings of great universities. I turn it over to the readers:

Embracing the new. One reader in North Carolina says that the people in charge at UC are merely trying to get ahead of technological and market reality:

Teachers leaning in favor of reforms

Teachers appear to be changing their minds about how they should be hired, assessed, paid and dismissed. This merits attention because we cannot have good schools if teachers are not happy with their compensation and working conditions.

Two new surveys show that teachers, particularly those new to the profession, are friendly to several proposed reforms. The American Federation of Teachers has even endorsed the equivalent of a lawyer’s bar exam for education school graduates.

It’s possible that nothing may come of this. A surge in non-teacher jobs for those with teacher skills or a sharp drop in teacher retirement benefits could leave school districts still scrounging for people with the skill and energy to raise student achievement. But teachers seem to be leaning toward new ways of supporting their work.

The education-policy group Teach Plus looked at teachers with 10 or fewer years of experience compared with those with 11 or more years. The think tank Education Sector compared teachers with fewer than five years experience with those with more than 20 years. Teach Plus used an online poll of 1,015 self-selected teachers, less reliable than the Education Sector’s random sample of 1,100 teachers.

Who Will Hold Colleges Accountable?

LAST month The Chronicle of Higher Education published a damning investigation of college athletes across the nation who were maintaining their eligibility by taking cheap, easy online courses from an obscure junior college.

In just 10 days, academically deficient players could earn three credits and an easy “A” from Western Oklahoma State College for courses like “Microcomputer Applications” (opening folders in Windows) or “Nutrition” (stating whether or not the students used vitamins). The Chronicle quoted one Big Ten academic adviser as saying, “You jump online, finish in a week and half, get your grade posted, and you’re bowl-eligible.”

On the face of it, this is another sad but familiar story of the big-money intercollegiate-athletics complex corrupting the ivory tower. But it also reveals a larger, more pervasive problem: there are no meaningful standards of academic quality in higher education. And the more colleges and universities move their courses online, the more severe the problem gets.

UK Universities recruit 54,000 fewer students

UK universities recruited 54,000 fewer UK and EU students this academic year following the rise in tuition fees, according to the university admissions service, with less prestigious universities suffering the worst of the drop.

The 11 per cent decline in student numbers implies that universities, which had incomes of £27bn last year, could have lost out on £400m of tuition fees, had they been able to sustain the same recruitment levels as last year.

Lifting the fee cap in England from £3,375 to £9,000 was one of the coalition’s most controversial policies, but concerns that poorer students would be particularly deterred have not been realised.

The new figures, released by Ucas, the university courses manager, reveal that the number of UK students from the fifth of households least likely to go to university fell by only 2.4 per cent – roughly in line with demographic change.

Parents, teachers rip Florida’s new education chief

The Florida Department of Education may have said yes to Tony Bennett as its new commissioner of education, but parents and teachers in the community are pushing back with a resounding no.

“We’re in big trouble,” said Lisa Goldman, founder of Testing is Not Teaching, a Palm Beach County school group.

Bennett, Indiana’s outgoing state schools superintendent, was chosen unanimously Wednesday to replace Chancellor of Public Schools Pam Stewart. She served as interim commissioner after Gerard Robinson resigned in August.

Northfield program shrinks Latino achievement gap

When Jhosi Martinez thinks of college, she remembers the words of her father.

“He’s always wanted me to graduate and he’s always wanted me to continue and go to college and become someone else,” the Northfield High School senior said.

Jhosi’s dad never graduated from high school. Neither did her mom nor her older sister. Her family is like that of tens of thousands of Mexicans who have moved to greater Minnesota in search of better opportunities.

Many of those families represent a persistent achievement gap between white students and students of color that Minnesota education have long grappled with.

Global Academic Standards: How we Outrace the Robots

Jobs like that are likely to be well worth having. But who says those robot operators have to be United States-based, just because the machines are? In a world like that, I asked Mr. Schmidt, what are the chances that the United States can expect to have unemployment of 6 percent or even lower?

“I don’t think anyone can say the answer, but we can state the risks,” Mr. Schmidt said. “The way to combat it is education, which has to work for everyone, regardless of race or gender. You’ll have global competition for all kinds of jobs.”

Understanding this, he said, should be America’s “Sputnik moment,” which like that 1957 Russian satellite launch gives the nation a new urgency about education in math and science. “The president could say that in five years he wants the level of analytic education in this country – STEM education in science, technology, engineering and math, or economics and statistics – has to be at a level of the best Asian countries.”

Asian nations, Mr. Schmidt said, are probably going to proceed with their own increases in analytic education. “Employment is going to be a global problem, not a U.S. one,” he said.

I agree with Schmidt on global standards. Learn more about Wisconsin’s challenges at www.wisconsin2.org.

A few background articles on Google Chairman Eric Schmidt: William Gibson:

“I ACTUALLY think most people don’t want Google to answer their questions,” said the search giant’s chief executive, Eric Schmidt, in a recent and controversial interview. “They want Google to tell them what they should be doing next.” Do we really desire Google to tell us what we should be doing next? I believe that we do, though with some rather complicated qualifiers.

Science fiction never imagined Google, but it certainly imagined computers that would advise us what to do. HAL 9000, in “2001: A Space Odyssey,” will forever come to mind, his advice, we assume, eminently reliable — before his malfunction. But HAL was a discrete entity, a genie in a bottle, something we imagined owning or being assigned. Google is a distributed entity, a two-way membrane, a game-changing tool on the order of the equally handy flint hand ax, with which we chop our way through the very densest thickets of information. Google is all of those things, and a very large and powerful corporation to boot.

In the wake of Google’s revelation last week of a concerted, sophisticated cyber attack on many corporate networks, including its own Gmail service, Eric Schmidt’s recent comments about privacy become even more troubling. As you’ll recall, in a December 3 CNBC interview, Schmidt said, “If you have something that you don’t want anyone to know, maybe you shouldn’t be doing it in the first place. But if you really need that kind of privacy, the reality is that search engines – including Google – do retain this information for some time and it’s important, for example, that we are all subject in the United States to the Patriot Act and it is possible that all that information could be made available to the authorities.”