What’s Holding Back American Teenagers? Our high schools are a disaster

High school, where kids socialize, show off their clothes, use their phones–and, oh yeah, go to class.

Every once in a while, education policy squeezes its way onto President Obama’s public agenda, as it did in during last month’s State of the Union address. Lately, two issues have grabbed his (and just about everyone else’s) attention: early-childhood education and access to college. But while these scholastic bookends are important, there is an awful lot of room for improvement between them. American high schools, in particular, are a disaster.

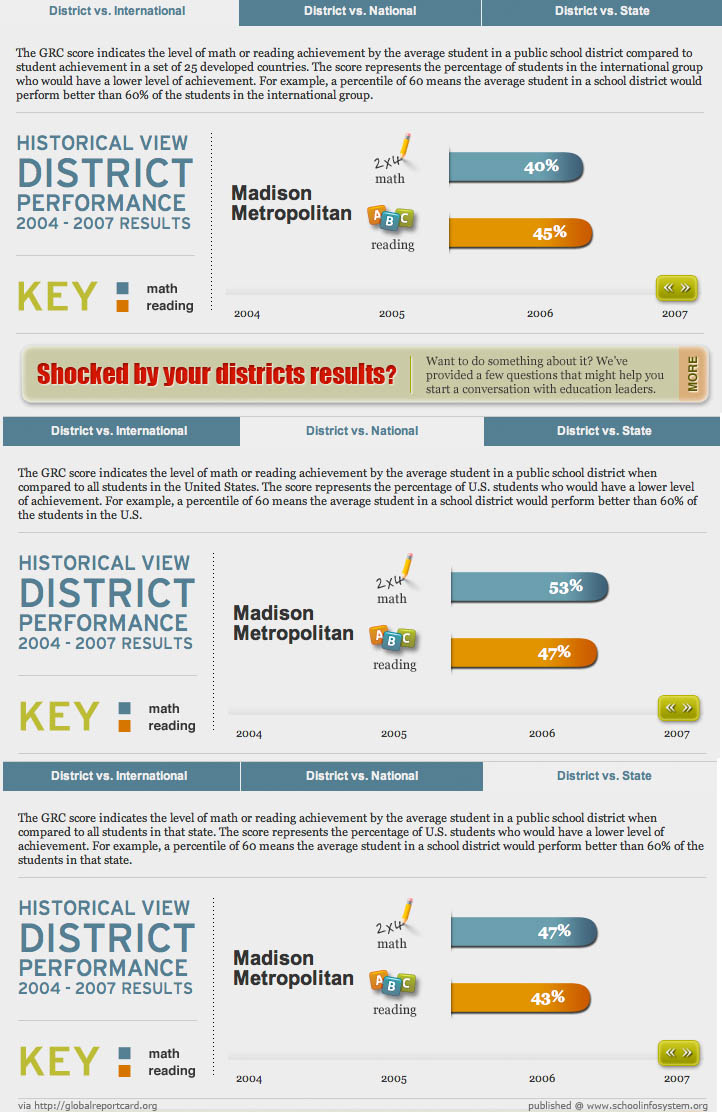

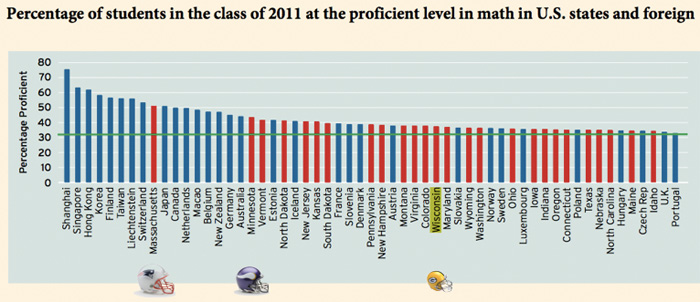

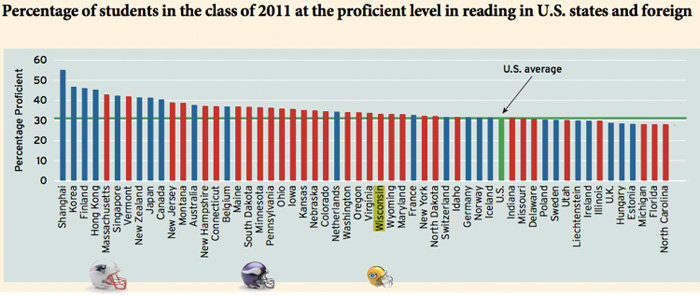

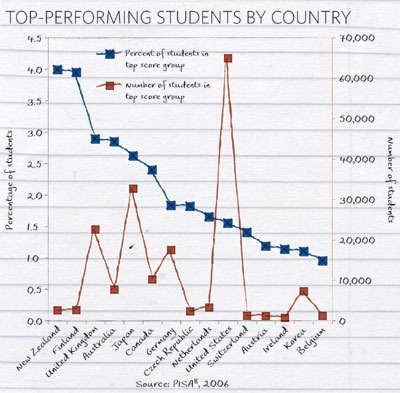

In international assessments, our elementary school students generally score toward the top of the distribution, and our middle school students usually place somewhat above the average. But our high school students score well below the international average, and they fare especially badly in math and science compared with our country’s chief economic rivals.

What’s holding back our teenagers?

One clue comes from a little-known 2003 study based on OECD data that compares the world’s 15-year-olds on two measures of student engagement: participation and “belongingness.” The measure of participation was based on how often students attended school, arrived on time, and showed up for class. The measure of belongingness was based on how much students felt they fit in to the student body, were liked by their schoolmates, and felt that they had friends in school. We might think of the first measure as an index of academic engagement and the second as a measure of social engagement.

On the measure of academic engagement, the U.S. scored only at the international average, and far lower than our chief economic rivals: China, Korea, Japan, and Germany. In these countries, students show up for school and attend their classes more reliably than almost anywhere else in the world. But on the measure of social engagement, the United States topped China, Korea, and Japan.

In America, high school is for socializing. It’s a convenient gathering place, where the really important activities are interrupted by all those annoying classes. For all but the very best American students–the ones in AP classes bound for the nation’s most selective colleges and universities–high school is tedious and unchallenging. Studies that have tracked American adolescents’ moods over the course of the day find that levels of boredom are highest during their time in school.

It’s not just No Child Left Behind or Race to the Top that has failed our adolescents–it’s every single thing we have tried.

One might be tempted to write these findings off as mere confirmation of the well-known fact that adolescents find everything boring. In fact, a huge proportion of the world’s high school students say that school is boring. But American high schools are even more boring than schools in nearly every other country, according to OECD surveys. And surveys of exchange students who have studied in America, as well as surveys of American adolescents who have studied abroad, confirm this. More than half of American high school students who have studied in another country agree that our schools are easier. Objectively, they are probably correct: American high school students spend far less time on schoolwork than their counterparts in the rest of the world.

Trends in achievement within the U.S. reveal just how bad our high schools are relative to our schools for younger students. The National Assessment of Educational Progress, administered by the U.S. Department of Education, routinely tests three age groups: 9-year-olds, 13-year-olds, and 17-year-olds. Over the past 40 years, reading scores rose by 6 percent among 9-year-olds and 3 percent among 13-year-olds. Math scores rose by 11 percent among 9-year-olds and 7 percent among 13-year-olds.

By contrast, high school students haven’t made any progress at all. Reading and math scores have remained flat among 17-year-olds, as have their scores on subject area tests in science, writing, geography, and history. And by absolute, rather than relative, standards, American high school students’ achievement is scandalous.

In other words, over the past 40 years, despite endless debates about curricula, testing, teacher training, teachers’ salaries, and performance standards, and despite billions of dollars invested in school reform, there has been no improvement–none–in the academic proficiency of American high school students.

It’s not just No Child Left Behind or Race to the Top that has failed our adolescents–it’s every single thing we have tried. The list of unsuccessful experiments is long and dispiriting. Charter high schools don’t perform any better than standard public high schools, at least with respect to student achievement. Students whose teachers “teach for America” don’t achieve any more than those whose teachers came out of conventional teacher certification programs. Once one accounts for differences in the family backgrounds of students who attend public and private high schools, there is no advantage to going to private school, either. Vouchers make no difference in student outcomes. No wonder school administrators and teachers from Atlanta to Chicago to my hometown of Philadelphia have been caught fudging data on student performance. It’s the only education strategy that consistently gets results.

The especially poor showing of high schools in America is perplexing. It has nothing to do with high schools having a more ethnically diverse population than elementary schools. In fact, elementary schools are more ethnically diverse than high schools, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics. Nor do high schools have more poor students. Elementary schools in America are more than twice as likely to be classified as “high-poverty” than secondary schools. Salaries are about the same for secondary and elementary school teachers. They have comparable years of education and similar years of experience. Student-teacher ratios are the same in our elementary and high schools. So are the amounts of time that students spend in the classroom. We don’t shortchange high schools financially either; American school districts actually spend a little more per capita on high school students than elementary school students.

Our high school classrooms are not understaffed, underfunded, or underutilized, by international standards. According to a 2013 OECD report, only Luxembourg, Norway, and Switzerland spend more per student. Contrary to widespread belief, American high school teachers’ salaries are comparable to those in most European and Asian countries, as are American class sizes and student-teacher ratios. And American high school students actually spend as many or more hours in the classroom each year than their counterparts in other developed countries.

This underachievement is costly: One-fifth of four-year college entrants and one-half of those entering community college need remedial education, at a cost of $3 billion each year.

The president’s call for expanding access to higher education by making college more affordable, while laudable on the face of it, is not going to solve our problem. The president and his education advisers have misdiagnosed things. The U.S. has one of the highest rates of college entry in the industrialized world. Yet it is tied for last in the rate of college completion. More than one-third of U.S. students who enter a full-time, two-year college program drop out just after one year, as do about one fifth of students who enter a four-year college. In other words, getting our adolescents to go to college isn’t the issue. It’s getting them to graduate.

If this is what we hope to accomplish, we need to rethink high school in America. It is true that providing high-quality preschool to all children is an important component of comprehensive education reform. But we can’t just do this, cross our fingers, and hope for the best. Early intervention is an investment, not an inoculation.

In recent years experts in early-child development have called for programs designed to strengthen children’s “non-cognitive” skills, pointing to research that demonstrates that later scholastic success hinges not only on conventional academic abilities but on capacities like self-control. Research on the determinants of success in adolescence and beyond has come to a similar conclusion: If we want our teenagers to thrive, we need to help them develop the non-cognitive traits it takes to complete a college degree–traits like determination, self-control, and grit. This means classes that really challenge students to work hard–something that fewer than one in six high school students report experiencing, according to Diploma to Nowhere, a 2008 report published by Strong American Schools. Unfortunately, our high schools demand so little of students that these essential capacities aren’t nurtured. As a consequence, many high school graduates, even those who have acquired the necessary academic skills to pursue college coursework, lack the wherewithal to persevere in college. Making college more affordable will not fix this problem, though we should do that too.

The good news is that advances in neuroscience are revealing adolescence to be a second period of heightened brain plasticity, not unlike the first few years of life. Even better, brain regions that are important for the development of essential non-cognitive skills are among the most malleable. And one of the most important contributors to their maturation is pushing individuals beyond their intellectual comfort zones.

It’s time for us to stop squandering this opportunity. Our kids will never rise to the challenge if the challenge doesn’t come.

Laurence Steinberg is a psychology professor at Temple University and author of the forthcoming Age of Opportunity: Revelations from the New Science of Adolescence.

———————————-

“Teach with Examples”

Will Fitzhugh [founder]

The Concord Review [1987]

Ralph Waldo Emerson Prizes [1995]

National Writing Board [1998]

TCR Institute [2002]

730 Boston Post Road, Suite 24

Sudbury, Massachusetts 01776-3371 USA

978-443-0022; 800-331-5007

www.tcr.org; fitzhugh@tcr.org

Varsity Academics®

tcr.org/bookstore

www.tcr.org/blog

>

>